(This text was written to accompany Mode Records CD 327 John Cage: The works for piano 11)

In June of 1980, Aki Takahashi was preparing to leave Buffalo, New York. Morton Feldman, knowing her reputation as a pianist specializing in new music, had invited her to be an artist in residence at the university where he taught. But now it was time for her to go back to Japan. As a last adventure in upstate New York, Feldman and fellow composer Bunita Marcus planned to take Takahashi on a trip to see Niagara Falls. But the trip was cancelled at the last minute due to the death of Feldman’s old friend, the artist Philip Guston.

At their last meeting, Feldman gave a musical score to Takahashi as a gift. It was a copy of John Cage’s solo piano piece Cheap Imitation with annotations by Feldman. He told her that this was an instrumental version of this piece: flute, piano, and glockenspiel. He signed the title page, just under the original title:

INSTRUMENTAL VERSION (Fl, Pf, Glock)

Morton Feldman

Buffalo, N.Y. Winter 1980

Dedicated to Aki Takahashi

Four different artists were bound up in this single gesture: John Cage, Erik Satie, Morton Feldman, and Aki Takahashi. The story of this gift, a story of memory and connection, unfolds over most of the 20th century.

That John Cage was devoted to the music of Erik Satie is widely known, but the nature of that devotion is not necessarily well understood. Cage almost certainly was introduced to Satie’s music in the 1940s by its ardent promoter Virgil Thomson. While Cage and Satie are usually joined in our minds by their mutual affinities for disruption, it was Satie’s quiet and serious side that was the first guide for Cage in his musical journey. Yes, Satie can be seen as a “clandestine revolutionary” (Alex Ross) or “arguably the most eccentric composer in the history of classical music” (Kyle Gann), but it was not Satie’s brush with Dada that attracted Cage at first. Instead, it was the subtle vocal lines of Satie’s Socrate, a three-movement setting of excerpts from Plato for female voices and orchestra, that entranced John Cage in the 1940s and that ultimately led to Cheap Imitation.

It is not surprising to find this connection arising in the mid-1940s. This is the start of Cage’s search for meaning in music, a spiritual search that would take him to a quieter place than the ambitious futuristic drumbeats of his career in the 1930s. He began to see the value of setting the ego aside, and Satie’s rejection of self-indulgence would have shown Cage a way forward on this path. This statement by Satie, quoted by Cage in 1958, gives us a glimpse of what Cage saw in him:

It (L’Esprit Nouveau) teaches us to tend towards an absence (simplicité) of emotion and an inactivity (fermeté) in the way of prescribing sonorities and rhythms which lets them affirm themselves clearly, in a straight line from their plan and pitch, conceived in a spirit of humility and renunciation.

“Humility and renunciation” are not necessarily qualities we associate with John Cage, but they are exactly what connected him to Satie in the 1940s. In 1948, Cage declared that “beauty yet remains in intimate situations; … it is quite hopeless to think and act impressively in public terms.” He went on to describe how he sympathized with societies that “were interested in music not as an aid in the acquisition of money and fame, but rather as a handmaiden to pleasure and religion.”

Virgil Thomson introduced Cage to Satie’s Socrate and in turn Cage introduced it to choreographer Merce Cunningham. Cage played the music for Cunningham on the piano and Cunningham made a solo dance set to the first movement, following the phraseology of the Satie. This dance, titled Idyllic Song, was premiered in 1944, the same year that Cunningham, with Cage at his side, launched his career as a solo dancer and choreographer.

Cage loved the dance and encouraged Cunningham to choreograph the remaining two movements of Socrate. But the time was not right: Cunningham’s vision was to use multiple dancers, and he had no dance company in 1944. Twenty-five years later, however, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company was the center of innovation in modern dance, touring the world to rave reviews. Needing a dance set to an acoustic musical accompaniment (in order to give the regular musicians and their electronic equipment a break), Cage again raised the idea of finishing the dance to Satie’s Socrate. Cunningham kept his original 1944 solo and created a duet and a dance for the full company for the remaining movements in a similar style.

