4′ 33″ quickly became John Cage’s most famous composition. It has been hugely influential, a watershed in Western music. But as we have seen, its history was one of hesitancy and delay. Cage declared his serious intention to write a silent piece (Silent prayer) in 1948, and then took four years to get around to actually doing it. Much of the motivation for finally creating the piece came from outside himself: The challenge of Rauschenberg’s white paintings, David Tudor’s encouragement, and the deadline to write it for the Woodstock concert. While 4′ 33″ is seen as a daring creation that changed music, Cage himself can be seen as its somewhat reluctant creator.

Cage may have been slow to take the plunge and create his silent piece, but what did he think about it afterwards? Much has been written about the impact of 4′ 33″ on music and art, but almost nothing about Cage’s own personal relationship to the work. It is easy to see why the histories of 4′ 33″ say so little about how Cage treated the piece after its Woodstock premiere: almost as soon as it was created, he seems to have dropped the subject. Other than a few sound bites about how it was his favorite piece, we do not have many statements by Cage about his most famous work, and certainly nothing extensive or deeply revealing. Leading up to 4′ 33″, John Cage had lots to say about silence and the anechoic chamber experience and unintended sound; afterwards, it seems like everyone else was doing the talking.

Indeed, contrary to what one would expect from the audacity of the piece, it appears that Cage did nothing at all to promote 4′ 33″. For example, he never included it on concert programs. In the descriptive catalog of his music issued by C. F. Peters when they became his publisher in 1962, each work includes an extensive list of performances. The entry for 4′ 33″ lists only three performances over the ten years since its creation. None of these were performances by Cage himself (indeed, I have not found any record of Cage ever having performed the work publicly in a concert setting).

He did not write about the piece, either. Cage’s first book Silence appeared in 1961, containing most of the essays and lectures he had given at that time. 4′ 33″ is mentioned exactly twice in the book, and never by name: it appears in an aside in the introduction to the essay on Robert Rauschenberg, and a description of a “performance” during a walk in the woods is in the humorous piece “Music lovers’ field companion”. That 4′ 33″ is never named in a book titled Silence is a startling omission. Taken together with his reluctance to perform the piece or even put it on his concert programs, an unexpected picture of Cage emerges. Rather than embrace and promote 4′ 33″ as the key piece in his oeuvre, Cage seems to have distanced himself from it.

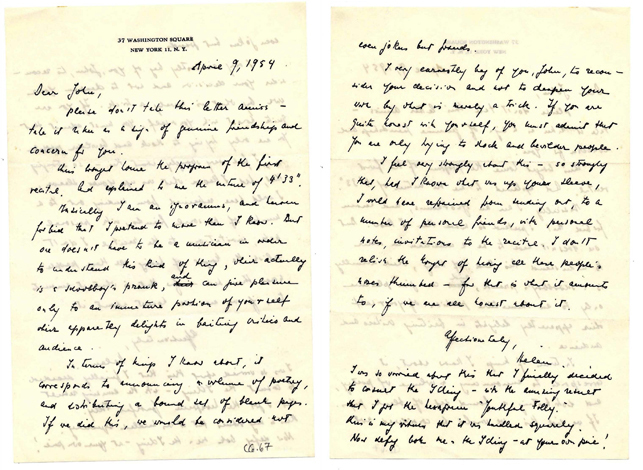

One of the few places in which we encounter Cage discussing 4′ 33″ directly is in a letter to Helen Wolff, the mother of composer Christian Wolff. David Tudor gave the first New York City performance of 4′ 33″ on April 14, 1954 at Carl Fischer Concert Hall. The program also included Music of changes and works by Earle Brown and Christian Wolff. Helen Wolff saw the program in advance and wrote to Cage criticizing him for including a piece of silence. She described it as “a schoolboy’s prank” and advised him to “not cheapen your work by what is merely a trick” that seeks only “to shock and bewilder people.”

In his response, Cage tries to reassure Mrs. Wolff that 4′ 33″ is serious, that it “is not actually silent … it is full of sound, but sounds which I did not think of beforehand.” Beyond that, though, he says nothing more about his intentions for the piece. Instead, he puts the responsibility of meaning on his listeners:

What we hear is determined by our own emptiness, our own receptivity; we receive to the extent we are empty to do so. If one is full or in the course of its performance becomes full of an idea, for example, that this piece is a trick for shock and bewilderment, then it is just that. However, nothing is single or uni-dimensional. This is an action among the ten thousand: it moves in all directions and will be received in unpredictable ways. These will vary from shock and bewilderment to quietness of mind and enlightenment.

If one imagines that I have intended any one of these responses he will have to imagine that I have intended all of them. Something like faith must take over in order that we live affirmatively in the totality we do live in.

Then Cage goes even further, explicitly cutting himself off from 4′ 33″ now that it has moved into the world:

With or without my intention, my art is cheapened and made expensive. That is not my concern. A death to myself takes place in composing and in the event of the movement of this composition in the world, a second death to it as mine must take place. Otherwise I shall be in “fear and trembling”, in a perilous situation of my own imagination.

