Last year I spent a good deal of time listening to Morton Feldman’s music, trying to get a picture of his entire body of work. I started with the works of the early 1950s and marched forward through the 1960s and 1970s. When I got to 1983, I faced the need to listen to Feldman’s String quartet No. 2, his famous six-hour string quartet, the longest work of a composer who wrote many long works.

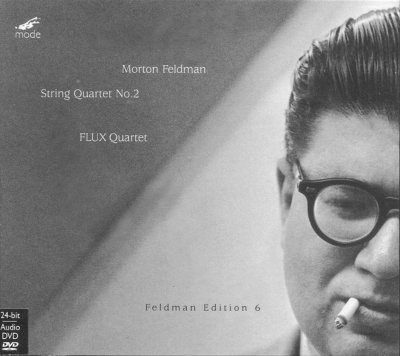

How do you listen to a six-hour string quartet? I decided that the first time through I wanted to hear it in one uninterrupted session. I purchased the DVD version of the Flux Quartet‘s recording so that I could listen to it without having to change CDs. I ripped this so that I could put it on a portable player and not be tied to a single seat while I listened. I chose a Sunday afternoon and kept my schedule clear. I retreated to my office, put on the headphones, and listened from 1:30 to 7:45pm. It was a beautiful experience. I realized that the piece is not just notable for its extreme length: it is a significant work in Feldman’s career. He really discovers a new kind of pacing and imagery in this work that break new ground.

Listening to it was, of course, a marathon. I did not stay in one seat the entire time: I moved around from chair to floor to walking back and forth. My attention waxed and waned, disappeared and reappeared. Like other late Feldman works, this string quartet plays with one’s memory, and over six hours there were plenty of times when I thought I was hearing something I’d heard before, but I wasn’t sure. Not having the score in hand and the not able to go back and re-listen left these questions in my mind: I had to reconcile myself with not knowing exactly what was going on. And finally, after six hours of listening to Feldman’s subtle consciousness, I emerged with my feet a little off the ground.

After this, I took a break in my Feldman survey to do other things; recently I decided to pick it up again. I thought I’d listen to String quartet No. 2 again, just to remind myself of where I was months ago. I decided to listen to it differently this time, though. Writing about his first string quartet, Feldman had compared its longer form to a novel. This inspired me to listen to the piece the way that I would read a novel. I had just finished reading Charles Dickens’s Bleak house, so the tactics for reading a long work of fiction were fresh in my mind.

I listened every morning for periods of 15–30 minutes or more, however much time I had available. It was like reading a chapter or two at a time. I still didn’t have a copy of the score, but I took some notes while listening, in part to record the experience for myself, but also to keep my bearings. I had a friend in high school English class who used to keep an index card in every assigned novel to write down the names of characters so that he could keep them straight. My notes were something like this for the quartet. I was good about listening every day in the beginning, but, like with my reading of Bleak house, I skipped some days as other parts of my life got in the way of my listening time. I had hoped to finish in a couple of weeks, but it wound up taking me the better part of a month to listen to the whole thing.

It was a very different experience from listening straight through, of course. I noticed plenty of similarities to novel-reading. When I was listening daily I was able to keep a sense of continuity in my head, but after a weekend away from it, it seemed more distant when I returned on Monday. I found myself re-listening to a little bit from the day before to remind myself of where I left off, which I often do with novels; on a couple of occasions I flipped back through to recheck something that I thought might be related to what I just heard. I avoided “studying” the piece in any overt way, however. One day I stopped only because I was out of time and needed to get ready for work, but Feldman was going strong and I really could have stayed with it longer. This piece, like a good novel, can be hard to put down.

It was a more concentrated experience than the one-sitting listen. Taken in smaller chunks, my mind stayed fresher, of course, even though my concentration varied from day to day. I found whatever part of the piece I was listening to that morning stayed with me through the day, rolling around in my head, so that I was listening to the piece even when I wasn’t listening to it. By the end, I wrote in my notes that “It’s been a bit of a slog at times, especially towards end. What’s my view of the whole? Do I even have one? If I flipped back through the piece, what would I think?”

And, like reading any great novel or going on any great trip, I find myself promising to do it again, but perhaps in a different way. How else could I go about listening to this piece? I’m already thinking of a few new strategies.

Fascinating comparison, James. I’ve never listened to the Quartet, but the idea of splitting it up like a novel might make it more feasible. (Come to think of it, that’s how I finally listened to “Einstein on the Beach.”)

I love the analogy between experiencing a novel and experiencing the Quartet. I understand what you’re saying about cohesion of thought, listening to the piece straight through. But then again — I never read a novel in a day, even if I have the time. I prefer to carry the book with me (figuratively) for days or weeks on end, making it a part of my life for a span. Makes me feel like I’ve experienced the novel more fully.

It never occurred to me that the same might be true of music. In fact, I’d always assumed music would be the opposite case: better experienced all at once. Now I’ve got an alternative to consider. Thanks.