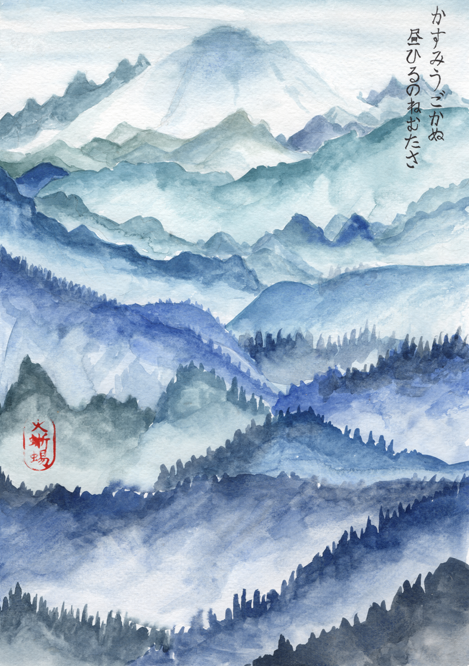

Before studying Zen, men are men and mountains are mountains. While studying Zen, things become confused. After studying Zen, men are men and mountains are mountains. After telling this, Dr. Suzuki was asked, “What is the difference between before and after?” He said, “No difference, only the feet are a little bit off the ground.”

This story is from Cage’s famed lecture “Indeterminacy: New Aspect of Form in Instrumental and Electronic Music” (1958). It has an interesting history that reveals much about Cage’s relationship to Zen Buddhism. What he presented as a classic Zen saying was actually his own unique variant, one that took it away from its Zen roots.

The story has earlier appearances in Cage’s writings. He told it in “Lecture on Something” (1951); this was in fact the first mention of Zen in any of his writings. Here, however, the part about Dr. Suzuki and the feet being off the ground did not appear. Cage added this when he told the story the following year at the very opening of his “Juilliard Lecture” (1952).

When I researched the origin of this saying, I couldn’t find any other sources—at least not in the form that Cage told it. The only citations of the “men and mountains” saying other than Cage’s are by people who got it from Cage. What I did find were multiple references to the same three-part statement (before, during, and after studying Zen), but applied to “mountains and waters” (occasionally translated as “mountains and rivers”). Suzuki himself told it this way in the introduction to his first set of Essays on Zen Buddhism (1927):

Before a man studies Zen, to him mountains are mountains and waters are waters; after he gets an insight into the truth of Zen through the instruction of a good master, mountains to him are not mountains and waters are not waters; but after this when he really attains to the abode of rest, mountains are once more mountains and waters are waters.

Suzuki attributed this saying to the Chinese master Qingyuan Weixin (Japanese: Seigen Ishin). Alan Watts told the same story in his The Way of Zen (1951), this time telling it from the master’s point of view:

Before I had studied Zen for thirty years, I saw mountains as mountains, and waters as waters. When I arrived at a more intimate knowledge, I came to the point where I saw that mountains are not mountains, and waters are not waters. But now that I have got its very substance I am at rest. For it’s just that I see mountains once again as mountains, and waters once again as waters.

Other authors reference this story, almost always couching it in the same way that Watts does: Qingyuan Weixin explaining his own personal experience.

The “mountains and waters” saying of Qingyuan Weixin is surely the ultimate source of Cage’s “men and mountains” story. But why did Cage tell the story in the garbled form of “men are men and mountains are mountains?” The answer has to do with the actual meaning of the saying and Cage’s garbled version of that meaning. Cage understood this story to be about something quite different from what Qingyuan Weixin, Suzuki, and Watts meant, and the “men and mountains” formulation highlights Cage’s own distinctive take on the story.

