As all critics have noted (including myself), Cheap imitation represents a stylistic discontinuity for Cage: it is wholly unlike the works that made him famous in the 1950s and 1960s. In this sense it is an exceptional work and begs the question of why it is the way it is. The immediate and obvious answer is that Cage needed to make a copyright-free version of Erik Satie’s Socrate to accompany Merce Cunningham’s dance Second hand. But I haven’t read any analysis that looks closely at either Satie’s “symphonic drama” or Cunningham’s dance to see how they relate to the compositional decisions that Cage made in Cheap imitation.

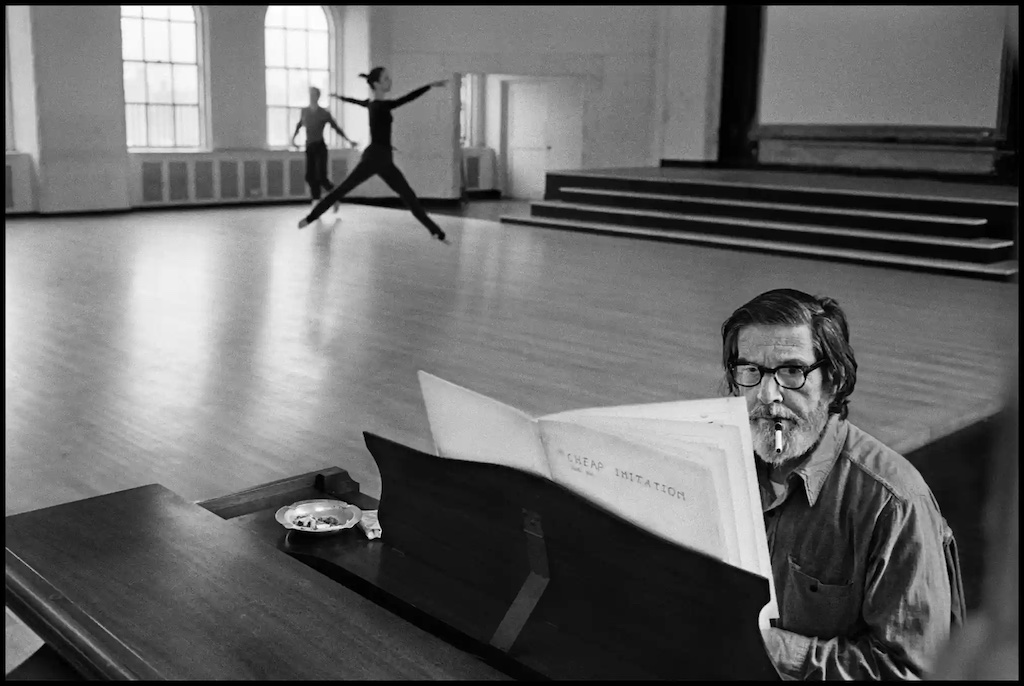

Let me recap the origin story of the dance and the music. In 1944, Cunningham made a solo dance to the first movement of Socrate. For this dance, titled Idyllic song, Cage played a piano reduction of the Satie. Cage always wanted Cunningham to choreograph the other two movements of Socrate, but this went nowhere. In 1968 or 1969, Cage picked up this project again and made a two-piano transcription of Socrate. Cunningham started to think about it, listening to a recording of Socrate to immerse himself in the music. He preserved the original 1944 solo and created new dances for the other two movements. A month before the scheduled premiere, Cage informed Cunningham that he was unable to get permission from Satie’s publisher to use his transcription. Cheap imitation was the solution to this problem. Cunningham was concerned that they wouldn’t have time to rehearse with the new music, but Cage reassured him that it would be. It was, but it was close: the date on the score is 14 December 1969, and the dance premiere was on 8 January 1970.

Cheap imitation was a departure for Cage, and Second hand was also a stylistic anomaly for Cunningham. It was meant to be an extension of his 1944 work (the first movement solo was used unaltered) and so stands apart from where his choreography was going in 1969. By then, he famously made his choreography completely independent of any music. But Second hand is danced to the music, which is why Cage had to make a phrase-for-phrase duplicate of Socrate.

