For Bunita Marcus opens with a clear call to our attention. With these first six notes, we step over the threshold and into the journey of the piece. We know that we are in this for the long haul: Morton Feldman’s late works are notorious for being marathons. He composed For Bunita Marcus in 1985, immediately after his four-hour For Philip Guston, and two years after his six-hour String Quartet (II). These earlier works make an hour-long solo piano piece seem short. Still, it is a long time to sustain a single movement, a single journey, and we inevitably have this in mind as we take the first step: so this is how it starts.

For Bunita Marcus, like all the late Feldman works, is an adventure that takes a relatively long time to play out, but which is remarkably lacking in heaviness. We may expect an epic, but we get something much subtler. Indeed, what we get is the present moment, in all its beauty, over and over again. If we surrender to the musical image that is right in front of us, a piece like For Bunita Marcus is an easy world to enter into and to explore with Feldman. We step into the silence after that first six-note motto, and we wonder: What comes next? The next hour and a quarter is spent doing nothing more than discovering what comes next—and the next thing after that, and the next after that.

The world we have entered is, as with all of Feldman’s music, one that is low-definition. Alex Ross has written that listening to Feldman’s music “is like being in a room with the curtains drawn.” The sonic surface of his music has a minimum of contrast, flat but rich with shadows, making it difficult at times to pin down what it is you are hearing. In the case of For Bunita Marcus, these shadows come in part from the reverberations of the piano, whose pedal is mostly held down throughout. There are no noticeable changes in tempo, no strong rhythmic distinctions. The score is devoid of phrasing or articulation markings. Most of the music is in the middle register of the piano. Texturally, it is mostly just single notes in various patterns.

It sounds like a bore, but instead it commands our attention right at the start. The predominant image is of a single sustained, wavering line. It moves with an irregular rhythm up and down chromatically, so that the weight and location of the line is blurred. This line refracts through higher and lower registers in the piano, and this movement up and down will inspire new musical images throughout the course of the piece. In the beginning, though, it is the horizontal line that fully occupies our attention, pulling us forward like a process unfolding. The curtains in Feldman’s room may be drawn and the music may be in the shadows, but it has a restless energy that keeps us alert to where we are going right now.

The line moves through time, and then breaks off, leaving us listening to the reverberations as they die away. Then it picks up again, changing direction, angling up or down, and then stops again, dying away. Feldman’s very late pieces move in this kind of rhythm, alternating sonic images and silences. At the outset of For Bunita Marcus, the line is more continuous and sound predominates over silence. Later in the piece, after the line has unfolded itself into more open patterns, the rhythm of sound and silence becomes more even, more like breathing. The silences keep bringing our awareness back. They sharpen our anticipation of the next point of contact with Feldman’s musical world. We make that contact and then sustain attention, taking in the next arising image until it, too passes away into the silence.

The arising of the image, the expression of the image, the passing away of the image: this process happens over and over in For Bunita Marcus, giving the music the character of thought, or of consciousness itself. Feldman often disparaged the supremacy of “ideas” in music, and he is often portrayed as a composer whose music is purely sonic, purely sensual. But there is perhaps no other music I know of that is as finely attuned as Feldman’s to the nature of the mind, of consciousness, of mental processes.

What do we call these things that appear in the consciousness of For Bunita Marcus, arising out of the silences? I have used the word “images” to describe them; Feldman tended to call them “patterns”. They are generally short, identifiable musical events with a particular profile of pitches and rhythms. Feldman explains: “For me patterns are really self-contained sound-groupings that enable me to break off without preparation into something else.” They have particular colors, moods, and weights. If we want to think of Feldman as being like a painter, patterns are the medium with which he paints his music.

“Patterns are ‘complete’ in themselves, and in no need of development,” Feldman wrote, “only of extension. My concern is: what is its scale when prolonged, and what is the best method to arrive at it?” How does Feldman extend his patterns? Repetition, of course, but while there are plenty of strict repetitions of patterns in For Bunita Marcus, it would be oversimplifying to say that Feldman achieves scale simply through repetition. As often as not, the thing marked to be repeated is a sequence of slightly different iterations of the same pattern, surrounded by silences of different lengths. This breaks up the simple repetition and creates a different feeling: a sense of mental reflection on the musical image. It is brought to mind, and after a pause it is brought to mind again with a slightly different focus, and again after that, this time as it was in the beginning, and then once again.

Besides framing repeated patterns in silence, Feldman keeps the patterns constantly changing, but in ways that do not necessarily move in any particular direction. The rhythms of the pattern are constantly shifting, a sixteenth-note change here, an eighth-note change there. The pitches may move to a higher or lower register, or be inflected up or down a semitone or two. These slight irregularities give the images a floating quality: not “development” in the usual sense, because we are not going anywhere. The images are just subtly shimmering in our hearing. Sometimes the changes do have a feeling of exploration, of Feldman trying things out (“what would it be like to move that pitch up a step?” “How about if I add a grace note?”). There is a rapt attention that develops here.

