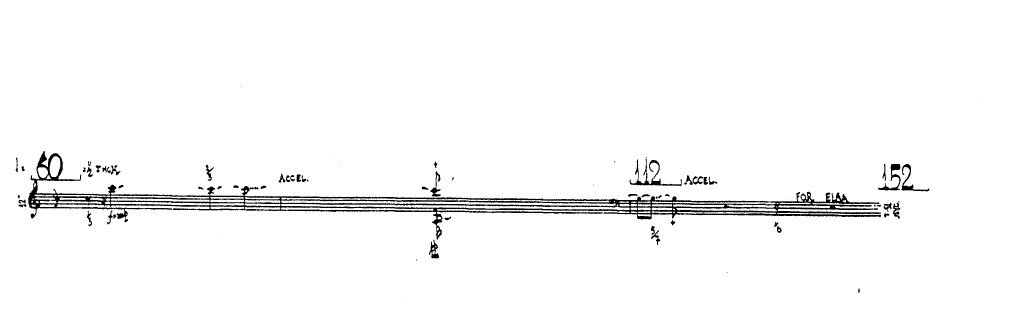

The second of Cage’s silent pieces is the one that everybody has heard of: 4′ 33″. The basic facts of the piece are well-known. Composed in 1952 and premiered in Woodstock, New York on August 29th of that year, it consists of three movements: silences with durations of 30”, 2’ 23”, and 1’ 40”. David Tudor performed the piece at its premiere. He sat at a piano with a stopwatch. He closed the keyboard lid to indicate the start of each movement and opened it again to indicate the ending. This was Tudor’s solution to the problem of how to make it clear to the audience that there were three movements and not just one continuous silence. Those are the essentials of the history of 4′ 33″. What I want to focus on here is the actual composition of the piece itself—how Cage actually created the piece with those durations—and Cage’s own attitude towards the piece and the response it generated.

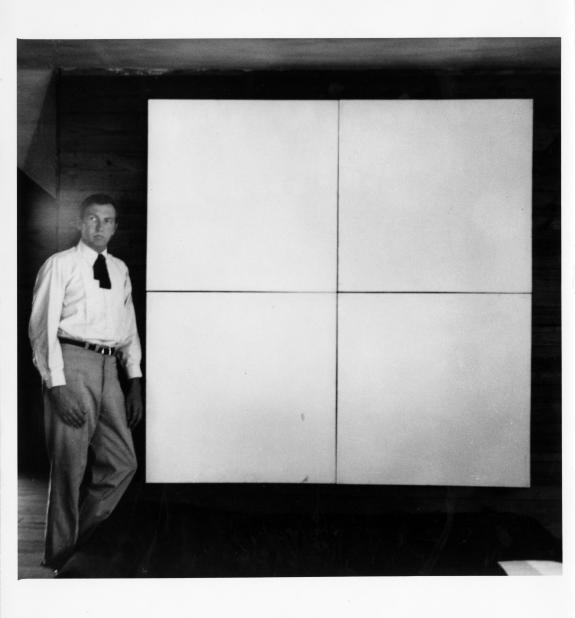

But first let me take up the question of “why now?”: Why did Cage write a silent piece in 1952 after having first thought of it at least four years earlier? Cage himself suggested two factors that played into his decision. The first were the all-white paintings of Robert Rauschenberg, created in 1951. He stated in an interview that “what pushed me into it was not guts but the example of Robert Rauschenberg.” Seeing the white paintings, he felt compelled to make the musical equivalent, to keep music abreast of the developments in visual art. The other event that Cage mentioned was his experience in the anechoic chamber at Harvard. As the story goes, he went there to experience complete silence and discovered instead that he continued to hear sounds created by his own body. This led to the profound realization that silence is not the absence of sound, but rather the absence of intentional sound.