Cage presents this distancing as a defensive mechanism, a way of protecting himself from the various reactions to the piece. He then uses other third parties for cover: he makes a nod to “oriental thought” and cites the I ching’s response to Wolff’s letter (she herself had consulted the oracle for advice on the matter). Finally, in a postscript, he shrugs off any responsibility for the upcoming performance of 4′ 33″ (even as he denies that he is doing so):

P. S. Incidentally, it was not I but David [Tudor] who decided upon the program. I do not say this to ‘shift the responsibility.’ But that you may be informed of how things actually take place. I composed the piece nearly two years ago. It was performed by David with mixed reactions at Woodstock, N.Y. The piece exists in the repertoire and he chose to program it at the present time. I myself am detached. I am busy with other things, a new composition, concert details of management, this letter, and this springtime.

This letter demonstrates that, as he was personally criticized for creating 4′ 33″, Cage responded by dissociating himself from the piece. There is almost no sign of a composer here at all. He does not describe 4′ 33″ as a work of art that he created or that was motivated by any particular artistic impulse. He spends most of the letter explaining that he cannot control how the piece is received; he says essentially nothing about his own response to its performance. 4′ 33″ appears as a piece with which he has no further relation—”a second death to it as mine” has occurred, and he does not seek to have it performed, to talk about it in any way: “I am busy with other things.” Although he claims that he is not trying to “shift the responsibility”, Cage has in effect abandoned responsibility for the piece. This raises the question: did John Cage regret writing 4′ 33″? By turning his back on it, was he trying in some way to make it just go away?

This may seem like a strange idea at first, especially considering the central place that 4′ 33″ occupies in our understanding of John Cage and his music. But note that for other works in the same period he does not hesitate to discuss his intentions and techniques. His essays and lectures from the 1950s are full of theories and details about Music of changes, Williams mix, Music for piano, and the “Ten Thousand Things” pieces (26′ 1.1499″ for a string player, et al.). He performs these pieces all the time during this period, either himself or in concerts he arranges. He certainly does not shy away from controversy and criticism, making bold statements and taking bold actions. Suggesting that Cage regretted 4′ 33″ is a strange idea, but his reticence to say anything at all about this particular composition—to even acknowledge that it exists unless asked—is itself strange in the context of Cage’s musical life.

§ § §

If Cage saw 4′ 33″ as some kind of mistake, why didn’t he revise it, rewrite it, improve it to correct some of its flaws? In fact, this is exactly what he did—twice. The first revision removed the bars of 4/4 meter, a technical improvement. In 1953, Cage created a new, graphic version of the score for 4′ 33″, consisting of nothing but blank pages. Horizontal space on the page corresponded to time, and vertical lines showed the start and end of movements. The picture below shows the first movement (30”). This correspondence of space with time in a graphic score matches the practice Cage began using in 1953 as he began his Ten thousand things pieces, whose titles also involved lengths of time. This new score is quite beautiful, and it was given to the artist Irwin Kremen as a birthday gift.

The second revision of the score went much further, completely altering the structure of the piece. This version consists simply of text:

I

TACET

II

TACET

III

TACET

That is the score in its entirety. Although the title is given as 4′ 33″, the performance note included with the score indicates that “the title of this work is the total length in minutes and seconds of its performance,” and that “the work may be performed by any instrumentalist or combination of instrumentalists and last any length of time.”

This version of 4′ 33″ is quite different from the other two. Cage has taken it from a fixed score (either metered or graphic) to a more open one, from a performed silence of a particular duration to the generalized concept of three silences. It appears less as a musical composition written by John Cage and more as an invitation for a performer or group of performers to observe silence. The performance note deliberately rewrites the history of the piece, never mentioning that it was conceived as a fixed duration (much less a traditionally-notated piece in 4/4 meter). The note lists the durations that made up the original 4′ 33″ and describes Tudor’s way of performing at the piano, but casts this as just the circumstances of the August 29, 1952 performance. Here, Cage has made a retrospective generalization and expansion of the original, specific work, but the act of this generalization is never acknowledged. This was the version that appeared when Cage’s music was first published in the early 1960s, effectively hiding the origins of the piece from those who purchased it from C. F. Peters.

This history of the score for 4′ 33″ is unusual and underscores Cage’s deliberate rupture of his connection to the piece. There is no other mature work that I am aware of that Cage revised, and certainly not one that is as significantly reworked as 4′ 33″. This is the composer who rejected the idea of a “mistake”, saying that “once anything happens it authentically is.” In that context, what does the radical revision of the score mean? Cage created a silent score in 1952, but when it came time to publish this “authentic” fact, he created something completely different, including misleading comments that erased his own past choices about the durations of the movements and even the title of the work. There clearly was something about 4′ 33″ that Cage felt wasn’t quite right, and he went to some lengths to make the original, flawed version go away.

