Recently I’ve had a very engaging e-correspondence with pianist Adam Tendler about Morton Feldman, memory, and memorizing Feldman. Adam and I met at Bard College last year, where I was giving the pre-concert talk for a performance of John Cage’s The ten thousand things in which Adam participated (Adam can be seen in action in the photo above, taken at the rehearsal for that concert). Adam and I have been emailing back and forth about Morton Feldman’s Palais de mari, and it’s been making me want to get back to what I started this blog about five years ago: writing about Feldman’s music.

Adam was the one to bring up Palais de mari:

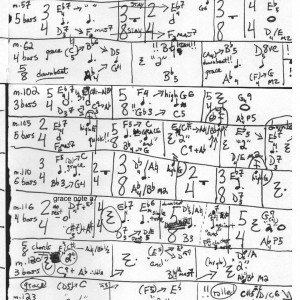

I’ve been thinking of you lately as I attempt to memorize Palais de mari. It’s possibly the most straining musical assignment I’ve ever attempted. I first tried memorizing backwards, which I often do, and realized that my mind was chunking passages and creating little patterns and almost textual clues, so I started writing them down, thinking it would remain (again in reverse order) somewhat straightforward. Obviously it doesn’t (!), and what resulted was several pages of coded maps and hints …

I love maps, and when I was first thinking about Feldman’s late music I thought that drawing different kinds of maps would be a great way to understand them. I’m less certain of that now, but I was eager to see Adam’s memory aid. It occurred to me that examining other people’s ways of remembering Palais de mari would be an interesting way to start building up a picture of the piece.

I told Adam that he was a brave man to try to memorize this music (since in it Feldman was deliberately playing with memory) and asked for more scans of his maps. Adam sent those along and described his work with Palais de mari further. He went into more depth about memorizing this music and why he is doing it:

I finally got through Palais (pretty much) from memory today and yesterday. So now the job will be to keep carving through so that it happens with less and less effort and fatigue, and that the memory goes from one event to the next without too much searching. In my practice, I’ve audibly “shh”d myself when I started thinking too far ahead and began questioning, panicking—”shh”ing myself as if to urge the brain to keep from spazzing out and just trust that when the next thing comes, I’ll know.

I’ve lately approached memory by likening the performance of music (from memory) to how an actor might approach a text-heavy play. The material is indeed all in the mind, and one works to get it there, but it also may have to be triggered into execution. And maybe that’s okay! An actor is triggered by dialogue and action—each event provoking the next. Music seems quite the same. We’re constantly getting feedback that ideally will inform what happens next. With a piece like Palais, or anything long and abstract, I have to trust this process, just as an actor would trust that they do indeed know all their lines, even if it seems impossible to recall or order all at once.

I’ve always thought of Feldman’s late music as having the nature of thought, and this seems to be a reflection of his working methods. In these pieces, we are actually hearing his thought process at work, as I described to Adam:

Yes, not thinking ahead is critical for Feldman, since that’s the way the music was evidently composed. My understanding is that he just started at the beginning and wrote through to the end, with little or no revision. Certainly these late pieces have the quality of thought, the feeling of following his mind forward, changing direction, getting stuck, etc. Passages like that series of dotted quarter chords around measure 110 or so sound to me like erasures: Feldman saying “Nope, this isn’t where it needs to go, let me gather up and start again.” And then his mind becomes collected and concentrated and you get those painfully beautiful expanses.

Or, as I described it later, “Feldman sat down at the piano, and Palais de mari is what happened.” Adam’s way of working interested me because it suggests that the performance of the work itself can also be an expression of the process. Our views were remarkably similar:

It’s funny that you mentioned those measures around 110 in Palais where you hear Feldman sort of focusing and re-focusing, figuring out where to go next… Though relatively early in the piece and relatively early in my own recent round of memorizing, it’s that passage out of the whole piece that feels to me like one of the hardest to remember and get right! Everything else has clicked, more or less, but I still sort of question myself in that one little passage!

Ultimately, working both at the piano and away from it, Adam was able to play Palais de mari from memory. We discussed the difficulty in pinning Feldman’s work down, and he described a fully embodied way of knowing this music that I found striking:

To be guided by ear and inspiration, it seems so audacious . . . . But you’re right, there’s so much to say and yet the music touches us in a way that defies articulation. Also, so much is said for the quiet dynamics and slow tempos, but really people should and could explore how it actually feels to play this music. I’m shocked at how virtuosic this quiet, slow music really feels, and how in a field of such utter concentration, the physical apparatus starts to ask questions back to the ear and rest of the body. This very intense conversation happens between all of the body’s parts, all mediated by this impersonal and unflinching thing of an instrument. The music becomes intensely personal physically, in part maybe because we feel like it should be so easy to execute and of course, like a Schubert texture, one could spend a lifetime trying to get that perfect balance.

As impressive as his accomplishment is, Adam told me that he actually spends very little time actually doing the memorization—maybe ten minutes a day. But he finds that playing from memory is important for his relationship to the audience:

The result I’ve found, though, when I’ve seen performers play without scores (or when people have seen me do the same) is one of increased connection to the music and audience. People trust a performer’s level of commitment, and thus can more easily trust the work. I do think that the commitment itself can become compelling enough for people to surrender to the music itself, and with the removal of the score one does, I think, remove a barrier between the performer and the listener.

I’ve really enjoyed this geeky pianist talk that Adam and I have been having over the past month. And all the while, my copy of Feldman’s Triadic memories was staring at me, daring me to learn it. When I met Aki Takahashi in 2012, I told her that I had learned Palais de mari and For Bunita Marcus. She teased me: “Oh, you’ve started with the easy ones!” Ever since then, I’ve been both tempted and terrified to learn Triadic memories. For a time I just made up my mind that I didn’t need to learn that piece, but recently I have been having second thoughts, and Adam’s email stirred that up further, as I let him know, telling him that perhaps his writing to me out of the blue about Palais de mari was a sign. Adam encouraged me in this (“You should definitely learn Triadic Memories!”). I wrote to Aki to tell her about Adam and casually float the idea of learning Triadic memories, and she was enthusiastic as well. They’ve given me the nerve to start it and to blog about the journey. Stay tuned . . .

Hello James, …and reading your piece has helped me decide to attempt the biographical work again. I’ll be wanting to get in touch with you about these geeky aspects sometime. Meanwhile, I’d best get on with the writing. Best wishes, Julian.

James

Not sure if you read the comments, most of them are years old 🙂

In case you do, I have a great interest in maps, coded or not with this composition.

Would it be possible to get copies of these… from anyone, but the same composition?

What I have in mind is to make into an art (painting and multi-media) and have the music playing when showing these paintings.

Names, dates and where credit to be given for these maps is a must, so I can properly label it within my painting and film that use the same track.

Cheers

Theo