[This is part of the series Opening the door into emptiness]

In the mid-1940s John Cage was searching for a deeper meaning to his life in music, something beyond his personal ambition and need for self-expression. By 1950 he had arrived at a style that celebrated emptiness. Paradoxically, by letting go of any strong self-expression, Cage discovered a truer musical voice. He saw that it was the discipline of systematic approaches that created his own “poetry of things,” a music where sounds could “speak their own silent and expressive language” (as R. H. Blyth described haiku).

His next major work, the Concerto for prepared piano and chamber orchestra, was to explicitly present this release from self-expression. As Cage described it later:

I made it into a drama between the piano, which remains romantic, expressive, and the orchestra, which itself follows the principles of oriental philosophy. And the third movement signifies the coming together of things which were opposed to one another in the first movement.

The prepared piano, so closely identified with his music of the 1940s, would play the part of John Cage, the seeker of wisdom. The orchestra would represent the bright, clear, empty space to which he was turning. The piano would make the journey from expression to non-expression, joining the orchestra in pure presence by the ending.

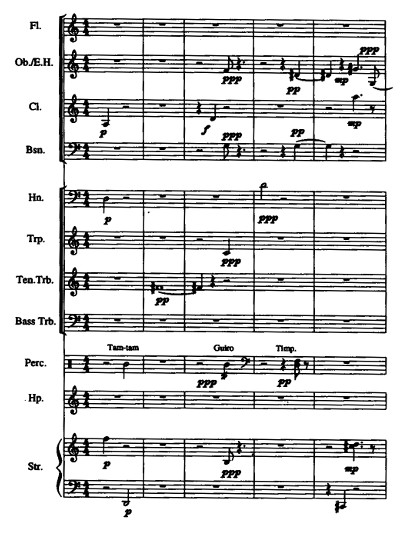

His work on the string quartet had shown him the power of applying systematic control to his musical materials. In the orchestral music of the concerto, Cage pushed this approach further. In the first movement, for the orchestra music, he again started from a fixed collection of sounds, each given a specific orchestration. To further systematize their use, Cage arranged these sounds into a 16-by-14 grid. To determine the order of sounds within each phrase of the rhythmic structure, he made specific geometrical moves on this grid. Finally, he composed the rhythms of these sounds to fit within the phrase. Following his program of expression versus non-expression, the prepared piano music in this first movement follows no system and uses no chart. The two characters in this concerto-drama are quite distinct, and Cage has them play in alternation throughout, never together.

The second movement represented a step towards unity between piano and orchestra. Cage created a chart of sounds for the prepared piano and used the same compositional technique for both piano and orchestra parts. They still speak antiphonally, but they follow the same set of moves on the chart. These moves were in the form of concentric circles drawn on the charts, starting with the largest and moving to the center. This suited the program of the concerto, and Cage described this second movement as being like the way “a disciple follows his master, in a sort of antiphony, then comes to join the latter in his impersonality.”

The chart technique created a musical style that was different from the string quartet—quite different from all of Cage’s prior work, in fact. The continuity of the quartet was driven by a melodic line. The simplicity of this line and the openness of the harmonies gave the music a gentleness and an ancient feeling. One can connect its sound to that of the music of Erik Satie. The continuity of the concerto, on the other hand, is largely the result of arbitrary moves on the chart, and the sound materials themselves are more fragmentary and dissonant. The music sounds much more in line with the kind of Webern-influenced work that Cage would have heard during his recent trip to Europe. Listening to Cage’s concerto and Webern’s symphony in sequence, one can make the connection between these sound worlds.

With the concerto, Cage brought a systematic treatment to three of the four elements of music: structure, material, and now the note-to-note method as well. He was aware that this was quieting his voice even further, producing continuities of his sounds that were not driven by any kind of personal expression. “All this brings me closer to a ‘chance’ or if you like to an un-aesthetic choice,” he wrote to Boulez at the time.

Cage and Boulez were in the middle of an energetic correspondence in 1950. Their shared interest in systematic procedures no doubt encouraged Cage in his path of discovery. Now Cage was poised to compose the last movement of the concerto, the music that would fully integrate the prepared piano and orchestra. Cage did not describe his plan for this in his letter to Boulez, so we can only speculate on what his early thoughts were. Perhaps he would combine the piano and orchestra into a single chart? Perhaps he considered including longer silences? Just the right technique might have been unclear to Cage at the time, but a different engagement with a different composer would change all of that. John Cage invited Morton Feldman over for dinner, and his concerto and his life changed as a result.

Read the next post in this series: 8 — Letting go completely

Sources & asides

For fuller descriptions of the methods used to compose the first two movements of the concerto, see the author’s The music of John Cage, pp. 60-66, and “From choice to chance: John Cage’s Concerto for prepared piano”, Perspectives of new music 26/1 (Winter 1988), pp. 50-81. Cage’s comments about the program of the concerto come in an interview with Daniel Charles, published in For the birds (Marion Boyars, 1981), pp. 41 & 104. Cage describes his concerto to Pierre Boulez in a letter on 18 December 1950, translated in The Boulez-Cage correspondence (Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 78.

Last year, I blogged about the concerto and Cage’s response to its disastrous premiere.