“Mountains and waters” and Zen

In the context of Zen Buddhism, the “mountains and waters” saying is about the change in perspective during a lifetime of practice: the three phases of before, during, and after studying Zen. In the introduction to his translation of the The Zen teaching of Huang Po on the transmission of Universal Mind (1958), John Blofeld explains these stages using the moon and trees instead of mountains and waters:

To the great majority of people, the moon is the moon and the trees are trees. The next stage (not really higher than the first) is to perceive that the moon and trees are not at all what they seem to be, since “all is the One Mind.” When this stage is achieved, we have the concept of a vast uniformity in which all distinctions are void; and, to some adepts, this concept may come as an actual perception, as “real” to them as were the moon and the trees before. It is said that, when Enlightenment really comes, the moon is again very much the moon and the trees exactly trees; but with a difference, for the Enlightened man is capable of perceiving both unity and multiplicity without the least contradiction between them!

The three phases thus represent the ordinary understanding of things before investigating further; the initial understanding arising from Zen study; and then the ultimate, deepest understanding that arises after a lifetime of practice.

“Men and mountains” to “Men and sounds”

Cage, however, read the story quite differently. When he told it in his “Juilliard Lecture” he followed it with a restatement in terms of his own view of music and sound:

Now, before studying music, men are men and sounds are sounds. While studying music things aren’t clear. After studying music men are men and sounds are sounds.

In Cage’s view, the study of music makes sounds part of “an abstract process … called composition.” The linchpin of this whole fabrication is the composer’s ego. Sounds are made subservient to the ideas or feelings they supposedly express, and the ideas or feelings serve “to show how intelligent [or emotional] the composer was who had [them].” For this abstract projection of ego to work, one must “imagine that sounds are not sounds at all but are Beethoven and that men are not men but are sounds.” Cage’s answer to this delusion is to just stop studying music, “to stop all the thinking that separates music from living.” Then, once again, “sounds are sounds and men are men, but now our feet are a little off the ground.”

What Cage presented in 1952 as a parallel to Qingyuan Weixin’s Zen saying was a continuation of the underlying theme of his musical thinking of the late 1940s and early 1950s. For Cage the problem of musical composition was to disengage it from the strivings of ego that were encouraged by modern Western musical practice. Sounds are expressive in themselves, and the composer should remain silent—say nothing—so that this natural expressivity can emerge.

The shift from “mountains and waters” to “men and mountains” thus made Qingyuan Weixin’s saying align with Cage’s own concerns about music with regard to the opposition of ego (“men”) and nature (“mountains”). Telling the story of the effect of studying Zen using “men and mountains” allowed this connection to “men and sounds” and ultimately to Cage’s central point that “sounds are not Beethoven.”

But the change wasn’t just a change in imagery; it was a change in the fundamental point of the saying. In the Zen saying, the distinction between mountains and waters is blurred while studying Zen because they both are encompassed by “the One Mind” (as Blofeld put it). In Cage’s version, he wanted to make it clear that men and sounds/mountains are completely different things. With the opposition inherent in this view, Cage’s presentation of this saying strayed far from its Zen origins. He inverted a story about the cultivation of a nondual view of the universe into a story about the opposition of men and sounds.

In Cage’s musical version of the saying (“men and sounds”), the middle state of confusion is not associated with a partially-understood truth reached through disciplined practice and inquiry (as it is in the original Zen saying). Instead, the confusion of men and sounds is a state of delusion about reality that is reinforced through the pursuit of a false path: studying music. In Cage’s view, there are only sounds, and the ideas of music are defilements that obscure our clear comprehension of sounds, unadorned and expressive in themselves. In Cage’s retelling, then, Qingyuan Weixin’s “mountains and waters” becomes a story about the recovery of a lost innocence. Rather than describing the progressive stages of practice, it tells the story of seeing life clearly again by erasing the conceptual overlay of false views.

To be sure, this story line of innocence lost and regained is latent in the Zen saying; Suzuki himself suggested it. In the paragraph before he cited Qinyuan Weixin, he wrote:

Zen maintains . . . that all the fetters and manacles we seem to be carrying about ourselves are put on later through ignorance of the true condition of existence. All the treatments, sometimes literary and sometimes physical, which are most liberally and kindheartedly given by the masters to inquiring souls, are intended to get them back to the original state of freedom.

