Recently, Douglas Geers and Maja Cerar contacted Frances & me about a paper they were presenting at an electroacoustic music conference. They were researching the history of the Brooklyn College Center for Computer Music (BC-CCM), and they asked us to share our memories of our time there in the 1980s. They provided a survey form for this purpose, but I responded in large part with a version of the following essay.

I never really had any legitimate reason to work at the Brooklyn College Center for Computer Music. I just kept showing up and eventually looked as legitimate as anyone else in computer music at the time.

It started by waiting for Frances. She did have a legitimate reason to be there: she was a graduate student at the college and took the computer music course in 1984. Charles Dodge, one of the leading composers in computer music, was her teacher. The computer in use at that time was a DEC PDP-11. It ran the Unix operating system and the primary synthesis programs the composers used were Barry Vercoe’s Music 11 and, later, Csound. Frances learned how to synthesize sounds from scratch on the computer. As cumbersome as the tools could be at times, they beckoned to her with the promise of sounds that couldn’t be created any other way. They suggested to her, as they had to composers like Dodge and others, limitless possibilities for making music.

But mostly what computer music people did in those days was wait for jobs to finish. The PDP-11 was, by contemporary standards, hardly a computer at all. The main processor of a run-of-the-mill phone today could probably do the work of a hundred PDP-11s in less time. A sound synthesis program that we would expect to run in seconds today would take minutes—possibly many minutes. Frances would program her instrument synthesis instructions, type up the score to tell the computer which notes to create with those instruments, type the Csound command, hit enter, and . . . wait. When the job finally completed, she could hear the results. If it came out the way she intended, great; if not, she’d have to go back and fix whatever it was that wasn’t quite right in the instrument or score, rerun the job, and wait again.

Frances and I met as undergraduate students (on the first day of our freshman year, in fact), and we both came to New York for graduate school. I was in the musicology program at New York University and was living in Manhattan, in the Village. Frances had a place in Brooklyn near the college. Most weekends, I would come out to Brooklyn to stay with her. I was the one who came to Brooklyn in part because she had cats that needed caring for, but frankly, it was also because she was becoming deeply entranced by the possibilities of computer music. She was spending more or her time in the terminal room at the music department, waiting for jobs to run. And so, when I’d come down to Flatbush on a Friday afternoon, I’d go straight to the terminal room and wait, too. The job would finish, she’d listen, and then say “Oh, I see what I did wrong. Let me just run one more job . . . .” And then I’d wait some more. This was my introduction to computer music.

During that waiting time, I started to read Unix manuals. I had recently gotten my own personal computer and was completely obsessed with learning how to program it. I spent hours reading books and working on it, discovering how to make it do what I wanted it to. I knew plenty about my own machine—about Z80 assembly language and the CP/M operating system—but the worlds of Unix and C language programming were new to me. I was curious and easily addicted to anything having to do with computers, so when I came to Brooklyn I read the manuals lying around the terminal room to understand how it all worked. Frances showed me the commands she used doing her work. I became more curious.

Eventually Ken Worthy, the Technical Director and system administrator at BC-CCM at the time, gave me an account on the system so that I could play around with programming. It probably is unthinkable today for someone to just wander in to a university computer center and get set up with an account on the system. But in those days music departments with computer facilities ran their own systems and could administer them however they pleased. And computer music had a culture of encouraging curious people to hang around and see what they could do with the equipment. So now I had something to occupy myself with while waiting for Frances’s “just one more job.”

Frances became more and more serious about creating her music using computers. The possibility of crafting sounds by hand set her imagination on fire and she created Ogni pensiero vola, her first computer music composition. This was the first composition that she felt was authentically her own work in her own voice. Her status changed: she now worked less in the upstairs terminal room and more in the studio itself, where Charles and Ken worked. I hung out there, too, and, in the very communal, collegial environment, got to know everyone: Charles, Ken, Curtis Bahn, Richard Karpen, Janet Murphy, and other composers at BC-CCM.

In the summer of 1986 I finally stopped commuting and moved in with Frances in her apartment on Avenue H in Flatbush. The computer music studio became my place to hang out. Ken left BC-CCM and Curtis took over as the Technical Director. Curtis and I became good friends and I helped him out from time to time at the studio. If he encountered a problem, we’d troubleshoot and work out a solution together—or just commiserate over the fickleness of computers.