But it’s not just the phrase structure of Satie’s music that was important to Cunningham. In creating the new parts of the dance, he immersed himself in the music of Socrate, which was a piece he loved (he described it as “an extraordinary piece of music”). I would go further and say that the content of the texts of Socrate were significant as well. The three movements are based on excerpts from three different dialogues of Plato. Each movement captures Socrates in a different context:

- “Portrait of Socrates” (from Symposium). Alcibiades, an Athenian statesman, praises Socrates and the beauty and power of his words. He compares Socrates to a statue of the satyr Silenus. Where the satyrs charmed men with the melodies of their flutes, Socrates does so with his words, words that bring Alcibiades to tears. After Alcibiades’ speech, Socrates acknowledges his praise.

- “On the banks of the Ilissus” (from Phaedrus). Socrates and Phaedrus go for a walk along the banks of the Ilissus river on a summer day. They are looking for a comfortable spot where Phaedrus can read to Socrates a recent speech on love by the orator Lysias. As they walk barefoot along the stream, they describe the lovely weather and surroundings and comment on the history of the place. They find a shady, grassy spot that delights Socrates.

- “The death of Socrates” (from Phaedo). Phaedo recounts the last moments of Socrates’ life. It is a touching description of the equanimity of Socrates towards his fate, the sadness of his disciples, and the distress of the jailer who must give Socrates the poison. Socrates drinks the poison and dies. “Such was the end . . . of our friend,” Phaedo concludes, “concerning whom I may truly say, that of all the men of his time whom I have known, he was the wisest and most just and best.”

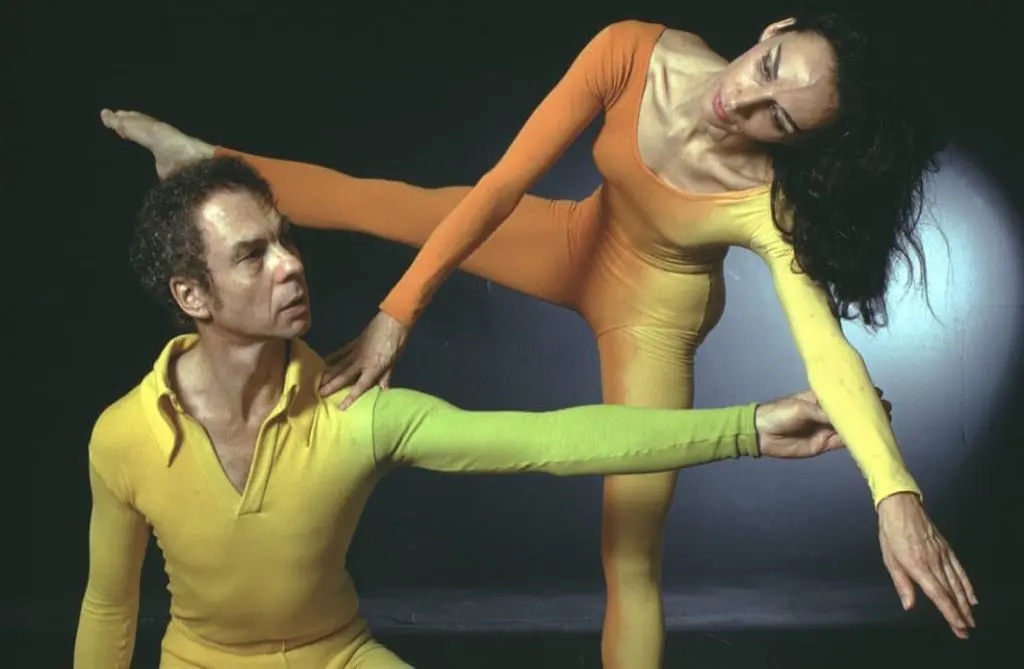

Cunningham never said that he drew upon the content of the three movements of Socrate for his choreography (he was notoriously secretive about such matters). To me, however, the connections seem obvious, although not literally dramatic. Cunningham, the one dancer present in all three movements, represents Socrates. The first movement—a portrait of Socrates—makes sense as a solo. “I stood in one place and did the dancing without moving away from it for about five or six minutes” was Cunningham’s summary of it. This static choreography possibly reflects Alcibiades’ comparison of Socrates to a statue. Based on the texts, it also makes perfect sense to set the pleasant stroll of Socrates and Phaedrus as a duet, and the death of Socrates among his students as a solo with ensemble.

