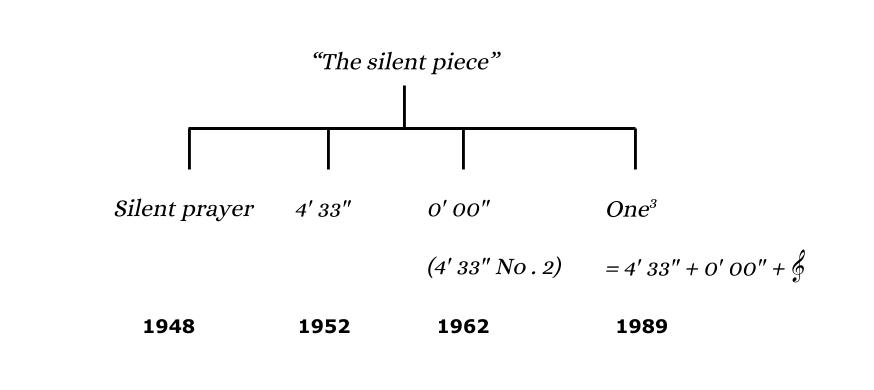

I have now presented the history of each of the four different compositions by John Cage that he himself described as silent in some way. He also spoke of his “silent piece” as a single thing, which raises the question of which of these four works he meant. Was it always 4′ 33″? Or did he mean all four of them to be taken as examples of a single musical idea? Silent prayer, 4′ 33″, 0′ 00″, One3: are these evolving manifestations of the same work, or are they four distinctly different works? Should we speak of John Cage’s silent piece, or John Cage’s silent pieces?

If we start from Cage’s statements about “the silent piece,” we could get the impression that for him there was a single conception of a work of music made entirely from silence. His comments appear in interviews in response to questions about 4′ 33″. He described it as “my own best piece, at least the one I like the most”, and that “I always think of it before I write the next piece.” When I look at the context of these statements, and when I look at them as a whole, it seems clear to me that Cage is using 4′ 33″ as a symbol for something bigger than any single composition. The “silent piece” is a way to refer to a guiding principle in his life and work, one that he found most people just did not comprehend. In conversation with William Duckworth, he described it as “the highest form of work”, and attributed to it great power: “It opens you up to any possibility only when nothing is taken as the basis. But most people don’t understand that, as far as I can tell.” Cage then portrays it as a kind of meditation practice, although he never uses that word:

JC: Well, I use it constantly in my life experience. No day goes by without my making use of that piece in my life and in my work. I listen to it every day. Yes I do.

WD: Can you give me an example?

JC: I don’t sit down to do it; I turn my attention toward it. I realize that it’s going on continuously. So, more and more, my attention, as now, is on it. More than anything else, it’s the source of my enjoyment of life.

Clearly in this exchange with Duckworth Cage has gone far beyond 4′ 33″ as we know it from 1952. While we could then associate this “silent piece” with a single composition that embraces all the specific silent pieces, I am more inclined to describe what Cage is referring to as silence itself. “The silent piece” represented Cage’s deeper understanding of emptiness, of silence in a spiritual sense. Cage understood silence as the freedom from identification with self or ego: moments when he could forget himself, enraptured, and thus gain himself (to paraphrase “A composer’s confessions”). Through his work with chance, Cage was able to let go and touch this emptiness, this compositional silence. He then referred to this musical experience of emptiness as “the silent piece”.

The common factor here, from 1948 until his death in 1992, was this spiritual dimension of silence as the motivation behind all the compositions made of silence. One3 is remarkably similar in this regard to Silent prayer, even though half of Cage’s life separates the two pieces. Both were explicitly presented as warnings about the dangers of technology: in 1948, the dangers of ubiquitous Muzak, and in 1989, the unnamed “bad situation” humanity was in. And both works present silence—the sacred pause—as a means of recognizing the situation. Silence here is an act of resistance and consciousness-raising. 0′ 00″, with its injunction to act in a way that is free from ego and self-consciousness, and to recognize one’s obligations to others, is likewise at heart a spiritual work. It invites the performer (and the performer was most often Cage himself) to go beyond self and just be nobody in particular.

