So don’t talk to me about systems, don’t talk to me about aesthetics, don’t talk to me about life, in fact don’t even talk to me about art, and let’s end it with this thought: that it all has to do with nerve, nothing else, that’s what it’s all about; so in a sense it’s a character problem.

— Morton Feldman in conversation with Alan Beckett, 1966

I’ve often made the statement that art is an act of faith. The faith I have in mind is on the artist’s part: the faith in the truth of the work and that one’s mission is to bring that truth to light. I think that my “act of faith” is the same as Feldman’s “nerve”, an inner strength born out of a connection with inner necessity. It is not to be confused with self-confidence, which may or may not be present at the same time. And it is not the same thing as daring or bravado, which is largely a matter of theatrics, the ability to put on the role of the innovator and to project that across the footlights to an audience.

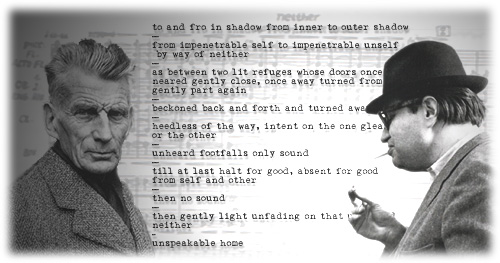

I bring this subject up because I just recently listened again to Morton Feldman’s opera Neither, and was struck by what a colossal display of nerve that work is. Composed in 1977, it features a single soprano and a libretto by Samuel Beckett. It is an hour-long work in which there is no action. There is little text (just 10 lines, 87 words, shown in its entirety in the graphic above), all of which is set in a very simple declamatory style on just a few pitches. Almost the entire piece sits in the four-note range of F to A, inching up even higher to a high D in places. Meanwhile, the orchestra provides textures of living sound, animated from within by changing dynamics and rhythms, sustained over long periods of time. We don’t expect a lot of contrast from Feldman, but to prolong such an extreme sonic image for an hour is thrilling, exhausting for all involved, and required tremendous nerve on the part of the composer.

Of course Feldman had demonstrated nerve before. His first graph piece, for example, was a real step into the unknown, one that gave John Cage the nerve to pick up the I ching and use it to compose music. There are lesser-known, smaller examples, such as the choral work The swallows of Salangan. Here the massed forces hover over the same middle range for the entirety of the piece: eight minutes of dense vocal and instrumental fog. There’s also the astonishing setting of Psalm 144 in Vertical thoughts 5, for soprano, tuba, percussion, celeste, and violin. Written in 1963, Vertical thoughts 5 is remarkably close to Neither both in music and text. Here we have the same stratospheric monotone for the soprano alternating with dark rumblings in the percussion, and the text—”Life is a passing shadow”—could be the synopsis of Beckett’s libretto for Neither.

I could try to make the case that Neither is a breakthrough in nerve for Feldman. Over the years, his works had been getting longer, with the pieces of the mid-1970s reaching a half and hour. But then there’s this jump to an hour with Neither, which crosses some unspoken boundary into a realm where the composer demands our attention in a different way. And Feldman had been working with extreme musical imagery in recent works, especially Oboe and orchestra (1976), but again Neither goes further, staying in these places more persistently. Feldman’s musical vision here is strong and this makes him fearless and demanding.

We in the audience can respond to this in various ways. We can find Neither inspiring, challenging, moving, and mind-changing. For me, there are those moments of edge-of-my-seat attentiveness, waiting for the next word, the next orchestral blossoming. Alternatively, we can deny Feldman’s vision and reject the experience completely. This, apparently, was the response at the premiere in Rome. There is an integrity in this response, I think: a deep-seated objection, quite possibly justified, to such an uncompromising vision. Or we can take the lazy way out and try to find a way to listen from a place of safety, as I think they did at New York City Opera a couple of years ago. They showed some daring for presenting Neither, but then gave it a completely inappropriate, gaudy staging: a stage cluttered with supernumeraries; people going up and down via elevators and wires; shiny multicolored walls, strobe lights and mirrors. The whole production seemed designed to keep us distracted and hence protected from any discomfort that the music or text might cause. City Opera lost their nerve; it was a character problem, after all, just like Feldman said.

Credit: Graphic above comes from an essay on Neither at The modern word.