In my view, then, Cunningham would have made Second hand not just to the phrase structure of Socrate but to its overall sound, moods, and content. I realize that this goes against the common view of Cunningham’s way of working, but a story from Carolyn Brown, Cunningham’s partner in the Second hand duet, supports this view. She recounts that, in rehearsal, Cunningham looked “anguished” as they finished their second movement duet. She was worried about him, and confided in Cage. “‘Don’t worry,’ John told me the next day. ‘Merce said it’s at that moment that (Socrates) is preparing to meet death.” Brown tells this story to make her point that “like most of Merce’s dances, I believe, Second hand is deeply meaningful to him.”

Returning to Cheap imitation, I have to think that John Cage would have known what Cunningham was up to, and would have known that Socrate served as the source for Second hand in ways that went far beyond the phrase structure. Satie’s work was deeply meaningful to Cage as well, and no doubt the love for it that he and Cunningham shared was a major reason he had been suggesting this project for over twenty years. Cage introduced the music to Cunningham in a letter from 1944. “Socrate is an incredibly beautiful work,” he wrote. “There is no expression in the music or in the words, and the result is that it is overpoweringly expressive.”

Like Cunningham, Cage would have crafted Cheap imitation to preserve some aspects of Satie’s Socrate that were important to him. I believe that this explains a number of Cage’s choices in the piece.

In the first place, I think that Cage’s choice of modeling Cheap imitation on the vocal line of Socrate tells us something about what Cage (and possibly Cunningham) loved about the piece. Cage’s system works almost exclusively on the vocal line of Socrate, and the choice of registers for the chance-derived pitches mostly keeps the music in the range of a soprano singer. In the 1944 letter, Cage highlights the beauty of the vocal line: “The melody is simply an atmosphere which floats.” Perhaps this is also a preference he picked up from Virgil Thomson, who first introduced Cage to Socrate (the 1944 letter is describing a day with Thomson in which “we must have played and sung [Socrate] six times”). Thomson, in a 1965 lecture, praises Satie’s vocal line, “so sensitive to the sound and meaning of French,” and holds it as the clearest musical treatment of text in European music.

I think that Cage made deliberate choices in the first movement of Cheap imitation that reflect the static nature of the original 1944 solo dance. The use of pedal to create sustained chords out of the flowing vocal line in various places here is one possible example of this. Another is Cage’s choice to omit orchestral motives in various places when the voice is silent. Looking at these motives, they tend to be ones with a fair amount of rhythmic energy, energy that would be out of place with Cunningham’s static dance. Of course, Cage was writing Cheap imitation while out of town, away from Cunningham’s rehearsals, but he would have known the 1944 solo. And who is to say what changes he Cage might have made to Cheap imitation when he reunited with Cunningham for the rehearsals? A detailed analysis of the choreography and the music together might reveal other musical decisions that reflect the importance of particular moments in Satie’s music.

The use of octave doubling in Cheap imitation is completely driven by events in Socrate. In the first movement, a single passage of seven measures at the very end (mm. 168–174) is doubled at one octave and then two octaves. These seven bars correspond exactly to Socrates’ one-line response to Alcibiades in the text: doubling identifies the change in speaker. And in the third movement, Cage doubled at the octave all music derived from the vocal line (as opposed to music from the orchestra line).

