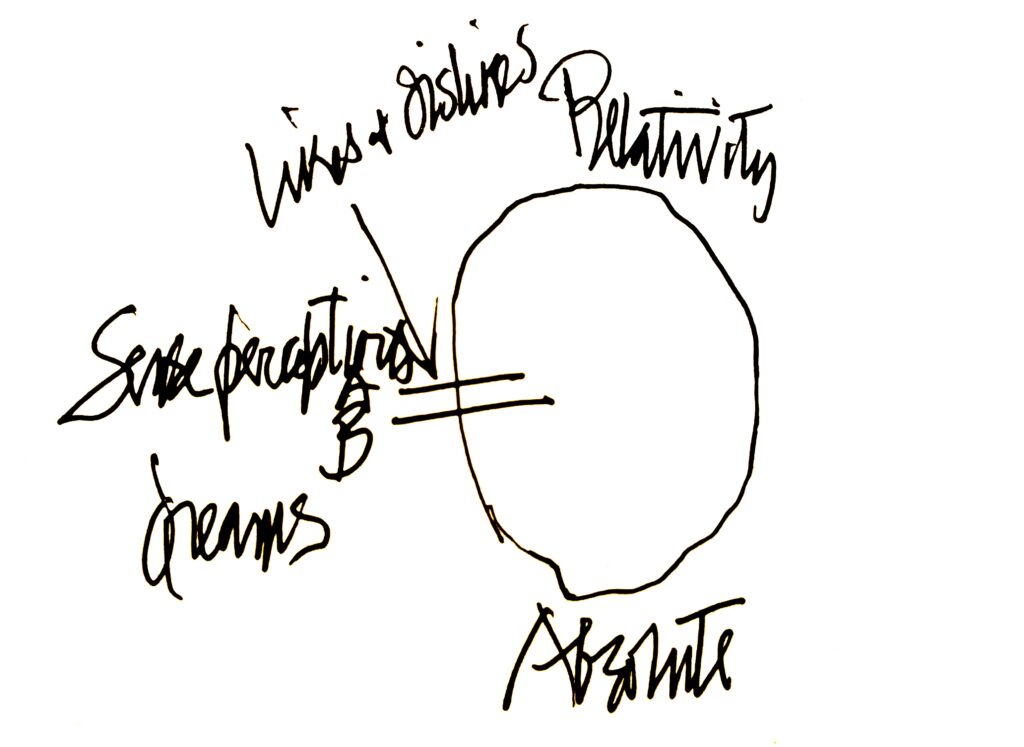

John Cage liked to point to D. T. Suzuki as his teacher on Zen. He often noted that he attended the eminent scholar’s classes at Columbia University in the early 1950s. But what did Cage actually learn there? There was one particular story he told about those classes, the story of a drawing that Suzuki made on the blackboard. Here’s Cage’s reconstruction of it, from an interview in 1979:

And here’s the story that went with it:

He [Suzuki] said, “This is the structure of the Mind, and this (B-A) is the ego. The ego can cut itself off from this big Mind, which passes through it, or it can open itself up.” He said, “Zen would like the ego to open up to the Mind which is outside it. If you take the way of cross-legged meditation, when you go in through discipline, then you get free of the ego.” But I decided to go out. That’s why I decided to use the chance operations. I used them to free myself from my ego.

I must confess, I never fully understood the details of this explanation, just the general idea of getting past the barrier of ego.

Recently, when I was doing research for a lecture on Zen and Cage, I read a passage in the chapter “Zen and Haiku” from Suzuki’s book Zen and Japanese culture that reminded me of Cage’s story about the drawing on the blackboard. Suzuki, in the middle of his discussion of Bashō’s famous poem about the old pond and the frog, takes a little detour to describe the structure of the mind. He says that the mind consists of “several layers of consciousness, from a dualistically constructed consciousness down to the Unconscious.” These layers are:

- Everyday consciousness

- The semiconscious plane, “the stratum of memory” from which we can draw experiences as we need them into full consciousness

- “The Unconscious, as it is ordinarily termed by the psychologist.” It is the place of “memories lost since time immemorial” that arise in times of crisis.

- A deeper layer that Suzuki calls “collective unconscious,” which he describes as “the bedrock of our personality,” and which corresponds “somewhat to the Buddhist idea of ālayavijñāna, that is, ‘the all-conserving consciousness.’”

Being an account of the structure of the mind, it brought Cage’s story to mind. I made a note in the margin for future reference: “Is this something like the picture Cage remembered?”

