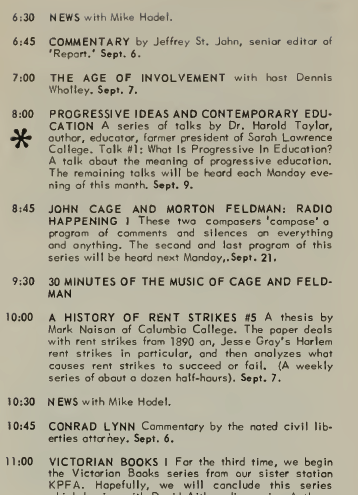

The image above is from the September 1966 issue of Folio, the program guide for radio station WBAI in New York City. The listing is for the evening of Monday, September 5th and is a representative sample of the wide-ranging, educated, left-leaning conversations that were taking place on the air at that time (“Progressive ideas and contemporary education”, “A history of rent strikes #5”, “Victorian books”). The prime-time 8:45 PM slot is occupied by the first broadcast of the John Cage/Morton Feldman Radio happenings:

These two composers ‘compose’ a program of comments and silences on everything and anything. The second and last program of this series will be heard next Monday, Sept. 21.

Despite the listing’s promise that there would only be two of these, there ultimately were five Happenings broadcast at WBAI between September 1966 and April 1967.

The use of the term “happening” suggests something free, wild, spacey: it is a term very much of the period. In the context of art history, it is a term we associate with John Cage. The artist Allan Kaprow coined the term in the late 1950s for his works, works we would label today as “performance art”. But all the art history texts will point to the event that Cage staged at Black Mountain College in 1952 as the original “happening”. It later took on a meaning in the wider culture, where any staged event could be referred to as a “happening”, such as the “peace happenings” of 1967, the “Summer of love”.

The title of the Cage/Feldman show is an early example of this broader usage of “happening”. As far as I can tell, this is the first use of the term at WBAI outside of the discussion of Kaprow’s work. It will appear more frequently after this: a show with Andy Warhol in 1967 was billed as “a hemi-demi-semi happening”, for example. The listing for the Cage/Feldman show clearly suggests that something similarly “far out” was happening with Cage and Feldman. The implication is that this will be one of those crazy composed talks that Cage was notorious for, that he and Feldman were going to take over forty-five minutes of airtime to scatter random words out into silent spaces. The reality was much different.

Unstructured conversations between John Cage and Morton Feldman: that is really all that the Radio happenings were. There was nothing “composed” about it, nothing “musical” about it. They did not appear to have any predetermined agenda or subjects for their conversation. The results are quite straightforward and seem even conservative, given the title. They probably both wore jackets and ties (although we have no photographic evidence for this).

And yet there is something special about these broadcasts that at first may elude us. The premise was quite simple: put these two composers in a room with a microphone and let them talk for an hour. If there is anything unusual about the programs, it is this lack of any third party. There is no moderator and nobody, seen or unseen, putting questions to them. Their manner of speaking gives the impression that they felt unselfconscious, unobserved even by an engineer. It is very much as if they were sitting in someone’s living room, alone, catching up with each other about their lives and work. Feldman opens the third Happening by saying “John, it’s marvelous seeing you again … It seems as if the only time we get a chance to talk with each other is on the radio.”

Whose idea was it to do these programs in this manner? Their specific history is unknown, the principals all deceased, so we can only speculate. The shows were produced by Ann McMillan, who was the music director at WBAI at that time. McMillan was a composer of electronic music who was interested in the use of recorded natural sounds, and especially animal voices, as a basis for compositions. She worked with Edgard Varèse and felt deeply influenced by his work. It seems likely that her connection to Cage and Feldman came through her work with Varèse and her connections in the New York new music scene in general.

There are reasons to believe that McMillan’s primary connection was with Feldman. She interviewed Feldman for WBAI for a broadcast on May 13, 1963, well before she became music director there. It appears that Feldman was the point of contact to schedule the sessions with Cage. At the end of the fifth Happening, Cage tells Feldman to “let me know when they need some more and we’ll make them up.” Cage was no longer living in the city at this time (he moved to Stony Point in the late 1950s), so it makes sense that Feldman, still based in New York City, would be the one to work more closely with McMillan and the radio station.

But who came up with the format for the shows? McMillan was a sensitive and creative producer and could very well have seen the potential in leaving these two strong musical personalities and conversationalists alone and letting the shows emerge on their own. Or she may have approached Feldman about doing another show and Feldman suggested bringing Cage on board. Or he could have approached Cage on McMillan’s behalf about doing something, and the idea of simple conversation was Cage’s idea. Or, perhaps the most likely story, McMillan lined up Cage & Feldman to fill an hour’s broadcast time, they showed up with nothing specific prepared, and just winged it.

However it happened, in deciding to just sit down and talk they were drawing upon a shared history of conversation. Feldman often recalled with great fondness and nostalgia the period immediately after he and Cage met in the early 1950s. These were the halcyon years for new music and art in Feldman’s view: “What was great about the fifties is that for one brief moment—maybe, say, six weeks—nobody understood art. That’s why it all happened.” And a prominent, even central part of this experience were the long conversations that Cage and Feldman had.

There was very little talk about music with John. Things were moving too fast to even talk about it. But there was an incredible amount of talk about painting. John and I would drop in at the Cedar Bar at six in the afternoon and talk with artist friends until three in the morning, when it closed. I can say without exaggeration that we did this every day for five years of our lives.

One could rightly say that those conversations in the early 1950s, unheard by anyone but Cage, Feldman, and perhaps a few others, made history. The Radio happenings, fifteen years later, are an echo of those talks, not a recreation of their content, but a bringing together of some of the conditions in which they occurred: the two principals, the privacy, the expanse of time. In the next installment of this series, I’ll look at the content of these public-yet-private conversations.

Next in this series: What happened at the Happenings