At times, a particular sonority so fills the attention of the work that the patterns are purely rhythmic articulations of the one sound. Patterning here is a way for the piano to extend a single chord for minutes at a time, enlivened by the changing inner rhythmic articulations. The musical world has come down to a single point, often one of great beauty. These are times of deep concentration, a complete saturation in the musical image. Then again, there are moments when this concentration dissipates, when the path of the piece appears uncertain, tentative. Here the energy scatters and the images flicker, passing away just as they arrive, leaving us wondering where we are going next.

It becomes difficult at times to tell whether these are mental states that are being portrayed by the music, or whether they are Feldman’s mental states while composing it, or whether they are occurring in our own minds as we listen. Perhaps it is all three happening at once. Listening to late Feldman is as much about the stream of our own experience of the piece as it is about the continuity of the piece itself. There are times when we as listeners are deeply attentive to these reflections on musical images, these small changes, these explorations, these extensions that saturate us into the thought. And there are also times when we are distracted, and when we suddenly re-arrive in the moment. Patterns develop from other patterns without our noticing. They stabilize for a time, and in a moment we suddenly awaken to them. We have the impression that this is something that has been going on all along, like our breathing, something that we are just now noticing for the first time.

In For Bunita Marcus, memory is something that Feldman explicitly manipulates in us as listeners. Besides the moment-to-moment reiteration of patterns, there are larger-scale, longer-term repetitions. Looking at the score, we can see that there are particular tactics that Feldman employs to keep these repetitions from becoming architectural (as in a traditional A-B-A form). There is one place in the piece where an entire page of earlier music is repeated, only with the five lines of music on the page in a different sequence. In another spot the page ten pages back is cut up and rearranged. These kinds of memory games produce a state in us of simultaneous recognition and uncertainty: we know that we’ve heard this before, but can’t quite bring it up clearly in memory. This is where the size of the work begins to have an effect, too. It’s just too long to keep it all in memory, too long to compare the parts to each other, too long to keep track of the turns we’ve taken to get to where we are now. We have no choice but to just be in it, following one thing after the other.

Not that there isn’t a trajectory to the piece. Discussions of pieces like For Bunita Marcus often fall into a rhythm of “this happens and then this happens and then this other thing happens.” To be sure, this is often the felt sense of a Feldman piece, early or late. But here in For Bunita Marcus, there are times where there is a perceptible progression. We feel that we are going deeper into the imagery of this musical world. There are points at which we can feel a deeper concentration arising. It is also immediately apparent to us when this concentration falls apart and we move on, but these resting places become deeper as we continue on the path of the work.

And where does it wind up? There are the places of deep stillness that emerge, especially late into the piece, as if made possible by the journey we’ve taken so far. The mood of the piece changes. The edginess and subtly nervous energy of the opening gives way to a more expansive sweetness and beauty in the latter part of the piece. There are passages of grandeur, with chords dominating for the first time, alternating with a pattern of tender beauty that Feldman keeps coming back to, abiding there almost to the ending. Then the whole energy of the piece is disrupted and quickly burns out, floating off into silence.

§ § §

Listening to For Bunita Marcus is a 75-minute journey through different mental and musical states, requiring a particular kind of attentiveness. Maintaining this awareness over such a long, sustained period is a challenge. Performing For Bunita Marcus is a similar challenge, but requires a different kind of attentiveness—and physical stamina on top of that. Just as Feldman is keenly aware of the psychology of listening, he is also in command of the psychology of performing. He guides the mental state of the performer just as surely as he does that of the listener.

The primary mechanism by which this is done is the notation of the music, particularly the notation of rhythm. When he began writing music using repeating patterns, Feldman recognized that getting the right notation for these would be critical. In 1981 he wrote of patterns: “If notated exactly, they are too stiff; if given the slightest notational leeway, they are too loose.” In a score like For Bunita Marcus, rhythmic details given in the notation may not be apparent to the ear at all, but nevertheless have an impact on the performer’s concentration and hence on the music as played. Feldman came to see patterns as “notational images”: “A tumbling of sorts happens in midair between their translation from the page and their execution.” In For Bunita Marcus, the score is more than just a blueprint for executing the sonic patterns—it is a platform for engagement with the performer, engagement which contributes to the organic vitality of the music as it is heard and felt.

Performers approaching this music may thus be a bit intimidated by the challenges of Feldman’s rhythms and the level of concentration that they require. Much of the piece is notated as alternating measures of very slightly different lengths: three eighth notes versus five sixteenth notes. This keeps the pianist alert and actively aware of the changing meter and rhythms. But the details here can be deceptive. While Feldman may have notated a subdivision of five sixteenth notes into six equal parts, for example, he was, according to Aki Takahashi, “not scientific about rhythms.” Notations like this are as much psychological as musical. Indeed, Feldman loved rubato and called for it often in Takahashi’s playing when she was preparing the early performances of pieces like Triadic memories and For Bunita Marcus.

