In 1989, the Inamori Foundation in Japan announced that they were awarding that year’s Kyoto Prize in Creative Arts and Moral Sciences to John Cage. The award citation portrayed Cage as “a prophet who has foretold the spirit of the coming era”, transforming “all European music into the past tense.” This was just one of the awards and honors Cage received after reaching the age of 75 in 1987 (he was named the Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University in 1988, for example).

Surprisingly, the Kyoto Prize citation doesn’t list 4′ 33″. But a group putting on a concert in nearby Nagoya in conjunction with the prize ceremony asked Cage to perform his most famous work as part of the festivities. Evidently they were not familiar with Cage’s long-standing unwillingness to perform 4′ 33″. As Cage tells it, “I said, I don’t want to do the silent piece, because I thought that silence had changed from what it was, and I wanted to indicate that.” So instead he created a new silent piece: One3.

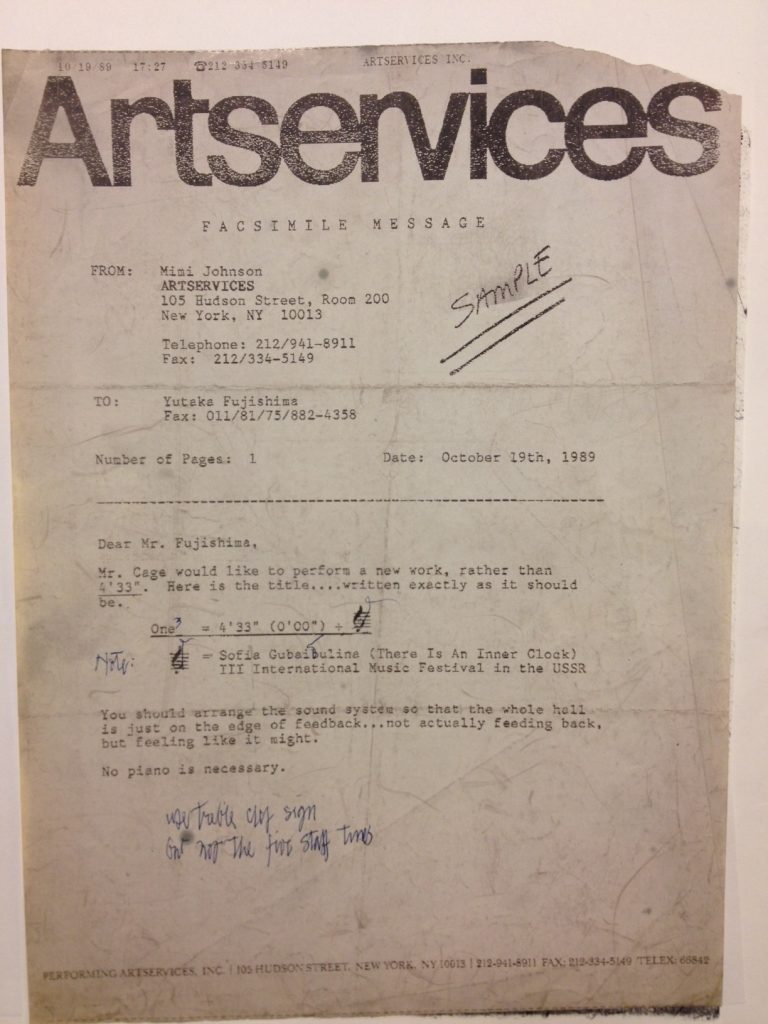

The instructions for the piece were sent via fax (reproduced above) by Cage’s agent Mimi Johnson to Yutaka Fujishima, who was arranging the concert. It gave the unusual full title of the piece:

Dear Mr. Fujishima,

Mr. Cage would like to perform a new work, rather than 4′ 33″. Here is the title … written exactly as it should be.

