The above two-measure, two-chord pattern appears repeatedly towards the end of Palais de mari. While learning this part of the piece, I quickly noticed that it felt like a long, conscious breath. It always appears exactly as above: two whole notes, repeated once. In my score, I pencilled in the words “IN – OUT” above each occurrence of this pattern, and when I play it, I bring my attention to my breath.

The above two-measure, two-chord pattern appears repeatedly towards the end of Palais de mari. While learning this part of the piece, I quickly noticed that it felt like a long, conscious breath. It always appears exactly as above: two whole notes, repeated once. In my score, I pencilled in the words “IN – OUT” above each occurrence of this pattern, and when I play it, I bring my attention to my breath.

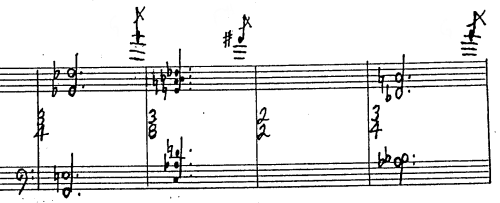

To me, there is a dark, ominous quality about this music. It appears as an interruption of the music around it: the grace-note figures I showed in my last post on meter and counting. Those figures are light, open, bright, simple. There is a sweetness and poignancy to the way that they proceed, sometimes in two-note phrases, sometimes strung along into longer continuities. They are evolving and even meandering at times; Feldman tries out many different combinations and sequences. These are then interrupted periodically by the breathing sequence above: middle-register, chromatic, dense, going nowhere. The pattern repeats seven times without alteration in the last half of the piece.

As I hear this more and more as a dark, second character interrupting the other, brighter flow, I’ve been using a little rubato here, adding a tiny pause before and after the IN-OUT to set it off a little bit. Actually, I should say that it’s not that the breathing interrupts the flow of the other music, but rather it sounds as if it is something that has been there all along, but it only comes to the fore at times. It is like our awareness of our breathing bodies: they are there all the time, but we only notice them occasionally when we aren’t too busy thinking about other things.

But let me get to more “purely musical” matters: where do these chords come from? I traced the sequence backwards. The first appearance of this particular repeated pair is midway on page 5 of the score. From here to the end (p. 8 ) the pattern appears a total of seven times, exactly the same each time, and once this pattern appears, neither of its chords appears in any other context. The pattern is “fixed” in this state from p. 5 onwards.

The first chord appears by itself earlier, however. It first occurs by itself, followed by a high grace note and surrounded by two long measures of silence, at the bottom of page 4. It appears again in that form on p. 5, just before the two-chord repeated version shows up, again surrounded by silence. In both cases, the context is a series of long chords surrounded by silences, which gives the effect of looking for a particular sonority, trying out the possibilities.

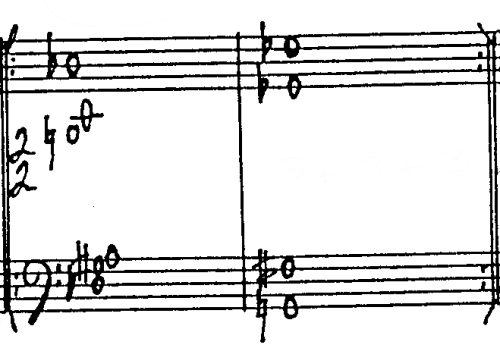

I discovered that the second chord went much further back in the piece. It doesn’t appear in that exact form until it becomes part of the settled, repeated breathing pattern, but similar sonorities appear all the way back on page 1. When I looked back at that first page, it all started to make some sense to me. The opening of the piece is all open, bright intervals: single notes in each hand. This is interrupted by chords with following grace notes that I always felt sounded darker, from a different space. Looking at these now, I see that it’s the forerunner of the breathing pattern above:

The notes in the chords aren’t the same, but the registers are and, more importantly, the weight and feel of them are quite similar. They appear as a shadow character in the music through the entire first half of the piece, then step back to make way for the breathing pair at the end. These chords aren’t “fixed” yet, so they shift around a good deal from one appearance to another, but the oscillation between d-flat and a-natural is clear, an ancestor to the d-flat/b-flat that finally arrives at the end. But without the close proximity and rhythmic regularity of the ending, we don’t hear these as a pair. It’s only when they achieve that regular oscillation that it sounds like breathing.

Tracing this history was really illuminating for me. Listening to pieces like Palais de mari, I’ve often had the experience of motives, patterns, or ideas suddenly appearing very clearly and in some kind of stable form, but having the feeling that they had shown up earlier and I hadn’t really noticed them. I think that this may be a typical process in later Feldman: sounds coming together to achieve a fixed, clear pattern that may persist for awhile. In this case, the clarity happens at the end and passes away with the end of the piece itself. I wonder if, in larger pieces, this kind of thing comes and goes throughout?