These events—especially the Harvard visit—are sometimes portrayed as breakthrough, “eureka!” moments that sent Cage straight to his desk to write 4′ 33″. But as we know, Cage actually came up with the idea of a silent piece at least four years earlier, without reference to either Rauschenberg or an understanding of silence as being unintentional sound. This original conception of a silent piece, as I wrote in the last installment of this series, came from an interest in what I have called “compositional silence,” the relinquishment of self and self-expression in composition. Silent prayer, the original silent piece, was to be a strongly anti-materialist gesture that would be the fruit of this inner work of silence.

Cage did, in fact, do this inner work between 1948 and 1951, as he pursued different disciplines that quieted his compositional voice. The end result was his achievement of compositional silence through the use of chance operations in the last movement of his prepared piano concerto. Cage was working on silence in his life and work during the years between Silent prayer and 4′ 33″, but in a completely different direction than that implied by a piece entirely made out of silence. As he was caught up in “praising silence” through his works of 1948–1951, he appears to have dropped the idea of Silent prayer altogether. There is no mention of it anywhere in his writings and interviews after 1949. It doesn’t even appear in his 1950 “Lecture on nothing”—as obvious a place for a silent piece as one could imagine. Pursuing compositional silence appears to have dampened his interest in composing a piece made of silence.

The role of these two experiences, of Rauschenberg’s white paintings and the Harvard anechoic chamber, served more to bring the silent piece back to the forefront of Cage’s thinking than to inspire 4′ 33″ directly. The insight gained at the anechoic chamber, in particular, was important for the appearance of 4′ 33″ at this time. What it did was to give Cage another way to express his understanding of the power of non-intention, of letting things happen rather than making them happen. Cage had fully embraced chance operations in his music and was fully committed to this compositional silence. Now he had a way of relating it to the physical, acoustic realm. His aphorism “there is no such thing as silence” served to turn the equivalence of silence and non-intention from an inner experience into an outer experience, something that could actually be made concrete and shared. So long as silence was a purely inner knowing of emptiness, a silent piece was nothing more than a symbol for this ineffable knowledge. Once silence became something that could be listened to, a silent composition had a reason to exist and seemed possible.

There is another factor that I believe precipitated the creation of 4′ 33″ in 1952: Cage now had the technical means to compose a piece made out of silence. In fact, ever since he began using chance techniques in 1951, Cage’s compositional processes were leading him towards more and more silence in his music, and it perhaps was just a matter of time before a completely silent work appeared. One of the important breakthroughs in the prepared piano concerto was that sound and silence were compositionally equivalent and interchangeable. Cage was, for the first time, composing with silences as much as he was composing with sounds. Chance operations tangibly revealed to him the way that time structures could be considered as empty, silent spaces in which any sounds could appear at any time: “Composition becomes ‘throwing sound into silence’”, as he explained it to Pierre Boulez.

As a result of this development in Cage’s compositional approach, silence began to take on a much more prominent role in his music. Prior to 1951 his music actually has relatively little acoustic silence in it. The few exceptions to this are dance pieces, in which the silences were most likely tied to the dramatic needs of the choreography. But in even the very first chance composition, the last movement of the prepared piano concerto, the continuity is for the most part evenly split between silences and sounds, with the last, five-measure phrase of each structural unit deliberately left silent. This trend towards longer, more structural silences continues in the chance works composed in 1951 and 1952, with an extreme example in the piano piece Waiting (1952), which is silent for almost the entire first half (this is another dance commission, however, so it is not clear whether this silence was due to chance operations or dramatic choice).

The possibility of structural silence was always present with Cage’s first chance systems. It was even possible that rather lengthy silences could occur. In Music of changes, for example, even though the music is often quite dense and active, there are entire phrases that are nothing but rests. These occur because, during the compositional process, Cage’s coin tosses resulted in a string of even-numbered I Ching hexagrams, indicating silence. That his chance operations would result in complete silence was a very real possibility for Cage, one that was always lurking as he tossed coins and made lists of hexagram numbers.

