[This is part of the series Opening the door into emptiness]

At the end of January of 1951, John Cage began composing the third and final movement of his Concerto for prepared piano and chamber orchestra. He had a copy of the I ching, the ancient Chinese oracle book, a gift from his student Christian Wolff. He had three coins, some blank music manuscript paper, and a pencil. He also had a chart of 224 individual sound events scored for piano, orchestra, or a combination of both, arranged into sixteen rows (lettered A-Q) and fourteen columns (numbered 1-14).

He began with the first phrase: three measures. He consulted the I ching by tossing the coins six times to determine the six weak (yin) or strong (yang) lines that made up the primary hexagram for the first measure.

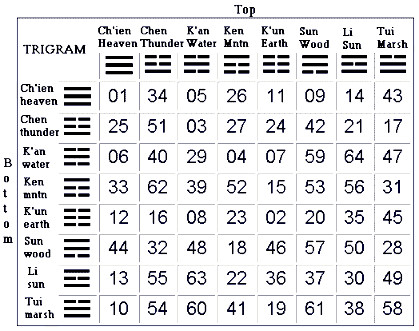

He looked up its number in the book: 57. According to the coin toss, the third line from the top was in motion, changing from yin to yang, and so a second hexagram appeared: number 44. First measure: 57 and 44. Cage repeated the process for the next two measures: 64 and 35; 12 and 31.

He then translated these numbers into sounds and silences. The odd numbers meant silence. The even ones he converted to simple moves, down-and-across, made on his chart of sounds. 57 was a silence; 44 translated to a move of down five, over one. He wrote down the results on his manuscript paper, using letters and numbers to identify the cells on the chart:

Silence F2 M5 Silence N6 Silence

He continued, tossing coins and discovering hexagram numbers for the two measures of the next phrase, and then the four measures of the phrase after that: 53, 52, 42; 1, 31, 28, 7, 24, 62, 34. The lengths of the next three phrases inverted the order: four, two, three. Cage reused the numbers for the first three phrases, but inverted their meaning: odd for sound, even for silence. The list of silences and sound chart cells grew:

Silence D7 I7

Silence Silence L8 Silence N11 E13 I13

E7 H10 Silence H13 Silence Silence Silence

E7 Silence Silence

H1 Silence Silence L2 Silence O5

Now he began writing out the actual music. He put in rests for the silences, and transcribed the contents of the appropriate chart cell for the sounds. There were no other decisions to make. The music began appearing one sound, one silence at a time.

John Cage had now passed through the doorway opening onto a new world of music. This was a new way of working for him, different even from what he had done in the previous two movements of the concerto. There, sounds had been chosen by arbitrary moves on the charts, but he had acted as a composer, arranging the sounds into a particular continuity. Here, he composed from a place of stillness. As he stood silently by, the continuity of sounds was composing itself for him. This was a direct experience of emptiness itself, of saying nothing, of needing to do nothing, of just hearing the sounds as they had come to be at that moment.

This was a defining moment for Cage as a composer. He used chance (and specifically the I ching) to compose practically every work for the remaining 41 years of his life. This was a musical experience, a compositional experience, but it was also every bit as much a spiritual one.

I have written often on Cage’s compositional journey, both leading up to this moment in 1951 and leading away from it. In this series, I will take up the spiritual journey that was inextricably bound up with the musical one. He traveled this path during the decade before the breakthrough of 1951. It combined the ancient and the modern, East and West, traditional views of art and avant-garde ones, the impersonal and the personal. To understand his taking up of chance you have to understand this journey, and to fully understand the journey you must be able to see it as a journey into both musical silence and inner silence.

The story of Cage’s spiritual turning follows a common sequence: ambition, disillusion, doubt, the search for meaning, wisdom. The primary source for the first part of the story is Cage’s lecture “A composer’s confessions” (1948). In it, he is unusually open about his emotional state in the 1940s. He describes his quest for a purpose for music, which for him was identical to a purpose for his life. He finds that purpose—the oft-cited “to quiet the mind making it susceptible to divine influences”—but still cannot reconcile a traditional spiritual view with his contemporary role as an avant-garde musician.

To resolve this dilemma, he turned from a study of religion and philosophy to the pursuit of music composition as a path to wisdom. Over the three years 1948–1951, Cage wrote a series of lectures, articles, and compositions that explored the relationship of law and freedom. These outline what I think of as “the way of experimental music”: using systematic methods of composition as a form of renunciation leading to liberation. This was a gradual discovery for Cage. At the end, it was Morton Feldman who pointed out the door that Cage had been seeking all this time, the door through which he stepped in 1951 with his book, his coins, his pencil and blank paper.

Read the next post in this series: 1 — Confessions (1948)

Sources

The description of the composition of the third movement of the concerto is based on the manuscript worksheets, which were in the possession of David Tudor (and are now at the Getty Research Institute). For a detailed account of the manuscripts and the process of the last movement, see my dissertation The development of chance techniques in the music of John Cage, 1950-1956 (New York University, 1988), pp. 73-87.

The six hexagram numbers thrown for the first phrase are not given on the worksheet and I did not include them in my account in my dissertation. I derived them from the known moves on the chart, speculating that Cage started his moves at cell A1.

The drawing of the hexagram is my own, not Cage’s. The chart of hexagrams shown here is not the one Cage used, but certainly quite similar.