I was learning more and more about Unix systems and programming, when I really should have been writing my doctoral dissertation. BC-CCM got one of the first generation of Apple LaserWriter printers, and Curtis let me use it to print my dissertation. I wrote the entire thing in a plain text editor that I built myself for my CP/M computer and formatted it for printing using Unix ptroff. You embedded special codes in the text to indicate the starts of paragraphs, where to use boldface and italics, to embed footnotes, etc. The ptroff software then prepared the print images, which looked just like a phototypeset book. People were used to seeing typescript dissertations, and so my laser printed pages looked amazing. They carried the authority of publication. and I counted on that to score points with my committee.

Engaged in classic doctoral candidate procrastination, I spent much of my time at the studio, programming. Charles, Curtis, and David Arzouman were all writing music using the principles of fractal geometry. It was tedious work to generate these computer scores. My mind was tuned into this kind of systematic, algorithmic method from my work on John Cage’s chance compositions, and I saw that I could create software that would help my composer friends out. I created fromp (for “Fractal Composition”), a language for describing fractal score generators. A composer defined the rules and fromp would then generate the scores following those rules.

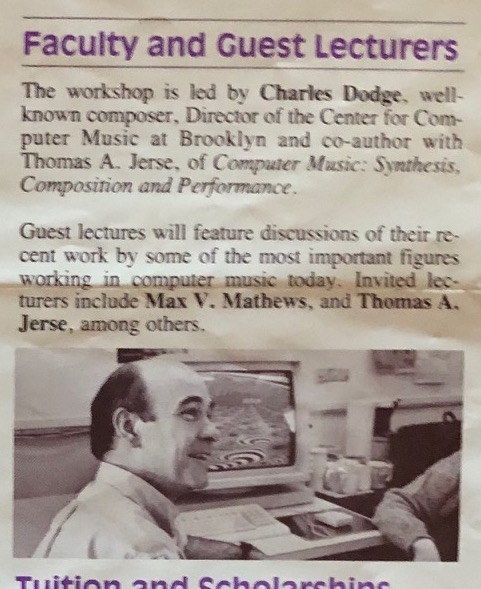

I also had fun with the new Sun 3/160 workstation that the studio purchased at this time. It had the ability to render graphics (the PDP-11, of course, only knew how to talk to dumb ASCII terminals). After reading an article on computer-generated fractal pictures, I followed the recipe and wrote programming to generate pictures to display on the Sun monitor. A photograph of Charles sitting in front of one of these was used in the advertising for the BC-CCM summer computer course. The studio got a digital signal processor board that I tried (and failed) to get to do something useful. Brad Garton of Columbia University was working on the Unix driver for a sound card for the Sun. He dropped by the Flatbush studio occasionally, and I helped him as much as I could.

Throughout this period, I continued to spend time waiting for Frances to run “just one more job.” I waited for her to run the endless jobs needed to create John Cage’s Essay, a monumental work of computer speech synthesis (and which today could probably be created in real time). I also waited for Curtis’ jobs to finish, for David Arzouman’s jobs to finish, for Judy Klein’s jobs to finish. Because there was only one digital-to-analog converter for the entire studio, only one composer could play sound at a time. And so I heard all these composers’ music—as well as Charles Dodge’s music and Larry Austin’s (when he was a visiting composer). I listened to their work in progress, their failures and mistakes and discoveries. While we waited, we played “snake” on our terminals. At times I did my waiting for Frances from the comfort of my desk in the Avenue H apartment, talking with her via a terminal session connected over a 1200 baud modem—the very slow and cumbersome ancestor of texting today. Composers working on computer music were an integral part of my life. The computer music studio was as much a social entity as an academic or musical one. For the composers working in computer music at Brooklyn, it was like a geeky version of the Cedar Tavern. It was our home away from home.

I finished writing my dissertation in the spring of 1988 and it looked beautiful in the laser-printed copy I submitted: unassailable by any committee. Frances finished her master’s degree at Brooklyn College. We both planned to move out of Brooklyn that summer: she was going to Princeton to start the doctoral program and I was going to Wisconsin for a one-year visiting professor job. We decided to get married a week or so before we left. The ceremony was at the Brooklyn Marriage Bureau near Borough Hall on August 3rd. Afterwards we had lunch with Frances’s dad and sister, then took the #2 subway back to Flatbush. Without even thinking about it, we went straight from the station to the BC-CCM studio to tell everyone the good news. Then we left the studio and went to our other home on Avenue H.