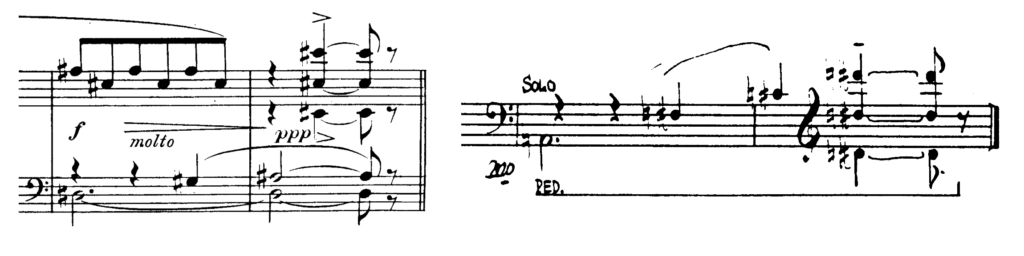

Looking at all three movements, I have found passages where Cage makes exceptional choices—where he chooses to bend or ignore the rules of the system—that seem to come from his attachment to the corresponding moments in Socrate. The ending of the first movement (mm. 175–176) is one such example. In the Satie, the orchestra gradually builds up a D-sharp seventh chord over the two bars from the bass upwards:

Cage makes deliberate choices that mimic this effect. First, he uses the pedal to build up the harmony in the same way that Satie does in the orchestra. Then he makes register choices that match Satie’s exactly. Lastly, he maintains the double octave on the last note. There can be no reason for these choices other than to maintain Satie’s beautiful closing effect.

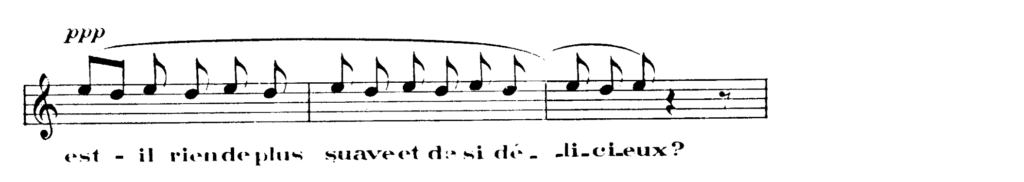

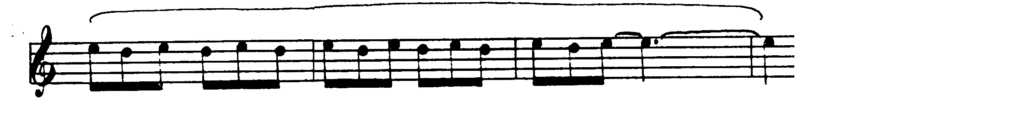

The second movement includes a most interesting exceptional case. There is a simple phrase in measures 182–184 of Socrate that is a slow pianissimo trill on E and D. The text here is Socrates’ expression of joy at arriving at their destination (“is there anything more sweet and delicious?”):

This was one of Cage’s favorite lines in Socrate. He highlights this particular moment in describing the movement to Cunningham in the letter of 1944 (“Socrates and his companion talk about . . . how delightful the air and grass is”). Later, Cage used it as the melodic basis for his composition Sonnekus2 (1985).