§ § §

It may seem bizarre to suggest that Cage regretted—if not actually rejected—the composition of 4′ 33″. What about all those times he called it his favorite piece? Didn’t he refer to it as the touchstone of all his work? Looking at his statements, there is an important distinction to be made: while he speaks about the importance of “my silent piece,” he almost never speaks about 4′ 33″, the composition that he wrote using charts of silences and which David Tudor played at Woodstock and Fisher Hall. I would propose that there is a very real difference here. “The silent piece” as Cage describes it is a personal experience of silence, of emptiness, closer in intent and importance to the way that Silent prayer is described in “A composer’s confessions.” 4′ 33″ is a specific composition, a thing measured and made by Cage using musical score paper, a concert work put on programs and performed on stage by professional performers for audiences. As I have suggested elsewhere, such a material manifestation of silence cannot really embody the deep experience of emptiness that Cage means when he refers to “the silent piece.” When I say that Cage regretted 4′ 33″, I mean that I believe he saw this disconnect between intent and expression. When the energetic and often negative response came after the work was performed, he knew that he had made a mistake.

This distinction between “the silent piece” and 4′ 33″, along with Cage’s embrace of one and rejection of the other, is made clear in an interview with Richard Kostelanetz from 1966 (emphasis mine):

[Cage:] If you want to know the truth of the matter, the music I prefer, even to my own or anybody else’s, is what we are hearing if we are just quiet. And now we come back to my silent piece. I really prefer that to anything else, but I don’t think of it as “my piece.”

[Kostelanetz:] Isn’t it an extension of your 4′ 33″

[Cage:] No, it’s my experience now. I wrote that piece in 1952. This is now 1966. I don’t need that piece today.

[Kostelanetz:] In a sense, though, you are fortunate enough to hear it all the time.

[Cage:] True, now it no longer has three parts, as it did originally. You remember it has three movements, which were determined by chance operations Now I don’t have to use those chance operations, for we don’t have to think in terms of movements any more.

With his revisions of the work, Cage clearly realized that the form of 4′ 33″ as originally composed didn’t match his conception of silence: it didn’t make the selfless space of unintended sounds apparent. In order to do that, he’d need to recast the piece in a completely different form, something that couldn’t get confused with concert music, that didn’t focus on the image of a performer rendering a score, that highlighted the unintended sounds, great and small, that are under the surface of our everyday life. In 1962 he wrote exactly such a piece and called it 4′ 33″ No. 2.

Next in this series: The silent piece, rebooted: 0′ 00″

Home page for the entire series: John Cage’s silent piece(s)

Notes & asides

The picture of Helen Wolff’s letter at the head is taken from the Museum of Modern Art’s site related to the exhibit Silence Is Not What It Used to Be. Cage’s response is published in The selected letters of John Cage, edited by Laura Kuhn (Wesleyan, 2016). The Kostelanetz interview in which Cage says “I don’t need that piece today” appears in John Cage, edited by Richard Kostelanetz (Praeger, 1970).

The text-only version of the score of 4′ 33″ was the first to be published, although the exact date of that publication is unclear (it could have been as early as 1953, although I doubt it). This was the only version that was known of until 1967, when the Kremen graphic score was published in Source issue #2. That beautiful score and accompanying essay has been republished in Source: Music of the Avant-garde, 1966–1973, edited by Larry Austin and Douglas Kahn (University of California Press, 2011).

Liz Kotz (in her Words to be looked at) and Kyle Gann (in No such thing as silence) both have detailed histories of the various scores of 4′ 33″, and I am indebted to them both.

Pingback: John Cage's silent piece(s): The composition of 4' 33" - James Pritchett

Very thought-provoking. The connection to the “Frankenstein”characterization of the Music of Changes makes a lot of sense, and I think I had read that he had a similar reservation about Williams Mix. I’ve been thinking recently about how Music for Piano, the project which is taken up shortly after, is so massive: Cage stuck with that mode of composition (imperfections in the manuscript paper) for such a long time compared with others he used at other times. Your essay implicitly connects some of the dots here–perhaps Cage viewed all of those early chance pieces as Frankenstein monsters to some extent, and on the other hand felt like the Music for Piano compositional method was a more organic, human, non-Frankensteinian breakthrough. I feel an intuitive kinship between the revised scores for 4’33” and Music for Piano, especially the one he gave to Kremen. The “Tacet” version feels connected to Fluxus scores by virtue of its being a text piece, and now that I think of it definitely points towards 0’00”. Thanks for stimulating so much thought!

Pingback: John Cage's silent piece(s): One silent piece or four? - James Pritchett

Thanks for this wonderful piece of writing.

It strikes me that the three notations actually reflect three different understandings of time structure.

The first is metrical, the second is “time observed” through a stop watch, the third is ‘no time’. So the metrical understanding of time structure used to compose the piece vanishes with the second notation and the performer disappears with the third. And that whole trajectory has been largely invisible in its reception until the publication of A Composer’s Confession.

This might explain the slightly testy tone of Tudor’s account describing the origins of the piece in an interview (from an anthology of interviews by a British journalist whose name I cannot recall.)

whoops, didn’t sign in

Pingback: John Cage's silent piece(s): One silent piece or four? - James Pritchett