In a recent lecture on Feldman’s music, Bunita Marcus said that Feldman was ”playing with memory and the evolution of memory.” I’ve noted on many occasions (including occasionally in this blog) that the continuity of Feldman’s music is like the continuity of thought, so the connection to memory seems very powerful to me.

The next part of For Bunita Marcus (pages 16-19) is devoted to this “playing with memory”. These four pages are filled with music we’ve already heard before, but reconfigured in ways that affect our connection of the current events to the past ones. Actually, I first noted this on pages 5-6. Here Feldman repeats the seven phrases of the opening page of the piece, but in a different order (4, 3, 6, 2, 1, 7), and with very slight modifications: a missing note here, a register change there. It actually sounds like Feldman was playing these phrases from memory here, and the anomalies are places he didn’t quite remember it correctly. I have no idea whether this is what happened; that’s just the way it sounds.

It’s worth noting that, in general, this music encourages tricks of memory. The chromatic noodling of these first seven pages is very labyrinthine: it’s disorienting if you’re trying to keep track of what’s happened before. Had I not been reading this from the score and playing it over and over, I might not have noticed the repetitions on pages 5-6 at all, although the repeat of the opening phrase is noticeable, since we tend to remember beginnings well. I hear the overall progression of adding more tones to the mix, but that’s really all: a vague notion that we’re moving somewhere, but no clear point-to-point motion, no obvious reference points. When we hit those repeated phrases on page 5, we might ask ourselves, have we been here before? Or we might just have an unrecognized sense of familiar terrain.

All four of the pages 16-19 are devoted to this kind of deliberate reconfiguration of memory. Each separate page takes as its source an earlier page and applies a different method to transform that source page. Some of these are done quite systematically, some are not. Here are the geeky details:

- Page 16. The music on this page is identical to that on page 11, but reordered by system. The five systems of page 11 are presented in almost-reverse order: 5-4-3-1-2. And the nine measures within each system appear in reverse order. The music within each measure is unchanged.

- Page 17. The music here comes from page 7. That page consists of a number of phrases set off from each other with silent measures. On page 17, Feldman for the most part presents the same phrases in a different order. One phrase (the sixth one on page 7) is missing, and another (the eighth) is repeated in its place. And the final phrase (which appears at the end of both pages) is varied slightly on page 17.

- Page 18. The music here is derived from page 13. The connections are much looser, although almost every measure on page 18 can be identified in page 13. In this case, rather than rearrange the systems, the individual measures of page 13 are reordered. There is a rough overall movement backwards through the music of page 13, although this is not followed systematically. Most of the measures are exactly the same, although some modify the original slightly through octave displacements and the chromatic inflection of a note here or there. Four measures are similar to music found on page 13 but do not actually appear there.

- Page 19. This follows a similar process as page 18—reordering the individual measures of a page—but using the music of page 18 itself as the source, so that we are now hearing a twice-shuffled version of page 13. In addition, all measures are transposed up a semitone. For the most part only measures from the first three systems of page 18 are used—the interlocking figures, not the chromatic lines of the last two systems. There are a handful of measures with new music as well, but mostly it is just page 18 cut up and transposed.

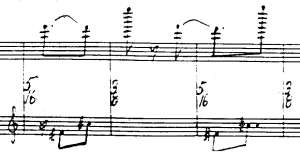

The last few bars of page 19 introduces an entirely new image that clearly heralds a change:

So in these four pages, Feldman has taken music from various earlier points in the piece and rearranged it at the measure-to-measure level, while keeping the content of the measures themselves relatively constant. The shape of the phrases and figures are unchanged and hence recognized as related to our past experience, but the configurations are new, which challenges our memories. The pages all feature similar music—mostly the interlocking motives that first appeared at page 11—which makes this section seem even more labyrinthine. Of course those interlocking motives all have similar profiles in the first place, but there are some specific, recognizable moments that tickle our memory when they appear again here. And appearing as they do in similar, but altered surroundings gives us the feeling of déjà vu: we know that we’ve been here before, but we are uncertain exactly how it happened the first time. And it’s not just the ordering of these things in time that has been played with. Page 19’s transposition up a semitone gives the music of page 18 a different color altogether, even as the rhythms, intervals, and registers remain the same.

So in these four pages, Feldman has taken music from various earlier points in the piece and rearranged it at the measure-to-measure level, while keeping the content of the measures themselves relatively constant. The shape of the phrases and figures are unchanged and hence recognized as related to our past experience, but the configurations are new, which challenges our memories. The pages all feature similar music—mostly the interlocking motives that first appeared at page 11—which makes this section seem even more labyrinthine. Of course those interlocking motives all have similar profiles in the first place, but there are some specific, recognizable moments that tickle our memory when they appear again here. And appearing as they do in similar, but altered surroundings gives us the feeling of déjà vu: we know that we’ve been here before, but we are uncertain exactly how it happened the first time. And it’s not just the ordering of these things in time that has been played with. Page 19’s transposition up a semitone gives the music of page 18 a different color altogether, even as the rhythms, intervals, and registers remain the same.

I was well aware of this kind of memory effect in Feldman’s music, but I had never realized how systematic the approach was until I started working through this score. One way to look at this is that Feldman is deliberately confusing and disorienting the listener. We’ve entered a part of the piece where he wants to have us revisit music that we’ve encountered before, but he wants to change our felt sense of this music by changing the context in these methodical ways. It’s not just a matter of “developing themes” as it is producing a particular effect of memory, a pattern of simultaneous recognition and uncertainty.

Another way of looking at this is that what we are witnessing here is Feldman’s own thought itself. Perhaps not confusion or uncertainty, but exploration and play. Feldman is at a point where he wants to revisit music that’s occurred before, but to see what other possibilities for combinations and sequences there are. The various ways of rearranging measures of music that we find in pages 16-19 are means, systematic to varying degrees, of rediscovering the material. Viewed this way, Feldman’s motivation is strikingly similar to Cage’s in his adoption of chance operations in the 1950s. I have always felt that Feldman was the man behind Cage’s taking the leap into chance, and so this connection intrigues me.

Finally, yet another way to look at it, if you want to further the analogy of continuity of thought, is to view this passage as being like the experience one has of this music when one is away from it, the different images and figures tumbling around in one’s mind. Different flashes of beauty stand out for us, and every time we let these measures sift through our memory, we pick out different ones as our favorites—or at least the ones that stick in our minds today.