One3 = 4′ 33″ (0′ 00″) + 𝄞

Each of the components of the complex title tells us something about the nature of the piece. The first part—One3— places this work in the series known today as “the number pieces.” These are compositions Cage wrote in the last years of his life for various ensembles whose titles are just the number of performers: all the solos are titled One, the duos are Two, the trios are Three, and so on, with orchestra pieces having titles such as 103 and 108. When multiple pieces use the same number of performers, Cage uses superscripted numbers to differentiate them. Four (1989), Four2 (1990), and Four3 (1991) are all quartets, for example. One3, therefore, was the third solo piece in the series. It is an unusual “number piece” in that it does not use the same simple notation that is shared by almost all of the others: single notes or short phrases placed with flexible timing (“time brackets”). The series was still new in 1989, however, and the standard format for the pieces was still emerging.

The next parts of the title make explicit connections of this to the other silent pieces: One3 = 4′ 33″ (0′ 00″). One3 was meant to be a replacement on the program for 4′ 33″: a new and different silent piece to match the new and different silence of 1989. While his Japanese hosts wanted him to recreate 4′ 33″, Cage did not want to pretend to live in the 1950s. Silence—”the silent piece,” as understood in a general sense—was still at the core of his work, but the 1952 representation of that was no longer an option for him. And not even the new-and-improved 4′ 33″ No. 2 was right for 1989. One3 would represent the next step in Cage’s exploration of silence.

The fax contains the closest thing to a score for the piece, a description of how to arrange the sound system in the concert hall:

You should arrange the sound system so that the whole hall is just on the edge of feedback … not actually feeding back, but feeling like it might.

No piano is necessary.

Like 4′ 33″, there would be no intentional sound created in the performance, and like 0′ 00″, it would involved amplification. But in One3 there would be no action at all—just the space amplified to near-feedback level.

The final element in the title is the treble clef sign: One3 = 4′ 33″ (0′ 00″) + 𝄞. The original fax includes a note: “𝄞 = Sofia Gubaidulina (There Is An Inner Clock).” Cage and composer Sofia Gubaidulina met in 1988 at the Third International Music Festival in Leningrad. At the festival, she made a comment to Cage about his work that stirred his imagination. In a 1990 interview with William Fetterman about the origin of the piece, Cage explained: “In Leningrad, Sofia Gubaidulina had said that she liked my music but she didn’t like the watches, and I should remember that there was an ‘inner-clock.’”

This was the source of Cage’s idea for his role as performer of the piece: indicating the start and end of the amplified silence in a totally subjective way—following his own “inner clock”. This is not explained in the Artservices fax, but Cage described the performance in a letter to pianist Werner Bartschi:

What happens is that when it begins I am on stage or in front of the audience which is then brought to feedback level (not actual feedback but very near it), someone controlling the situation; I then sit in the audience for an indeterminate length of time (in Japan it was about 12½ minutes) not measuring it and then I return to stage + bow and leave, the feedback stops when I return to stage.

The Leningrad festival organizers used the treble clef as a symbol for the festival, and so Cage included it in the title. He liked the idea also that this clef was a “G” that could stand for “Gubaidulina” (or, as he joked with Fetterman, “it could be called Gorbachev, or glasnost”).

All these elements of the title work together, as Cage summarized them to Fetterman (while drawing them for him):

And this [the time] is 4′ 33″. 0′ 00″ is the obligation to other people, doing something for them. And this [the treble clef] is using an inner-clock. The thing I was doing for them was showing that the world is in a bad situation, and largely through the way we misuse technology.

One3 confounds our expectations of Cage much like Silent prayer does. Amplifying the concert hall space in this way is indeed a frightening experience—for all involved. The sound engineer must monitor the levels carefully to keep the amplification as high as possible but without tipping forward into feedback. This goes against some of her most basic training. And the performer must somehow stay unselfconscious and attuned to his inner clock as he sits in the audience, aware of his responsibility as a living timepiece. As a member of the audience, though, it is easy for me to whistle past the graveyard and say to myself: “ah, yes, it is another demonstration of Cage’s impossible silence, an opportunity to enjoy the subtle differences of the amplified ambient noise.”

It would be wrong to think in this manner—turning fear into an aesthetic acoustic experience—however “Cagean” it seems. As he explained to Fetterman, Cage wanted the audience to be disturbed. Indeed, he saw One3 as a gift to his audience, an experience that would point out what he saw as the perilous state of the world. It surprises us to find Cage delivering a message through one of his compositions, and it is deeply unsettling to hear how pessimistic that message is:

We are no longer certain that there will be any silence. We are no longer certain that there will be a world. It’s a very serious situation, and the news is, as you know, absolutely incredible.