Cage was supposed to create a new two-piano transcription of Socrate for this dance, but he was unable to get permission from the publisher. Even worse, he could not even get performance rights to use the published piano-vocal score of Socrate. Cage’s creative solution was to make a piano piece that maintained the exact metrical and phrase structure of Satie’s Socrate, but with different notes, thus avoiding copyright issues. He called this piece Cheap Imitation. Cunningham responded by calling his dance Second Hand.

How did Cage manage this feat of intellectual property sleight of hand? First, he reduced Socrate to a single melodic line: he removed all of the counterpoint and all of the harmonies. In this, he was working with the natural strengths of Satie’s original score. The effortless unfolding of the vocal line is the soul of the piece, and Cage’s transformation captures that essence and lets it fill the space of our attention. His reduction almost always uses the vocal line; in a few distinctive places (such as the opening of the third movement) he draws on a melodic fragment from the orchestra. The other transformation he made to the original was to transpose Satie’s melody into randomly-chosen keys and modes. In some places he maintains the melodic shape of the original; in others he distorts it further by shifting individual notes. The rhythms and phrase structure—the essential connection to Cunningham’s choreography—remained untouched.

The result is a piece that is both a reworking of Satie’s Socrate and a profound tribute to it. With its close adherence to the rhythms and contours of the original vocal line, in Cheap Imitation we hear the unmistakable voice of Satie. With its unexpected shifts of color and tone, we just as unmistakably hear the voice of Cage. One can only imagine the joy that Cage felt as he composed this work directly alongside his idol, watching the fluid melody unspool in front of them. Cage had spent the 1960s in a whirlwind of new ideas, new technology, celebrity, travel, and notoriety. Cheap Imitation was a refreshing and reinvigorating return to the deep stillness that had set him on his way in the 1940s.

Audiences in 1970 found the piece shocking. In the context of contemporary music of the time, its simple modal melodies were completely incongruous. Listeners expected provocative random noise from John Cage; this beautiful and quiet gentleness baffled them. Even Cage himself had a hard time explaining it:

Obviously, Cheap Imitation lies outside of what may seem necessary in my work in general, and that’s disturbing. I’m the first to be disturbed by it.

But he also said that “if my ideas sink into confusion, I owe that confusion to love”—namely, his love of Satie.

We can think of Cheap Imitation as a quiet, constantly unfolding conversation between two composers: John Cage and Erik Satie. This, in turn brings us back to Morton Feldman and the many, many conversations he and Cage had during their long friendship as composers. They met when they simultaneously walked out of a New York Philharmonic concert in 1950. The connection here was a love of the music of Anton Webern (they left the concert after hearing Webern’s music, not caring for the rest of the program). Feldman moved into an apartment in the same loft building where Cage lived, and they spent hours together there and elsewhere, discussing music, art, and ideas. As Feldman remembered those halcyon days, “It was great fun, a sort of pre-hippie community. But instead of drugs, we had art.”

Feldman credited Cage with introducing him to many prominent musical and artistic figures in the early years of the friendship. What role Satie played in their long conversations walking around lower Manhattan we do not know, but given Cage’s devotion to Satie, he must have been on the agenda. Feldman did speak highly of Socrate in his 1965 essay “The anxiety of art”:

A piece like Socrate, by Satie, that goes on and on, with very little happening, very little changing, is practically forgotten. Of course, everyone knows it’s a marvelous piece. Every year there’s talk about it, every year someone says, “Yes, let’s do Socrate”—but somehow it isn’t ever done…

Reading this description—”a piece … that goes on and on, with very little happening”—we begin to see the connection between Feldman and Satie. It is something he himself recognized. “My music is between Satie and Debussy,” as he put it to Aki Takahashi.

