Triadic memories, like all late Feldman, is a series of repeated patterns, musical images that are extended in time by repetition. Repetition also functions over a larger scale, working with memory: “Oh yes, here that comes again.” In some pieces these repetitions are of larger chunks of music, with a system, set of systems, or even pages of music reappearing, often with permutations.

I’ve always thought of these larger-scale repetitions in terms of the whole pattern: pitch and rhythm together. Playing through Triadic memories, I’ve become aware of them rhythmically, repeating even as the pitches are moved around. Here’s an example of two systems of music (nine measures each), that establish a pattern that will reappear over the middle third of the piece.

Taken at the measure-by-measure level, there are only a handful of patterns used here: the same half-a-dozen permutations of dotted eighths, eighths, and sixteenths (either regular or within quadruplets) that have dominated the entire piece so far. In the beginning, the arrangement of these, together with the unusual placement of the repeat signs, creates a sort of hemiola effect: the first fifteen attacks occur at regular dotted-eighth quadruplet intervals.

This somewhat complicated way to notate straight dotted eighth notes, while theoretically not having any audible consequences, nevertheless has affects me as a pianist. I’m mentally carrying along the patterns defined by the bar lines, even as the constant dotted-eighth-note rhythm is overlapping the bars. Those rests at the starts of measures 353 and 354 suggest a kind of lift, which weakens the following attacks and makes for subtle differences between them and the attacks that occur on a downbeat.

The placement of rests at what would otherwise be the strong part of a bar is a phenomenon that occurs extensively in Triadic memories and in Feldman’s music in general. In the last part of the example above, when the rhythm turns to regular dotted eighths (not quadruplet ones), The rhythm extends to an entire measure between attacks in measures 365–68, but with the attack coming on the second half of the bar. Besides softening the attack, it also creates the lovely rhythmic effect at the repeat sign of shifting unexpectedly back to attacks every half-measure, thus concealing the repeat.

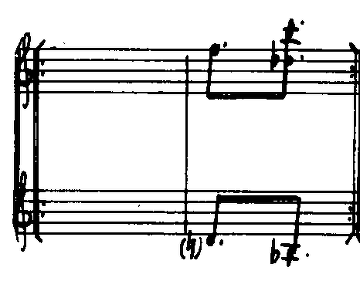

Elsewhere in the piece this principle of weakening attacks by placing them in weak rhythmic locations occurs at the scale of the entire measure. How can I explain the psychological difference between this, a two-bar phrase consisting of a pattern and a measure of rest:

And this, a two-bar phrase consisting of a measure of rest and the same pattern:

I can’t explain it, really, but I do know that I think the pattern differently when I put the measure of rest first. This is the sort of thing that Feldman was referring to, I think, when he wrote about “notational images” in his work:

Though these patterns exist in rhythmic shapes articulated by instrumental sounds, they are also in part notational images that do not make a direct impact on the ear as we listen. A tumbling of sorts happens in midair between their translation from the page and their execution. (“Crippled symmetry”, 1981, reprinted in Give my regards to Eighth Street, p. 143)

I feel this “tumbling” as the playing out of a particular kind of engagement between Feldman as a composer and me as a performer. The energy of this engagement is the life-breath of playing Triadic memories.

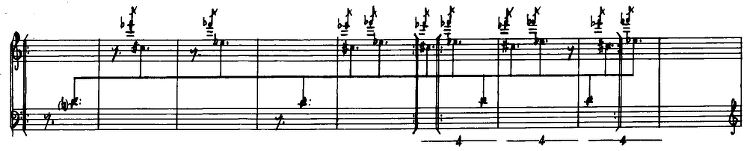

There is a larger structure of rhythmic patterns here as well. Each of the two systems is a self-contained unit of nine measures (this is an example where the manuscript score is essential to understanding Triadic memories, like all of Feldman’s late works). Immediately following this, at the top of the next page, the rhythms of these two systems repeat exactly, even though the pitches are slightly different. This second time around, Feldman interpolated a system that forms a third rhythmic block in between the two we’ve already heard:

As an additional modification, the repeat signs are omitted from the first system.

Two pages later, after a few other images have arisen and disbanded, the three systems of this passage resurface. Feldman rearranged the blocks this time: he swapped the first two systems (putting the repeats back into the first one) and reversed the third one:

Here the pitches do not change between the two appearances, but the rearrangement of the blocks confuses my memory of how this all went together before.

The musical patterns of this passage have other descendants that appear in these same pages of Triadic memories. Some of these use the same pitches in similar, but slightly different patterns. Others maintain only a vague resemblance to the motion and rhythms of measures 352–369. The last appearance of a part of this specific pattern occurs a good deal later in the piece, when that reversed variant of measures 388–396 shows up again, this time embellished by high grace notes:

The grace-notes and dotted-eighth rhythm spin off into a new pattern after this, ultimately bringing in the grace-note chord image whose history I have discussed elsewhere.

Note: Audio examples are taken from Aki Takahashi’s recording of Triadic memories.