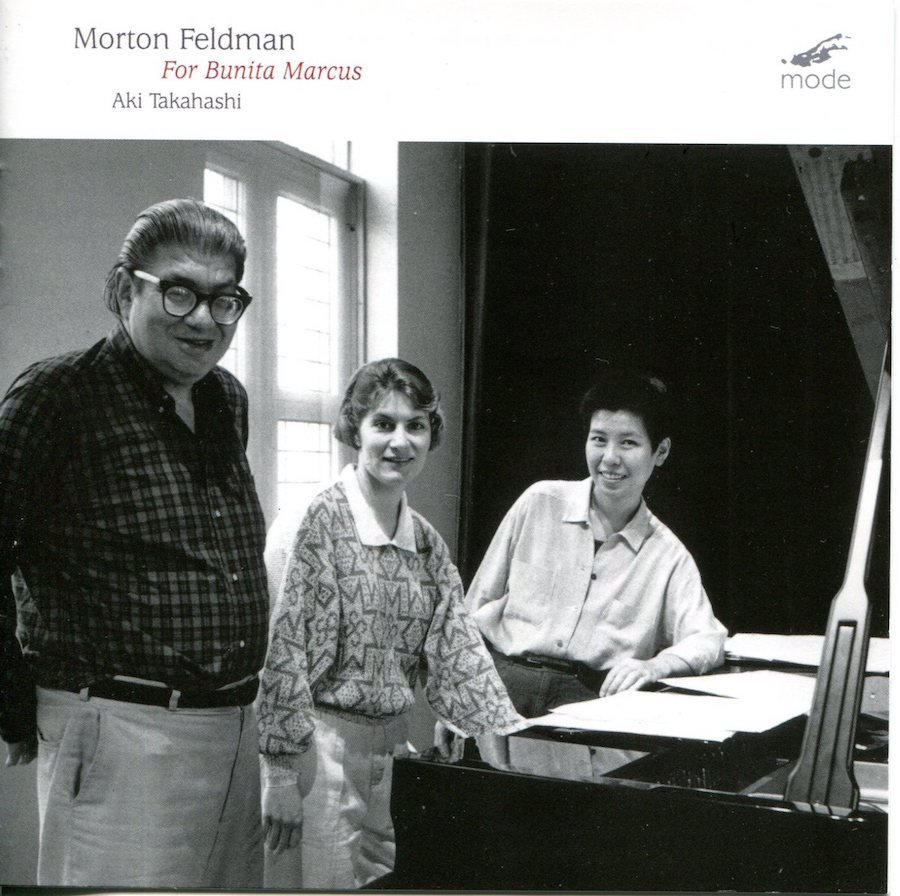

Aki Takahashi had a long and close working relationship with Morton Feldman. They met in 1979 in Japan, but Feldman had heard of her playing from friends in Europe. He invited her to Buffalo to join Creative Associates at the Performing Arts Center there. Not long after her arrival she attended a performance of Feldman’s first string quartet in New York City. She was overwhelmed by the hour-plus-long quartet, generally considered the piece that begins Feldman’s late period. She immediately asked Feldman to compose a piece for her of the same duration. His response was Triadic memories, jointly dedicated to Takahashi and Roger Woodward.

By the time he was in his sixties, Feldman noticed a change in his composing practice: he was no longer just writing pieces, he was writing pieces for particular performers. He called them “casted pieces” and recognized this as an important change to his way of thinking about performers: “They’re not just playing notes, it’s this person playing.” After Triadic memories, Feldman composed all his piano music for Aki Takahashi. In remarks made before the US premiere of Triadic memories, he described Takahashi as “absolutely still”, “undisturbed, unperturbed, as if in a concentrated prayer.” He found that her concentration was transmitted to the audience; a performance by her was “like a séance.”

There is no doubt, then, that Aki Takahashi’s artistry was one of the sources for the deep concentration and spacious beauty that unfolds in For Bunita Marcus. We are fortunate to have this recording, made in 2007 but only now being released. She premiered the work in 1985 in Middelburg. For Bunita Marcus was the second half of the concert. As the sun set, the stage got dimmer and dimmer. Due to a lighting mistake, Takahashi’s score fell further and further into the shadows. But she continued on and finished the piece without a fault. As she says about the very long late works, “once it’s started, I’m afraid to stop.”Feldman was deeply moved by Aki Takahashi’s performance. A year after For Bunita Marcus, he wrote another piece for her: Piano and String Quartet. He called it “Aki’s quintet,” and said “I couldn’t have written it without her.” He further called it “my favorite piece in my whole life. I could die very happily, now that I wrote the Piano and String Quartet. It has everything I ever wanted.” Listening to this recording of For Bunita Marcus, we, too, can be pulled into Aki Takahashi’s séance, into the hushed pianistic world of Morton Feldman, and feel a similar sense of gratitude for her concentrated artistry.