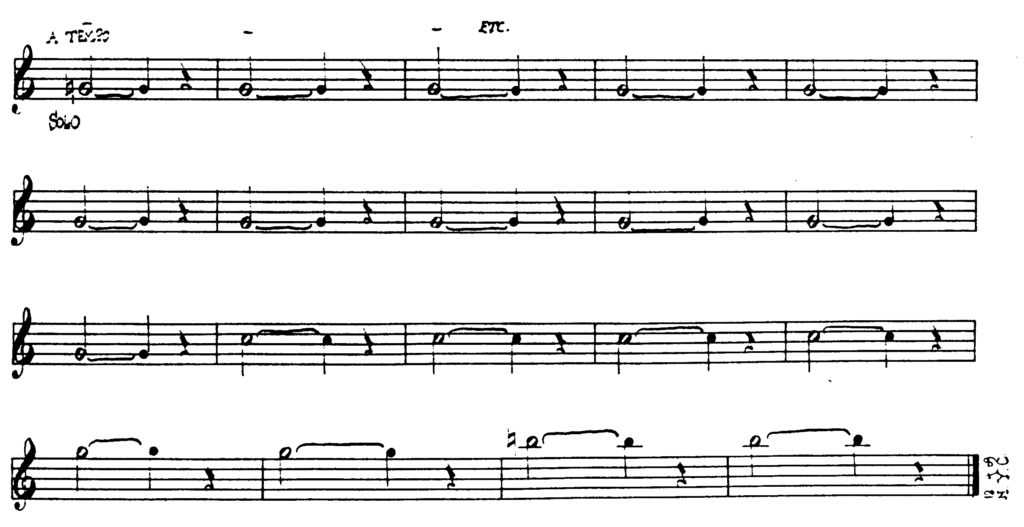

In Cheap imitation, this phrase appears completely unaltered—no transpositions at all:

Knowing Cage’s fondness for this specific phrase, its preservation here raised my eyebrows a bit. How likely is that to have happened by chance, following Cage’s method? There would be five random transposition choices to be made here (one for each halfmeasure) and each would have to match exactly the original pitches: E, D, E, D, and E. Each of those 5 chance operations would have 12 possible results, for a total of 125 possible sequences. That means that the odds of Cage’s chance process leaving his favorite phrase unaltered are 1 in 248,832. It’s possible, of course, but I suspect that this phrase got special treatment.

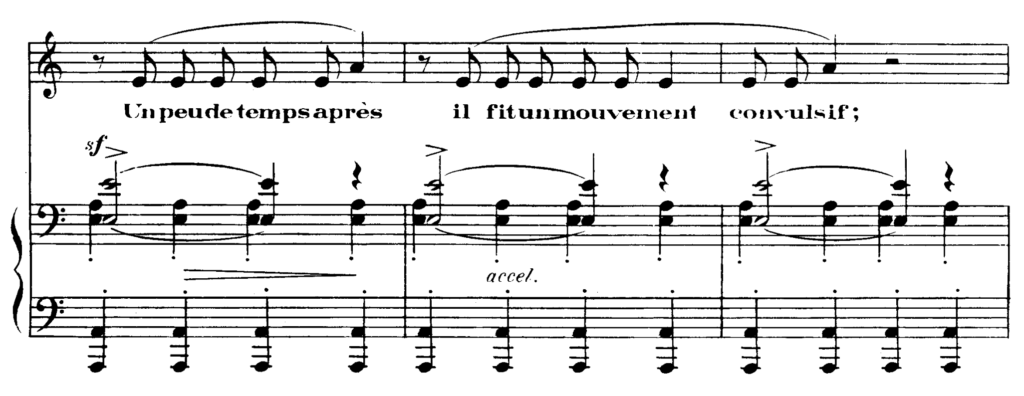

Finally, the closing nineteen bars of the “Death of Socrates” is one of the most arresting and dramatic passages in Satie’s score. Cage responded by making choices to preserve the structure and intensity of this closing. In the Satie, this passage (mm. 276–294) sets the lines following Socrates’ last words. They are delivered in a monotone, with a static, pulsing orchestral accompaniment:

