I’m interested these days in the connections between Morton Feldman’s music and the music of other composers, a network that can be explored through playing the piano. Aki Takahashi got me thinking about it when we spoke in Buenos Aires in September, and there are plenty of examples in Feldman’s writings about music. Unlike many other late-century composers who distanced themselves from earlier composers, Feldman encouraged connecting his work to the Western musical tradition, even though those connections can seem elusive at first glance.

The latest music to migrate from the bookshelf to the piano to be worked on are pieces by Feldman and Beethoven. For the Feldman, I’m taking a break from the long, late pieces for a bit and looking at small things from the 1950s: Intermission 6 again (1953), and Piano (three hands) (1957). And, having given up my copy of the Beethoven sonatas for lost, I bought a new copy from Dover and have started working on the Sonata in D, Op. 28, the “Pastoral”. What I’m finding is that these pieces are talking to each other—or at least Feldman is speaking to Beethoven—about voicing, weight, and sound.

As you may recall, Intermission 6 consists of a number of scattered sounds with the instruction to play them in any order, holding each sound until barely audible. One of the things I’ve noted about playing this is an increased awareness of the spacing and hence weight of the different sounds. Some are single notes; some have two, three, or four notes. The spacing of these makes a big difference to the perceived density of sound. One of the technical issues in playing this is to get the balance of the different registers just right. Getting into the natural rhythm of the sounds arising and passing away, my attention becomes more focused on factors like this.

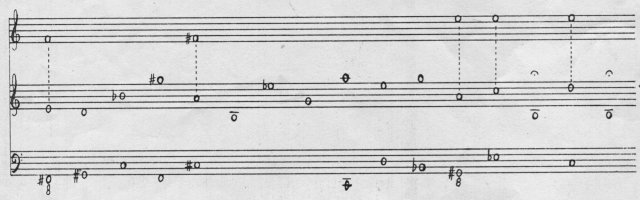

Turning then to Piano (three hands), I started to pay attention to the spacing there. This piece is two pages of rhythmically undifferentiated sounds, also from one to four notes at a time. What I realized is that the spacing here is uniformly wide, which is why the “third hand” is needed: the spans are way too wide for even a large hand like Feldman’s (or mine). Here’s a bit of the score (note that the top line is written two octaves below sounding pitch):

The identity of this piece is bound up with the sound of the spacious sonorities here: very open and airy, not dense at all (the smallest interval within any chord in the entire piece is a minor sixth). Small changes to the arrangement of a chord make a difference, not only in the pitch content of the harmony, but to the weight and feel of the sound. Towards the end of the system above, the three E’s in the top line tend to group those three chords together, so I hear the differences between them more clearly. Even the subtle shift between the last two, where the space between the lower lines opens up from an octave-plus-sixth to over two octaves, makes a noticeable difference in density. By keeping the dynamics and rhythms so flat and unchanging, Feldman makes these subtle modulations of weight more apparent.

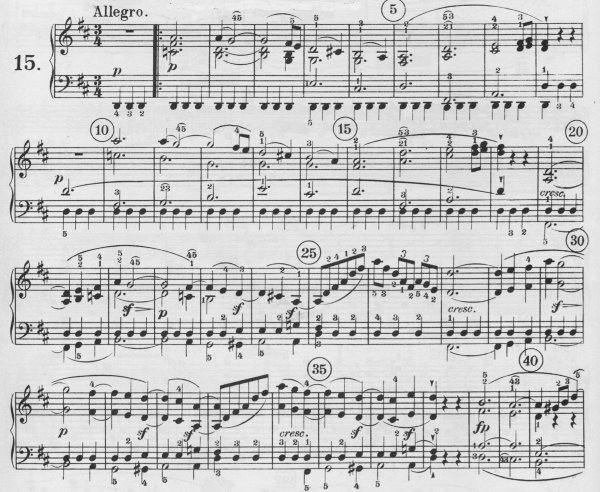

So then I start learning the first movement of the Beethoven Op. 28, which certainly looks like a totally different animal:

Beethoven states the same 10-bar theme twice. But what I keep hearing is the difference in sound between these two statements. The first is dense and low; the second is an octave higher, but the voicing is also more open throughout. The tune and its harmonization are exactly the same in both statements, but the first sounds heavy and dark, while the second rises up lighter. The effect is not unlike dawn, I think. Beethoven does the same thing with the next phrase, also repeated. The first time is low and dense; the repetition takes the right hand up an octave and drops the inner voice, opening up the texture.

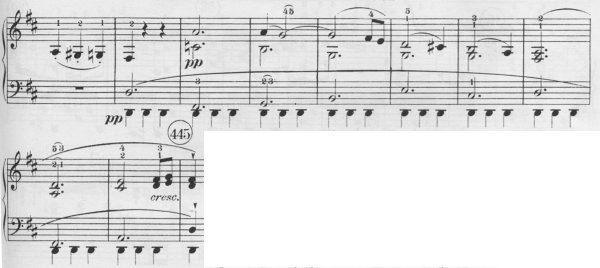

This same theme appears in the coda. Here the more open voicing is used, but this time in the lower octave. It’s a third, completely different setting of that phrase:

I started hearing the changing weights of sound all over in the piece. It’s beautiful to listen to this music with this perspective, but awful to try to write about. We just don’t have good language for this dimension of music, and no good strategies for saying anything terrifically useful about it (at least not that I know of). But maybe just noticing it is sufficient; perhaps there are places analysis just doesn’t work very well. What would it mean to have aspects of music that were outside analysis? Does it mean that we can’t write about it at all? Or is it a different kind of intelligence that’s encouraged here?