When I first heard about One3, I thought of it as a more advanced version of both earlier silent pieces. 0′ 00″ had transcended the material silence of 4′ 33″, and now this new piece transcended even the notion of a performer or of any action at all. I saw it as the work of a wise elder who had devoted his life to a discipline of self-negation, someone who could at this point freely walk away and let the silence speak for itself, untimed, totally empty of all action. I was completely wrong, however. Instead, One3 is an example of Cage’s darker side (the other work that immediately comes to mind is his 1976 Lecture on the weather). Cage never identifies exactly what “very serious situation” he was concerned about, but certainly there was much concern about nuclear proliferation in the 1980s. Thinking back to the start of this series, perhaps my friend was onto something with his view that 4′ 33″ was about the atomic bomb, after all.

§ § §

There is a postscript to this story, one last silent piece after One3. Cage may not have been willing to perform 4′ 33″ at the request of the concert organizers in Nagoya, but shortly afterwards, he arranged a performance of an unnamed, unwritten version of his notorious silent piece. In 1990, Cage worked with the Scottish folk group The Whistlebinkies on a new piece, Scottish circus. They premiered this at the Musica Nova festival that year in Glasgow. At the same festival, they also performed “a newly devised version” of 4′ 33″. It is not clear whose idea it was to put 4′ 33″ on the program, but the version presented is different from any of the known scores.

The 1990 Glasgow performance was of the three-part 4′ 33″, but done as an ensemble of solos: each performer would perform it simultaneously with the others, but independently of them. As Cage described it:

In their performance of 4′ 33″, I wanted to show that a group is not one thing. I asked them to do it as seven individuals. The directions I gave them were that the silences should be between 33″ and 2′ 40″, but should be measured by an ‘inner clock’: this is apt to be slower that a real clock …”

The seven performers started 4′ 33″ at different times, and as each performer finished, they got up and left their chair. The performance was the subject of a bemused BBC Scotland television report.

I think of this new (third? fourth?) version of 4′ 33″ as the real silent “number piece”: the silent piece that acts most like the other number pieces. It uses the idea of an ensemble as a group of individuals and it has the technique of flexible timing. Instead of explicit time bracket notation, however, this flexible timing is produced by the inner clock (and I wonder where Cage might have taken this approach in other time bracket pieces, had he lived longer). Instead of single pitches or short phrases, the fragments of this new 4′ 33″ are silent, empty of intentional sound. The Whistlebinkies’ version of 4′ 33″ never got a formal name or score, so it’s hard to say whether Cage thought of this as a separate piece or as just another way of playing 4′ 33″. Looking at his open, gentle face in the BBC video, it is hard to imagine that this is the same composer behind the apocalyptic One3. Perhaps it is easier for us to end the story this way, to imagine this as Cage’s final, sunnier take on the silent piece.

Next in this series: One silent piece or four?

Home page for the entire series: John Cage’s silent piece(s)

Notes & asides

All the information about John Cage’s Kyoto Prize of 1989, including the official citation, is available on their website. Most of what we know about One3 comes from William Fetterman’s chapter on it in his book John Cage’s theatre pieces (Routledge, 1996). Much of that chapter is based on an interview that Fetterman did with Cage on 10 August 1990. Mr. Fetterman has contacted me since I published this post to clarify that the “very serious situation” that Cage mentions was global warming/climate change. The description in the letter to Werner Bartschi (24 January 1990) is published in The selected letters of John Cage (Wesleyan University Press, 2016). Thanks to Laura Kuhn of the John Cage Trust for the scan of the original fax score of One3.

The Whistlebinkies’ performance of 4′ 33″ came to my attention thanks to Glasgow filmmaker Wendy Kirkup. It is described by Whistlebinkies flutist Eddie McGuire in his article “A chance meeting: Cage and The Whistlebinkies” (A Scottish musical miscellany, Winter 2011).

Pingback: The silent piece, from stopwatch to inner clock - The piano in my life