Feldman met Aki Takahashi in 1979 in Japan and immediately invited her to come to Buffalo. Takahashi had a reputation as a specialist in contemporary music, although she had not worked with Feldman before. What she was perhaps most known for was her performances and recordings of the music of Erik Satie. Together with her husband, composer and music critic Kuniharu Akiyama, she started a series of Satie concerts in Tokyo in 1975, which led to a “Satie boom” in Japan. Takahashi then went on to edit and record the complete piano works of Satie. When she arrived in Buffalo, therefore, Feldman suggested that she feature Satie’s music on her first concert. So when it was time for Takahashi to leave Buffalo, it was her connection to Satie that came to mind for Feldman, and thus his parting gift of the transcription of Cheap Imitation.

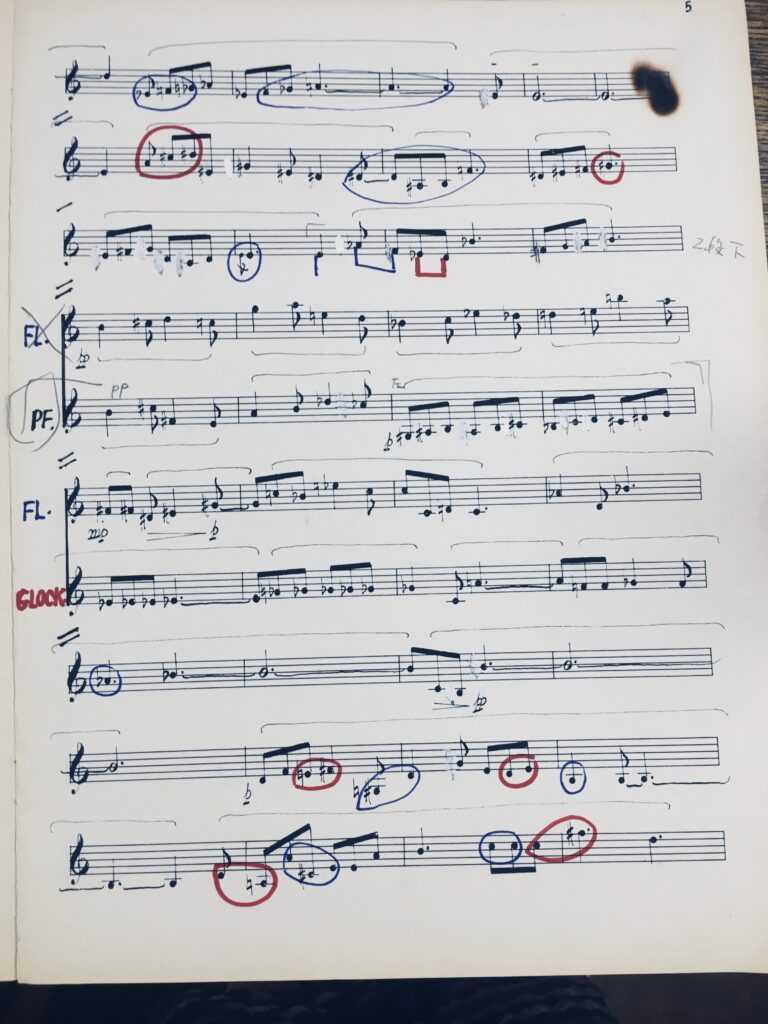

Feldman arranged Cage’s piano version of Cheap Imitation for a trio of flute (doubling on alto flute and piccolo), piano, and glockenspiel. This is the same instrumentation that was used in Feldman’s 1978 Why Patterns? and which (somewhat expanded) was the basis for two of his major works in the 1980s: Crippled Symmetry (1983) and For Philip Guston (1984). Feldman made his arrangement by simply taking the piano score of Cheap Imitation and adding indications about which notes were to be taken by the flute and which by the glockenspiel; unmarked notes were for the piano.