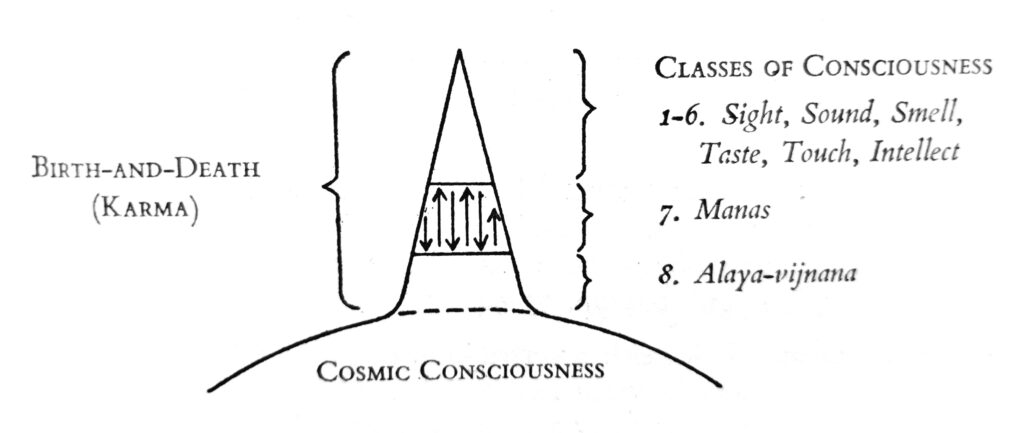

I couldn’t really find any tangible connection, until I saw the following picture in the glossary of Philip Kapleau’s book The three pillars of Zen, in the entry on “consciousness”:

What grabbed my attention was the circle with the gap, here expressed as a triangle emerging from the circle. Could this be related to the diagram that Cage remembered?

Here is Kapleau’s description of the diagram and how it relates to the layers of consciousness:

The above diagram, based on a scheme by Harada-roshi, shows the relation of the eight classes of consciousness to birth-and-death (or karma) and cosmic consciousness. The triangle portion stands for the life of the individual and shows his relation to the cosmos in terms of consciousness. This life is not unlike a wave on the vast ocean; its brief existence seems apart from the ocean—and in a sense it is not the ocean— but in substance it is not other than the ocean, out of which it arose, into which it will recede, and from which it will emerge again as a new wave. In just the same way, individual consciousness issues from universal consciousness and in its essential nature is indistinguishable from it.

The connection between Kapleau’s discussion of consciousness and Suzuki’s is strong. The list of the eight classes of consciousness map onto the four layers that Suzuki describes. The “everyday consciousness” is here split into its five sense constituents, the semiconscious plane corresponds to the intellect, and the unconscious corresponds to manas, which is shown as the connector to the ālayavijñāna, Suzuki’s “collective unconscious”.

Clearly Kapleau and Suzuki are referring to the same model of the mind. Even Kapleau’s inclusion of a “Cosmic Consciousness” underneath it all matches Suzuki. In his essay on haiku, after going through the canonical layers of consciousness, Suzuki says that understanding artistic creativity requires an additional layer, “what may be designated ‘Cosmic Unconscious.’”

Suzuki & Kapleau were both describing the same model of the mind. Could Suzuki have used the same diagram to illustrate it? In that class at Columbia, was Suzuki talking about this particular model and drawing a version of this same diagram? Is this the diagram that was the source of Cage’s memory? I increasingly think that this is what happened.

Cage’s diagram isn’t the same as Kapleau’s, but when he drew it he was remembering an event that took place over twenty years earlier. Certainly there are aspects of Cage’s presentation of the diagram that suggest a connection to these models. The references to “sense perceptions” and “dreams” align with the ordinary and unconscious layers of the Suzuki/Kapleau mind model. The “B-A” ego gap and the idea of it cutting one off from the unity of experience corresponds well with the triangular wave in Kapleau’s diagram. And the notations of “relativity” and “absolute” in Cage’s drawing echo the distinction between “Birth-and-Death” (the everyday reality of life) and “Cosmic Consciousness” in Kapleau’s diagram.

Going back to Suzuki’s essay on haiku, his description of the “Cosmic Consciousness” and the role it plays in creativity is significant:

All creative works of art, the lives and aspirations of religious people, the spirit of inquiry moving the philosophers—all these come from the fountainhead of the Cosmic Unconscious, which is really the store-house (ālaya) of possibilities.

I am struck by how strongly this description would have resonated with Cage in 1952. It directly addresses the spiritual foundation of the creative act, it connects art and religion as being the same thing, and it is all about infinite “possibilities.” These are all themes in Cage’s thinking of the period around 1950. Suzuki’s description meshes well with R. H. Blyth’s presentation of Zen and haiku, and we know that Cage was engaged with Blyth’s writing in the early 1950s. If Suzuki went through this same model in class, it makes perfect sense to me that it would have made a lasting impression on Cage.