But Cage’s vision of this process elides the extended hard work—the “treatments given by the masters”—that is essential to Zen. For Cage, the ultimate enlightened state of simply hearing the nature of sounds came from just stopping musical thinking. Unlike Qinyuan Weixin’s Zen, Cage did not present this state as being the most refined state of a lifelong practice. Cage gave no sense of a path that leads one to “stop all the thinking that separates music from living.”

So, when we investigate this particular example of Cage citing a Zen story to explain his own musical work, we find very little Zen in it. Cage misstated the actual saying of Qinyuan Weixin, and then he presented a personal interpretation of its meaning that had little to do with its Zen origins. Indeed, it could be seen as antithetical to Zen in some regards. Carolyn Brown’s description of Cage’s use (and misuse) of others’ ideas applies here: “in his own unique and perhaps intellectually outrageous fashion, he made their ideas his own, now blunderingly, now brilliantly synthesizing.”

The bothersome question is: what did it mean for Cage to attribute this saying to Zen, to Suzuki? In both “Lecture on Something” and “Indeterminacy” he presented the saying (in his altered version) with no further explanation at all. This followed the example of Suzuki himself; he was fond of letting cryptic Zen sayings stand on their own. When he encountered the “mountains are mountains and waters are waters” saying, I’m sure Cage heard the resonance with his own dictum of “sounds are just sounds.” By presenting this story in a way that suggested a distinction between men and sounds, Cage harnessed the spiritual authority of Zen and Suzuki to his musical work of letting sounds be themselves. The “intellectually outrageous” aspect of this was that his presentation had so very little to do with letting Zen be itself.

Sources & asides

Here are the sources of Cage’s telling of the “men and mountains” story: “Indeterminacy”, Silence (1961), p. 88; “Lecture on Something”, Silence, p. 143; “Juilliard Lecture”, A year from Monday (1967), pp. 95–96.

Suzuki tells the “mountains and waters” story in his Essays on Zen Buddhism, first series (1927), p. 12. Alan Watts tells it in The way of Zen (1951), p. 126. The explanation of the saying (using the moon and trees) by John Blofeld appears in his “Translator’s Introduction” to The Zen teaching of Huang Po on the transmission of Universal Mind (1958), pp. 20–21. All of these are books that Cage would have been familiar with in the 1950s. A handy compilation of references to Qingyuan Weixin’s saying appears online at the ZENline by Terebress site.

Cage’s interpretation of the “men and mountains” story appears in “Juilliard Lecture,” A year from Monday, pp. 96–98. The statement from Suzuki about returning to the original state of freedom appears on p. 11 of his Essays on Zen Buddhism, first series.

Carolyn Brown’s description of Cage’s intellectual borrowings is from her memoir Chance and circumstance (2007), p. 38.

The chronology of this story and what it says about Cage’s attendance at Suzuki’s classes is a bit of a puzzle. When Cage first told it in early 1951 in “Lecture on Something,” he didn’t mention Suzuki at all. In the “Juilliard Lecture” of 1952, he identified the saying as being told by Suzuki “in the course of a lecture last winter on Zen Buddhism.” This could mean the winter of 1950–51 or 1951–52, depending on the exact date of the “Juilliard Lecture.” As I’ve pointed out above, there are sources for the saying that Cage would have had access to prior to his 1951 “Lecture on Something.” If he didn’t hear it from Suzuki until the winter of 1951–52, he could have read it in Suzuki’s Essays or heard it from Watts directly before telling his variant version in “Lecture on Something,” thus explaining why this version doesn’t mention Suzuki’s lecture as a source. Alternatively (or maybe in addition), he heard this in a lecture by Suzuki that winter of 1950–51 and just failed to mention this in “Lecture on Something.”