I’ve been thinking about David Tudor and John Cage a good deal lately, following some hunches to develop what I think is a useful way of looking at their history in the 1960s. I don’t know that I’m completely convinced of my story line here, but it’s intriguing.

Knowing my interest in both John Cage and Morton Feldman, Laura Kuhn at the John Cage Trust sent me a copy of a recording she recently received of Cage and Feldman teaching a seminar at the New York Studio School in the 1960s (the recording probably dates from sometime in early 1968). One thing that caught my attention was this story that Cage tells about the genesis of his piece Music for amplified toy pianos (1960):

I remember in this connection a performance at Wesleyan University of a piece that I’d written for amplified toy piano. I had previously written a suite for toy piano (unamplified). Then, in a drug store in the course of one of our tours, David Tudor noticed these little toy pianos that were just like grand pianos, and the lid would come up, and there were these bars and so forth. The whole thing was suitable for amplification by means of contact microphones. And he assembled all sorts of small objects to set the various parts in vibration, like nail files and toothbrushes, all manner of things. It was an extremely interesting piece. When I heard it, I was absolutely delighted. And then one of the students at Wesleyan came up and said “Couldn’t you have made it more effective?”

What struck me about this is the portrayal of Tudor as the motivating force behind the piece. Of course Cage talked often about the importance of Tudor for his music (especially in the 1950s), but this story suggests something more. Tudor appears here as the one who discovered the instruments and invented the way of playing them. In effect, David Tudor created the sound world of Music for amplified toy pianos. It’s not clear, but it reads to me that Cage composed the piece after Tudor did this. There really wasn’t that much to do: Cage adapted some of his graphic notation methods to create a tool for randomly projecting these sounds into time.

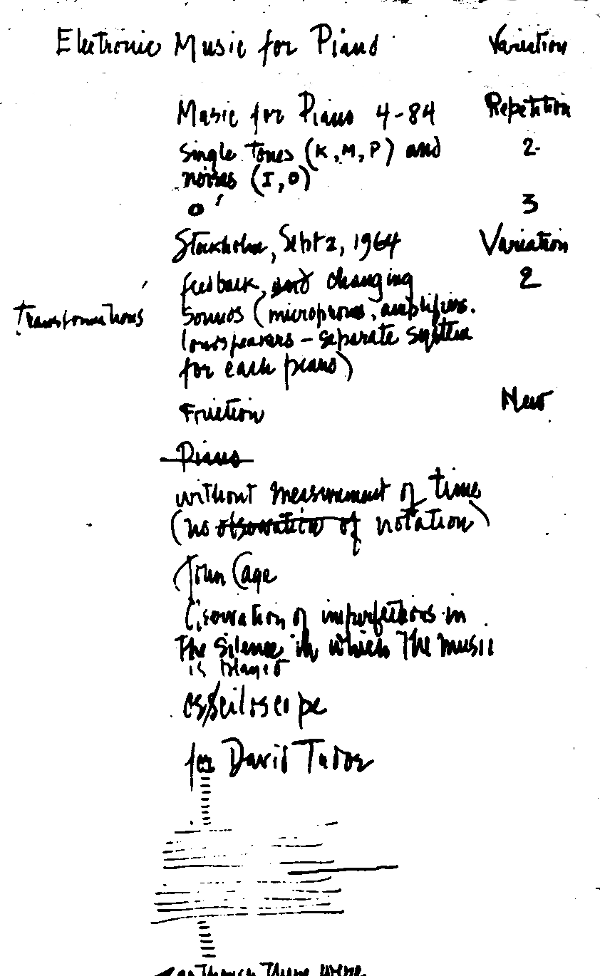

I then happened to look at another Cage piece from the 1960s: Electronic music for piano (1964). It’s a piece I’ve thought about playing for a while now. The score consists of short notes that describe playing Cage’s earlier Music for piano 4-84 with amplification: “feedback, changing sounds (microphones, amplifiers, loudspeakers—separate system for each piano).” Coming off of hearing that story about the amplified toy piano, it was quite clear to me that Electronic music for piano is really just a description of David Tudor’s performance style of that time. Here again, Cage was just wrapping a thin layer of composition around David Tudor’s musical explorations.

And this in turn led me to think about my research on David Tudor’s 1961 realization of Cage’s Variations II. I concluded there that this was a composition more by Tudor than by Cage, that Tudor had bent Cage’s score to his own musical ends:

Given this, it would not be out of the question to call Variations II Tudor’s first composition. The things that define its character are really Tudor’s own compositional choices, his own musical vision. . . . Thus, the motivating force of the realization was Tudor’s conception of his own exploration of a complex amplification system using a piano — looked at from this perspective, it is really David Tudor’s music, not just a realization of Cage’s.

But, given Cage’s story above, couldn’t I really say exactly the same thing about Music for amplified toy pianos? I’m now starting to think that this blurring of the line between John Cage and David Tudor took place over a longer period of time than I previously realized. And by this “blurring of the line”, I don’t refer to Tudor’s creative approaches to performing pieces like Cage’s Solo for piano: there seems to me to be a very real difference. In Solo for piano Tudor took Cage’s indeterminate notations and layered on another system of interpretation to create music. But in Music for amplified piano, Variations II, and Electronic music for piano, he made music and Cage layered on a notation to create a composition. I began to wonder whether some earlier Cage pieces owe more to David Tudor’s creativity (especially as an instrument maker) than I thought.

Reviewing the work list, I discovered that Music for amplified toy pianos was actually the first Cage piece to use contact microphones: was this Cage’s idea or Tudor’s? And what about Cartridge music (also from 1960)? From the correspondence published in Martin Iddon’s new book, it’s clear that the apparatus and probably Tudor’s performing style existed well before the piece was actually composed. Was the performance something that Tudor envisioned first, and then Cage scored afterwards? For all his love of technology, Cage was not a particularly technically adept person. Was Tudor’s growing interest and facility with electronics really the motivating force behind all those technological Cage pieces of the 1960s? What role did he play in the genesis of WBAI (1960), 0′ 00″ (1962), Variations V (1965), Variations VI (1966), and Variations VII (1966)?

David Tudor’s emergence as a composer in his own right is woven in with this series. His first composition, Fluorescent sound, and Cage’s Electronic music for piano were composed at the same festival in Stockholm in 1964. Had Cage written a score to control Tudor’s electronic setup, would we think of this as Cage’s work? By the time of the “9 Evenings” performances in New York in 1966, Tudor and Cage received equal billing: Tudor’s Bandoneon! stood alongside Cage’s Variations VII. By 1968, Cage could write Reunion and acknowledge that the music being gated by his system was composed by David Tudor: they were both composers now.

I think that this line of questioning creates an interesting story line for Cage’s music of the 1960s. That’s always seemed to me like a very fallow period in Cage’s compositional work. He perhaps was working through some mid-life issues in his 50s. Whatever the cause, he wrote far less music during the period, and in general the works are much less substantial. I’ve always thought that they leaned too heavily on others; they aren’t so much compositions as group performances. Perhaps this story of David Tudor fits into this context: Cage was trying to keep up with the younger composer’s musical experiments but not really finding his own voice. Things turn around for Cage with Cheap imitation in 1969. Maybe it was only when Cage was able to drop David Tudor altogether and play the piano for himself that he regained his footing.

Having been a grad student at Wesleyan, which holds Tudor’s archive of original electronic devices, and notations,before the notations were sent off to the Getty Institute, I share your thoughts on Tudor’s

“contributions” and realizations of many of Cage’s pieces. Without David Tudor, Cage would be like the moon without the sun, me thinks, not as bright.