Of course, from the perspective of understanding Cage’s musical journey, the details of what Suzuki may have actually described in his class lecture are not as important as what Cage took away from it. What was Cage talking about when he told this story? The 1979 explanation given above is not very clear, but there is another account that Cage gave in an interview in 1977 which goes into a little more detail. First, he said that the “egglike shape” is “the structure of the mind,” and the gap is the ego. He then explained the connection of absolute (below) and relative (above):

And he [Suzuki] said that the ego had the capacity to close itself off from its experience, which went up and out through the senses to the world around us—what we might call the relative world—and then it continued down, to what Meister Eckhart called the “ground” and came back to the ego through dreams.

In this view, the model isn’t a circle with an inside and outside, but rather a circular path up to the conscious sense experience (relative) and down to the unconscious ground (absolute). Cage saw tastes and judgements as breaking this circle. As a result:

One way or another you could be alone or you could be flowing full circle so that you would come out, in the end, in that case, like Rilke looking at a tree and wondering whether you were yourself or were the tree. Suzuki said that’s what Zen would like us to do, rather than use the ego to separate oneself from one’s experience.

In other words, Cage saw the circle as something like an electrical circuit. Ideally, the current flows freely, connecting absolute and relative into a unified experience. But the ego, with its likes and dislikes, cuts off this current like an open switch.

This mind model seems to be unique to Cage; it doesn’t match anything I’m aware of in Suzuki’s presentation of Zen, except in the most general ways. But Cage’s model does mesh well with his own view of the importance of chance as a creative tool. In his 1977 explanation, Cage went on to describe how Suzuki’s lecture influenced him:

This lecture, and other experiences, convinced me that I would take the outward path, rather than the inward path of meditation, since if it was a circle it went all the way around. So my notion then was how to go out through the senses and yet not have any concepts.

You see, you could go in through the dreams or through sitting square-legged [sic] or through deep breathing . . . and you could come to the same conclusion: no concepts.

I can’t really take Cage’s account here at face value. By the time he attended Suzuki’s classes, he had already adopted chance as a compositional tool, so the notion that Suzuki’s lecture led him to this conclusion doesn’t add up. What Suzuki did provide Cage with was a spiritual framework for justifying what he was already doing. And Cage’s own interpretation of the egg-like mind structure as a circular path suits this purpose. It explains why he can claim Zen as a spiritual justification for his work while at the same time ignoring Zen practices. These practices, in Cage’s view, start by going inward to connect to the absolute, and then around the circle to connect with the relative. By using the discipline of chance in his composition, he’s just going around the circle in the other direction—opening himself to all relative experience first, the universe of sound—and realizing the absolute through that process. In Cage’s view, either way has an identical result: “no concepts.”

Looking at all the evidence, my view is that Cage’s version of the drawing is his own creation, shaped from his experience in Suzuki’s classes, but not reliable as an account of what was actually taught. I think that there’s a strong reason to think that what was presented was an account of the eight-consciousness model of the mind, but what Cage took away from it was something quite different.

Sources

The short version of the story, complete with drawing, comes from Maureen Furman, “Zen Composition: An Interview with John Cage,” East West Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, 1979, reproduced in Conversing with Cage, Richard Kostelanetz, ed. (Limelight Editions, 1988), p. 229. The longer version comes from “Time and Space Concepts in Music and Visual Art,” an interview (or possibly a panel discussion?) from 1977 conducted by Richard Kostelanetz. It appears in Time and Space Concepts in Art, Marilyn Belford and Jerry Herman, editors, 1979. The relevant passage is found on pp. 52–53 of Conversing with Cage.

Suzuki’s description of the layers of consciousness is from his Zen and Japanese culture (Princeton University Press, 1959), pp. 242–243.

The diagram of the eight consciousness model and the associated definition of consciousness is found in Philip Kapleau, The three pillars of Zen (Harper, 1969), p. 327. There is a slightly revised version of both diagram and definition in the revised edition (1989). In this revised version, the layer of manas (seventh layer) is more clearly identified as the source of ego: “source of persistent I-awareness.” The “Cosmic Consciousness” is renamed as “Pure Consciousness (Formless Self).”

At the first June in Buffalo festival in 1975, Cage drew that diagram during one of his lectures the first week. The next week, in his absence, Earle Brown referred to it – he may have drawn it again, I don’t recall for sure – and disagreed with Cage’s interpretation. He said his understanding was that Zen was about “charming” the ego into allowing the subconscious to flow in, not merely bypassing it by using chance techniques.