This week’s mail brought the new recording of John Cage’s The ten thousand things from MicroFest Records, and a beautiful thing it is. The ten thousand things is the collective title for a set of five pieces that Cage composed in the mid-1950s. The pieces share a common underlying time structure, general compositional approach, and titling convention. Their individual titles express just the duration of the piece (calculated down to the ten-thousandth of a second) and performer required:

- 31′ 37.9864″ for a pianist

- 34′ 46.776″ for a pianist

- 45′ for a speaker

- 26′ 1.1499″ for a string player

- 27.10.554″ for a percussionist

“The ten thousand things” is a phrase representing the diversity of the creation that one often encounters in Taoist writings and similar sources. Cage’s concern in the early 1950s was how to create compositional procedures that would embrace the wide universe of sound; how to compose in a way that would allow a great diversity of musical events to arise spontaneously from the underlying creative power of silence. This set of pieces was the culmination of his initial chance music, a final expression of what he could do with sounds tossed into rhythmic structure by chance.

In keeping with the motivating idea of abundance, Cage intended that these five pieces could be performed simultaneously in any combinations. The MicroFest CD presents all five at once. Vicki Ray and Aron Kallay are the pianists, Tom Peters is the string player (double bass), and William Winant is the percussionist. The speaker is John Cage himself, via a 1962 recording of his delivery of 45′ for a speaker (there’s also a bonus track with Cage’s introduction to the talk). The performers do a wonderful job: these are very challenging pieces to play. There is a lightness and clarity in the playing that is both completely appropriate and refreshing here, not the kind of sweaty bang-you-on-the-head style that is common among some virtuoso new music performers. The performers stay out of the way and allow the bewildering diversity of musical events arise, change, and pass away continuously in front of our ears.

But the truly remarkable accomplishment of the MicroFest release is the little device tucked in with the CD booklet.

It’s a USB memory drive on which is an application (designed by Aron Kallay) that presents an alternative way to experience The ten thousand things.

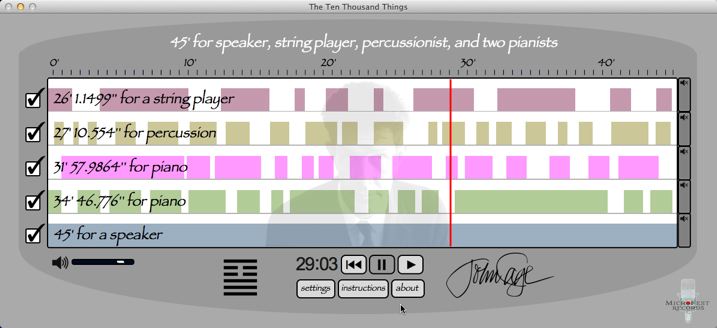

You select the pieces you wish to hear performed simultaneously, then set it off. The program makes a random rearrangement of the component parts of the selected compositions. The longest piece selected becomes the overall duration of the generated performance, and the application shuffles the chunks of the other pieces and inserts silent gaps to spread them all out over this duration. This is in keeping with Cage’s instructions for performance: “Any amount of this music may be played or not and in any combination (vertical or horizontal) with other parts written (for a pianist, for a string player) or to be written.” I particularly like versions with plenty of gaps in them (as shown above), which result most often when you use 45′ for a speaker as the longest piece in the mix. It can be beautiful then to mute some of the parts and get a very spacious duet for pianist and percussion, for example.

This is the ultimate realization of what Cage envisioned with this piece. His idea was for it to be forever a “work in progress”, an ever-growing collection of materials from which an endless variety of performances could be made. As he described it in a letter from 1953:

From time to time ideas come for my next work which as I see it will be a large work which will always be in progress and will never be finished; at the same time any part of it will be able to be performed once I have begun. It will include tape and any other time actions, not excluding violins and whatever else I put my attention to. I will of course write other music than this, but only if required by some outside situation.

Thankfully, Cage didn’t follow through on his vision of working on this piece for the rest of his life. MicroFest’s The ten thousand things program gives us a glimpse of that expanding universe of musical combinations, though. Even though John Cage was notoriously averse to recordings, he would nevertheless have loved this. He would have found it, as I do, a marvelous realization of what he was aiming at fifty years ago. An interactive computerized version of The ten thousand things is the fulfillment of a dream he didn’t even know he had.

On a personal note, it is also kind of a fulfillment of a dream of my own. It has been almost thirty years since I studied Cage’s notes and manuscripts for these pieces and teased out of them the method of their composition. When I did my dissertation, I did some computer-assisted simulations of Cage’s compositional process in order to validate my findings (I composed an extra minute or so of the string piece). I was fascinated by computers and using them to realize Cage-like chance music. The computerized version from MicroFest is exactly what I would have loved to have done then, and it delights me no end to see it here today.

I’m so happy to learn of these recordings. Thanks for this wonderful post. Can’t wait to listen!