I’ve been listening to a lot of Morton Feldman’s earlier music from the 1950s lately. When studying a composer, I like to work chronologically sometimes, especially with their writings about music, but also with the music itself. It helps to develop the story line of their work for me: how they got from point A to point B.

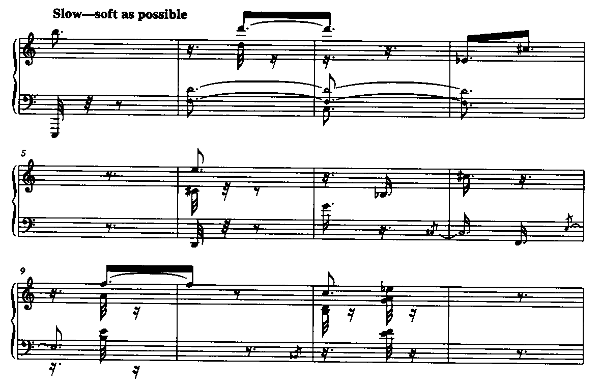

With Feldman, this process pointed out a really sharp change in the work in 1957, with his Piece for 4 pianos. The difference is quite apparent from the scores. Here’s the opening of Piano piece 1956B:

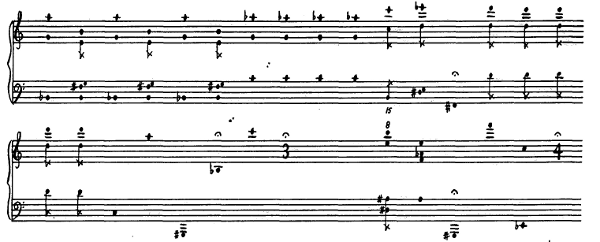

And here’s the opening of Piece for 4 pianos, written just a little while after:

The two sounds are quite dissimilar. In the earlier piece the sounds are separated from one another, bubbling up in the silence. There are subtle rhythmic distinctions made, and the events have different profiles. In Piece for 4 pianos, almost all of this is gone. The sound is a continuous reverberation of pianos, and the rhythms are completely flattened to a simple pulsing. One might be tempted to point to the repetitions at the start of the piece as a major change, but I find them incidental to the bigger differences in sound.

There doesn’t seem to be much in the work of the mid-1950s to suggest that this new sound was coming down the pike. There are a few isolated pieces that have something in common, most notably Piano piece 1952 and Intermission 6 (1953). But these are not exactly the same, and they are isolated experiments. In 1957 with Piece for 4 pianos, Feldman’s music made a real shift. The pieces following belong in this same sound world, leading to the Durations series of 1960-61. I’m not familiar with all of the works of the 1960s, but it appears that the world of Piano piece 1956B disappeared completely in 1957.

What ties these worlds together is something that I think gets at the heart of Feldman’s work: a direct engagement with sound. In both of these pieces we are hearing Feldman at the piano, working with sound. What we hear is Feldman listening. What has changed is the type of engagement. In the early 1950s, it was a way of working within silence: applying sound onto silence, or perhaps coaxing sound out of it. We are very aware in a work like Piano piece 1956B of each sound being carefully made with its own character, like a brushstroke on blank canvas. In Piece for 4 pianos, Feldman created a sound world, a sound that is like a plastic material that can be shaped and worked. Once he’s established that sound, he’s keeping it going, bringing it to rest here (through those repeated sounds), pushing it forward there. But in both cases we’re keenly aware of his attention, his engagement.