[This is part of the series Opening the door into emptiness]

During his stay in Paris in 1949, John Cage met Pierre Boulez. Cage was energized by the younger composer’s zeal and ferocious music. They carried on a lively correspondence over the next few years, and there is no doubt that this exchange with Boulez was a factor in Cage’s musical path at the start of the 1950s. But however similar their interests may have seemed at that time, Cage and Boulez were on fundamentally different paths, and their brief period of shared enthusiasm was doomed to break up fairly quickly. There was another younger composer from this period who shaped Cage’s music much more strongly, and with whom he had a much deeper and longer-lasting friendship: Morton Feldman.

Feldman and Cage met in January of 1950. Feldman had just turned 24 years old and was composing music he later described as “vaguely modernistic,” in “the sound world of a Schoenberg or a Berg.” Like both Cage and Boulez, he was excited about the work of Webern, and he attended a performance of the Webern Symphony by the New York Philharmonic. Having heard what he came to hear, Feldman left the concert after the Webern and ran into Cage, who had done the same. Feldman followed up with a visit to Cage’s beautiful, austere apartment on the Lower East Side, and soon moved into another apartment in the same building.

Feldman and Cage found that they had much in common, and they moved through the stimulating New York art world together. They spent long hours together discussing their music and hanging out at the Cedar Bar to talk some more with artists there. “I can say without exaggeration that we did this every day for five years of our lives,” Feldman recalled. As implied by their having been introduced through a mutual admiration of Webern, both composers were exploring a sparse world where sounds were heard in crystal clarity against a field of silence. Boulez and Cage had shared an interest in systems and discipline; Feldman instead was closer to Cage spiritually, believing in the significance of sound in itself, its inherent mystery. He wanted to move beyond compositional rhetoric and to find ways to project sounds directly into time. One can easily imagine Cage wanting to discuss such matters for hours on end.

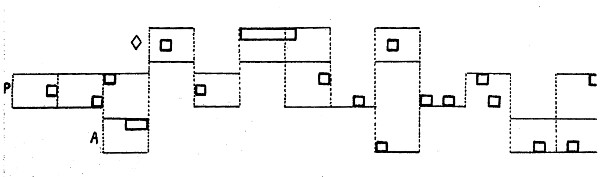

One evening in late 1950, possibly after just such a conversation, Cage went into his kitchen to cook some wild rice; Feldman sat in the next room and sketched on graph paper while he waited for dinner. What Feldman created was the graph notation of his first Projection. When Cage emerged from the kitchen, Feldman showed him empty rectangular spaces representing sounds to be produced in general registers (high, medium, low). None of the specific pitches or rhythms were notated at all. It was the graph notation that would become his first Projection for solo cello.

Seeing Feldman’s empty squares, Cage was astonished. His musical and spiritual journey seemed to lead to this very moment. He had been unsatisfied with his life as an ambitious composer, and this unsatisfactoriness had led him to ask why he wrote music at all. He had seen that the true purpose of music must be to connect the individual to the eternal, and that in order to do this, he had to let go of ambition, loosen his ego’s hold on his music. As he worked through his compositional approach, he had seen that it was systematic procedures that could produce a space within which his musical continuities could take on more freedom, producing moments of pure sonic experience that touched something larger. And now Feldman demonstrated at one stroke the extent to which freedom was possible: one need only step out of the way and let the sounds emerge from the silence of their own accord. With regards to creating musical continuity, there was literally nothing that needed to be done. Feldman’s graph notation was radical for Cage not only because it showed that relinquishment of control could be taken further—much further—than he himself had done so far, but also because of the way in which Feldman did it: casually, effortlessly, completely, in an idle moment while waiting for dinner.

Feldman’s Projection was a revelation for Cage, the opening of a door to an entirely new world, “not just the musical world outside of you”, as he later described it, “but the musical world inside of you.” He now saw how to make the last movement of his piano concerto, how to bring piano and orchestra together and have them both follow the silent voice of chance. Feldman never saw the graph notation as embracing chance or randomness, but Cage saw it in the context of his own journey, and chance music was the path it pointed out to him. Spiritually, he saw Feldman’s remarkable notation as the discovery of a hidden wisdom achieved through a brave act of self-negation. Feldman, of course, saw this differently as well. When Cage excitedly described Feldman as “heroic” to the Artists’ Club in January of 1951, Feldman’s response was “that’s not me, that’s John.”

Read the next post in this series: 9 — Opening up another world

Sources & asides

Morton Feldman recounted his early experiences with Cage in liner notes for a 1963 album on Time Records, republished as “Liner notes” in Give my regards to Eighth Street: Collected writings of Morton Feldman (B. H. Friedman, editor, Exact Change, 2000), pp. 3–7; and in the title essay from that same collection (originally published in in 1968), pp. 93–101. Feldman also reminisces about this time in an interview with Alan Beckett of the International Times in 1966, reprinted in Morton Feldman says: Selected interviews and lectures 1954–1987 (Chris Villars, ed., Hyphen Press, 2006), pp. 30–33. The story of the wild rice appears in Jan Williams, “An interview with Morton Feldman”, originally in Percussive notes, September 1983, republished in Morton Feldman says, p. 153.

John Cage describes Feldman as having “discovered a world” in conversation with Feldman in “Radio happening I”, recorded at WBAI, New York, 9 July 1966. Transcript published in John Cage and Morton Feldman, Radio happenings I-V (Cologne: MusikTexte, 1993), p. 17. Cage notes the difference between his own characterization of Feldman’s work and Feldman’s self-view in the introduction to “Lecture on Something”, Silence, p. 128.