4′ 33″ is the odd piece out in this group of silent pieces. It lacks any overt spiritual point of reference, any sense of a turning inwards. Instead, it appears on stage as a material thing, a piece of music made from silence. A performer sits there, turning the pages of the score and measuring the time with a stopwatch. It has always been a problematic piece for me for just this reason (and I think it was for Cage as well). For me it carries with it the air of the fetish, a totem that supposedly carries the powers of silence, but which for the unbeliever is just a mere object. The endless analysis and performance of 4′ 33″ just amplify this problem.

§ § §

All four of these compositions made out of silence share this common spiritual heritage, but at the same time they are very much individuals. Each is shaped by the personal, intellectual, and cultural conditions in Cage’s life at the times that they were written; each takes advantage of the compositional apparatus available to him. Silent prayer is the fruit of Cage’s engagement with the writings of Ananda Coomaraswamy and the gap he saw between the spiritual purpose of art and its commodification in contemporary culture (as represented by Muzak). Silence was a strategy to resist the ego-driven culture of musical composition, and Cage’s duration structure was the technique needed to define that silence.

Ultimately, Cage discovered that using chance operations in his composing was the way to achieve this emptiness, this silence. This insight, when coupled with his experience in the anechoic chamber, led him to redefine silence as unintended sound. The stage was set for 4′ 33″, the concert piece in which the performer sits silently in front of a blank score. Taken together with Rauschenberg’s white paintings, it is a creation of its time. Like the white paintings, it is a bit of a dead end: a work that had to be made, but was not to be dwelt upon.

In the 1960s, Cage was always on the road and always being asked to perform. He probably was often asked to perform 4′ 33″, but he was well aware of the problems of that work. In response he wrote 0′ 00″, which was 4′ 33″ No. 2. It was the perfect piece for his touring lifestyle, needing only something ordinary to do and the means to amplify it. It took the focus away from “John Cage, composer” and put it more fully on the awareness of the everyday. And this pattern of creating a new silence rather than repeat the silence of 4′ 33″ continued decades later, in 1989, when he amplified empty space itself in One3. This was a response to the growing sense of environmental danger at that time. Cage pared more away from the basic idea of the silent composition: no more stopwatches, no more action.

Is there one silent piece or are there four silent pieces? The answer is that it is a bit of both. These four compositions—Silent prayer, 4′ 33″, 0′ 00″, and One3—all stem from a single conception of silence, but each meets that conception at a different point in time with different conditions, possibilities, and needs. We benefit from considering them in relationship to one another, rather than separately. They all talk to one another, inform one another, reveal one another. And we certainly can no longer think of 4′ 33″ as John Cage’s ultimate statement on silence and stop there. It is wrong to let our discussions and understandings of Cage’s silence be bounded by the limitations of 4′ 33″. Instead, we need to embrace all four of the silent pieces, to go beyond measuring silence with a stopwatch in Woodstock and become more familiar with the composer seeking a sacred pause, the non-performing performer doing their work, the threatening amplified silence of our current world.

Home page for the entire series: John Cage’s silent piece(s)

Notes & asides

I’m struck by the way that all four silent pieces have, to some degree and in some way, been failures. Silent prayer was never even created, much less sold to Muzak. Cage’s ambivalence and alienation from 4′ 33″ was the subject of the fifth installment of this series. 0′ 00″ has been largely ignored in favor of 4′ 33″, and One3 is unpublished and almost completely unknown.

For myself, I think we would all do well to put 4′ 33″ aside for a time and take up Cage’s lesser-known silent compositions. One3 and its message of imminent danger to the planet from the misuse of technology seems particularly appropriate for our times. I’m not certain whether Cage, working in 1989, was specifically thinking of climate change (it was just beginning to become a prominent issue at that time), but filling normally complacent concert halls with the unsettling amplified silence of Cage’s last silent piece would be a perfect anthem for the movement to wake the world up to its dangers.

The interview with William Duckworth appeared in his book Talking Music: conversations with John Cage, Philip Glass, Laurie Anderson, and five generations of American experimental composers (Schirmer Books, 1995).

Pingback: John Cage's silent piece(s): Silence changed: One3 - James Pritchett