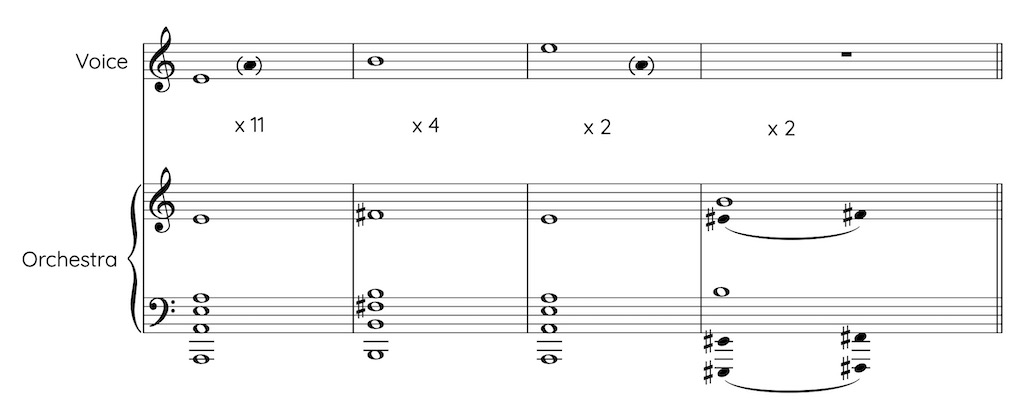

The music stays on this open fifth A/E for eleven bars. It then moves up a step to B/F-sharp for four bars, then returns to A/E for two bars. There follows a closing two bars for orchestra alone based on B/F-sharp in inversion, ending the piece a bit up in the air harmonically. The trajectory of the vocal line mirrors the open fifths of the orchestra, rising up from E to B to E an octave higher.

Cage chooses to set the orchestra music here, not the voice, filling each of these nineteen bars with a single note:

By his system’s rules, Cage should have randomly selected a different transposition every measure, but he chooses to ignore this rule and instead retain Satie’s repetitions. This preserves both the grim simplicity of the music and the 11 + 4 + 2 + 2 duration structure. Beyond this, the transpositions mimic the departure and return of Satie’s harmonic structure: G, C, G, B-natural. The odds of such a structure occurring randomly is about 1 in 16; I suspect that the return to G at measure 291 was deliberately chosen to match Satie’s return to A/E in Socrate. And finally, the choice of register here matches the trajectory of Satie’s vocal line.

Unsurprisingly, Cunningham also highlights the drama of this passage in his choreography. Over the eleven bars starting at m. 276, each member of the ensemble (except Cunningham) begins dancing the same series of steps, until at the end they are all dancing in unison. Then they disperse in different directions over the last eight bars, leaving Cunningham (Socrates) alone on stage.

When I started this re-examination of Cheap imitation, my impulse was to immerse myself in the technical, to dig into the musical mechanics of the piece. And now I’ve wound up right back where I started, describing a love story between Cage, Cunningham, and Satie. Socrate is such a powerful work for both Cage and Cunningham, and Cheap imitation/Second hand really can’t be understood properly without referring back to it. As an experiment, I would love to see Cunningham’s choreography paired with Cage’s two-piano transcription of Satie.

What I hope I’ve demonstrated here is that you can’t just be satisfied with what Cage says about a work like Cheap imitation. You have to dig further into the actual music and see if you can verify that it works the way he says. And then you have to go even further and not be satisfied with just understanding the mechanics of the system, but dig into the motivation for the choices that system represents and for the choices that inevitably occur outside the system. Then Cage’s work comes alive as a meaningful musical experience.

This is part of the series Understanding Cheap Imitation

Notes & sources

My sources for the story of Cheap imitation and Second hand are:

- Merce Cunningham and Jacqueline Lesschaeve, The dancer and the dance (New York: Marion Boyars, 1985), pp. 87–90.

- David Vaughan, Merce Cunningham: Fifty years (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1997), pp. 175–176.

- Carolyn Brown, “Carolyn Brown,” in Merce Cunningham, James Klosty, ed. (New York: Saturday Review Press, 1975), p. 25.

- Carolyn Brown, Chance and circumstance: Twenty years with Cage and Cunningham (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2007), pp. 535–539.

The 1944 letter from John Cage to Merce Cunningham in which he describes Socrate is from John Cage, The selected letters of John Cage, Laura Kuhn, ed. (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2016), pp. 66–67. Interestingly, in an addendum to a letter from Cage to Cunningham just a year earlier, Cage includes the line “L’air est si frais et si délicieux,” which is very close to the text of his favorite line of the second movement of Socrate. It makes me wonder if that passage had a personal meaning for Cage and Cunningham.

The 1944 letter follows a day Cage spent with Virgil Thomson playing and singing through Socrate (“Sometimes I played it while Virgil tortured the air with song”). An idea of this (minus Thomson’s singing) can be had from a recording of a 1965 lecture/performance of Socrate at UCLA.