During the pandemic, I had the opportunity to write about John Cage’s Cheap imitation for piano. This is one of my favorite Cage pieces, so I was happy to take on the assignment, even though I’d already written about Cheap imitation on multiple occasions. I chose it to open the last chapter of my book on Cage. I wrote about it for a recording of the violin transcription. I wrote about it on two different occasions for this blog. I wrote about it when the New World Symphony performed the orchestra version for the Cage centenary.

On all of these occasions, I told the same basic story, a love story between John Cage and the music of Erik Satie. One of the things that attracts me to Cheap imitation is the way that it breaks through the strict views that Cage had about music in the 1950s and 60s: that music should be always looking forward, using new ideas; that it should reject the personal; that it should embrace the electric, the technological; that it should include everything, aspiring to encompass the entire universe of sound. Cage did not always actually live and compose in complete accordance with these views, but he loved to speak and write about them. Cheap imitation, born of his devotion to Satie, didn’t so much blow up those views as it flowed like water around them.

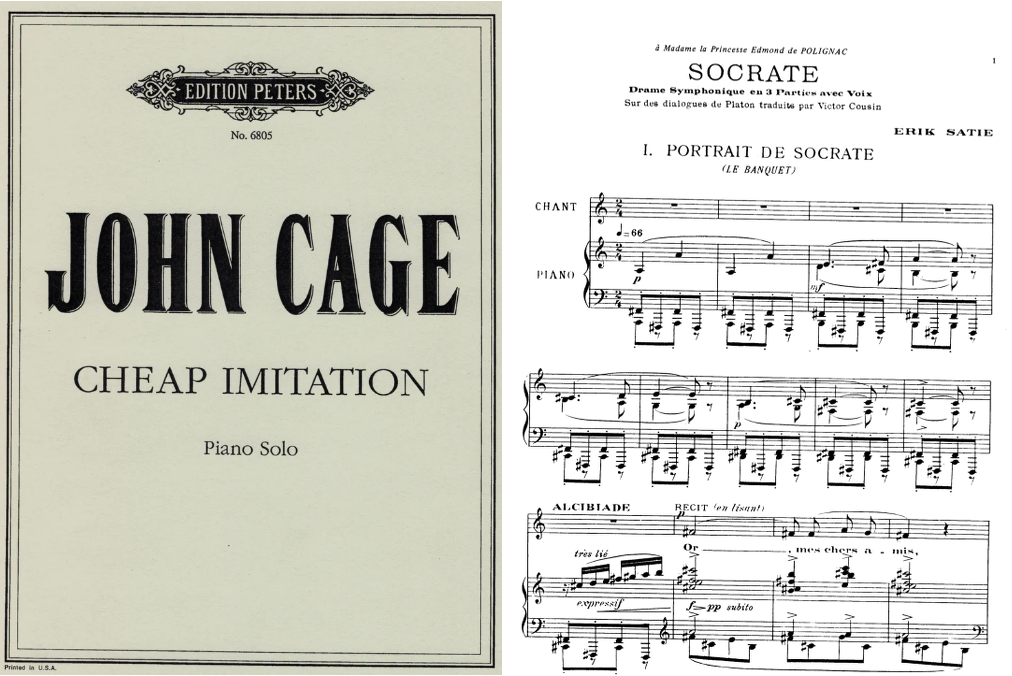

As a pianist, I’ve also played Cheap imitation, although only for my own delight, never in public. For the recent writing assignment, I decided to mix business and pleasure and play through the piece again at the piano. Cheap imitation is based on Erik Satie’s Socrate for voice and orchestra. I hadn’t heard Socrate in a long time, so I downloaded the piano-vocal score and started playing through that, too. I’d play a bit of the Satie and then play a bit of the Cage imitation, back and forth, letting the two pieces mingle in my fingers and mind.

As I was doing this, I started noticing things and asking questions. It occurred to me that I had never actually worked out the details of how Cage composed the piece. I’ve summarized the method very vaguely in a few sentences, but I’ve never actually dug into it, not the way I did for the chance pieces of the 1950s. Frankly, I just assumed it was pretty simple—trivial, really. But playing it and comparing it to the Satie score started to get me thinking. I sensed something more complex here.

Back in the 1980s, when I was in my twenties, I had rigorously examined Cage’s scores and notes from the 1950s. I made all kinds of observations, measurements, analyses, and experiments to infer the processes he used to compose his first works using chance. When I was in my thirties and beyond, I moved on from this kind of work, and so I breezed right by the composition of Cheap imitation.

Playing through it at the piano, here I was, in my sixties, suddenly getting the urge to go back to pick up the tools of my earlier life and dissect this piece to expose its inner anatomy. I wanted to understand the technicalities of Cheap imitation, even as I wanted to preserve its messy humanity. Perhaps the perspective of age opens up the possibility of an understanding of things in multiple dimensions. Perhaps like Cage in the 1970s, I was less attached to the flatness of one view or another.

So I spent time pursuing this investigation of Cheap imitation, which I’ll recount here. First I took a look at exactly what Cage said about the method he used to compose it. I had skimmed it before, but this time I looked more closely and critically at it. I then followed the system Cage described as it operated in the piece itself. I compared Socrate and Cheap imitation: did the method really work the way Cage said it did? What I found is that there’s a little more to it than Cage’s brief description suggests.

Then I took up the question of what was outside the system. Where did Cage have to make personal choices? How did those choices create the style of the finished work? And then I started asking questions about why those choices were made. This brought me back to Satie’s Socrate and to Merce Cunningham’s parallel journey in his dance Second hand.

I spent a good deal of time immersed in the notes of Satie and Cage’s music. Much of what I’ll present here is pretty technical. But what I hope is that this will be more than just a documentation of how Cage composed Cheap imitation (although that’s certainly worth knowing). I want to use Cheap imitation as a way of demonstrating how I go about engaging deeply with a piece like this. It’s a combination of technical analysis, musical feeling, and psychological intuition about John Cage.

This is part of the series Understanding Cheap imitation