For the most part, the players hand off the melody from one to the other. Satie’s pale monochromatic line passes through Feldman’s prism to produce fragmentary flashes of color. In this regard the sound mimics the physical appearance of the score, where Feldman indicated instrumental changes by colored circles around the individual notes: blue for the flute, red for the glockenspiel. Feldman’s artistry of orchestration brings out little details in the melodic line and changes the mood subtly as the phrases of Satie’s continuous line are preserved or atomized.

At one point in the second movement, Feldman takes two consecutive lines in the score and marks them to be played simultaneously, one on the flute, one on the piano. He thus folds the line of melody in half, turning Cage’s solo line into two-part counterpoint. This was inspired by the layout of Cage’s score: I think Feldman saw those two lines next to each other and recognized that the (unintentional) counterpoint between them would work. After this happy accident, he uses the same technique occasionally through the rest of the arrangement, sometimes with two parts, sometimes with three. These kinds of compositional permutations based on the physical structure of the score are reminiscent of techniques Feldman used in his own compositions. Going from the horizontal (sequence) to the vertical (counterpoint) is a device used in his Piano (1977).

Why did Feldman make this transcription? I asked Takahashi this, but she didn’t know; she was too moved by the gift to ask Feldman any questions about it. She’s even skeptical that he created it specifically for her. After all, it is dated “Winter 1980”, but he gave it to her in June. But I think that Takahashi and her exquisite playing were behind it all along. This is a piece that is tied up with memory and relationship in so many ways. Feldman and Takahashi: we know that he was so inspired by her playing that it became his mental image of the sound of the piano in all his works of the 1980s. Takahashi and Satie: her first concert at Buffalo included some of Feldman’s favorite Satie pieces. The program was suggested by Feldman himself, and there is no doubt that it would have reminded him of how much he loved this music. Satie and Cage: Hearing Satie’s music would remind Feldman of John Cage, of Cage’s devotion to Satie, and how that devotion turned into Cheap Imitation. Cage and Feldman: And thinking of Cage, Feldman no doubt remembered the early days of their own deep friendship, where Satie’s music would have been a topic of conversation. Feldman, Takahashi, Satie, Cage: The transcription of Cheap Imitation brings them all together. It is an intimate party of these artists of exquisite subtlety, all with deep affection for each other.

Cage composed Perpetual Tango in 1984 to be part of a collection of contemporary tangos commissioned by pianist Yvar Mikhashoff. The piece is derived from the “Tango” movement of Satie’s piano suite Sports et divertissements. Cage’s method was to take the rhythm of the original tango and erase parts of it: some notes disappear and the empty space left behind is either filled with silence or the sustaining of a previous note. He does not specify pitches, but instead gives the pitch ranges of the original piece. The pianist chooses which pitches to play in the rhythm given. In 1989 he applied the same procedure on another piece from Sports et divertissements, “The swing”; he titled the result Swinging. Despite the shredding and blurring of the original music, both pieces clearly retain the character of the Satie originals from which they derive. They have the air of ancient music preserved only in fragments, like the poetry of Sappho.

All sides of the small stone for erik satie and (secretly given to Jim Tenney) as a koan is a composition with a completely unknown history. All we have is a page of musical manuscript written in the back of a score of a work by American composer James Tenney with the signature “John” and the date “7/78”. Anything else we say about it is inferred from that page of music. The manuscript was discovered when Tenney’s papers were being organized after his death. It has been attributed to Cage, but the handwriting doesn’t look at all like his and the stylistic connection to Cage is weak. Neither Cage nor Tenney—nor anyone else, for that matter—said a word about this piece, so unless some witness steps forward its composer will remain a mystery. It consists of a single repeated measure of chord changes and a modal scale. Unlike any Cage piece I can think of, there are no instructions about what to do with these simple materials, clearly derived from Satie’s Gymnopédies. Whoever wrote this, there could be no better interpreter for it than Aki Takahashi, a pianist who has a deep understanding of Satie’s music and who has the creativity to work with an open-ended score.