If the composition was short enough, it could even happen that the entire work would be silent. This brings to mind Cage’s Seven haiku of 1951–52. These were short pieces for piano that Cage wrote at the same time that he was making the monumental Music of changes. The Haiku used the same method and charts as Music of changes, but to create tiny miniatures. The structure of these pieces was a mere three measures long, with beat pattern of 5–7–5 (matching the syllable counts of haiku). Because of the tiny scale of these pieces, the probability increases that a purely silent Haiku could result. Indeed, the first of the Seven haiku contains only two sounds.

What if a coin had flipped differently here or there and those numbers had been even (selecting silences) instead of odd (selecting sounds)? Without Cage even meaning to do it, a silent piece would have appeared. Is 4′ 33″ (or some part of it) the “Eighth haiku?” Even if this specific turn of events didn’t happen (and there is no way to prove or disprove it), it is certain that Cage was aware of the possibility through his immersion in the Music of changes/Seven haiku process. Composing silence was something he was doing every day, and this silence was, at times, taking center stage.

So it was a combination of factors that all came together in 1952 to prompt Cage to compose 4′ 33″. The encounter with Rauschenberg’s white paintings brought the dormant idea of a silent piece back to the foreground of his thinking; it set an example of what would be seen as a daring gesture. The contemplation of silence in the anechoic chamber at Harvard opened his mind to a new way of integrating acoustic and compositional silence, a view that equated listening to ambient sound with following chance operations. And those chance operations themselves provided the technical means to create the work, perhaps even producing something like it entirely by the accident of the coin tosses.

There was one other critical factor that came into play: the encouragement of David Tudor. While Rauschenberg’s example, the nondualistic view of silence-as-sound, and the compositional technique were all necessary and all lead towards a silent piece, it was the purely practical matter of composing a piece for a concert that made it happen. John Holzaepfel describes the scene when Cage told Tudor about possibly composing a piece made of silence.

If it was the implications of Rauschenberg’s radical act … that emboldened Cage to begin composing the piece, it was Tudor’s interest in performing it that persuaded him to finish it. When the composer expressed doubts about presenting, as a serious work of music, a chance-generated sum of silences, the pianist replied that he hoped Cage would complete the composition in time for a recital he was planning to give in Woodstock, NY, at the end of the month.

In the end, for all the spiritual and musical investigations into silence that he pursued in the four years between Silent prayer and 4′ 33″, Cage behaved as any professional composer would: he wrote his silent piece because a performer asked for it. In my next installment, I’ll investigate exactly how that composition took place.

Next in this series: The composition of 4′ 33″

Home page for the entire series: John Cage’s silent piece(s)

Sources & asides

Kyle Gann’s No such thing as silence (Yale University Press, 2010) has an extensive account of the creation of 4′ 33″, including the tricky matters of chronology regarding Cage’s visit to the anechoic chamber. The “guts of Rauschenberg” quotation is from a 1973 interview with Alan Gillmor and Roger Shattuck (excerpted in Richard Kostelanetz’s Conversing with Cage, p. 71). John Holzaepfel’s description of Tudor’s role in the creation of 4′ 33″ is in his article “Cage and Tudor” in The Cambridge companion to John Cage (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

It is only recently that I noticed that Silent prayer is not mentioned in “Lecture on Nothing”, and that I realized this might be significant. If you read this lecture looking for a mention of a silent piece, it becomes clearer that it really ought to be there somewhere. That it does not appear can only mean that the idea of Silent prayer was no longer top-of-mind for Cage by 1950. It’s not just that Silent prayer was never realized, he actually abandoned the project, no doubt because chance filled the role that he originally imagined a musical silence would. I find these kinds of insights interesting: the ones that rely upon something not happening.

There is a beautiful description by Cage describing the compositional process of 4’33” seen in Peter Greenaway’s Cage volume of his 4 American Composers. He is asked, by an audience member at Harvard (during his Norton Lectures), about the piece. He said he composed it by small units of time. Adding them together, but filling the time units with silence. In the end, he smiles and genuinely suggests that “I may have made a mistake” in adding up the time units.

That’s right, Paul. Much more on that in next week’s installment!