So how, exactly, did John Cage write 4′ 33″? This may seem like a silly question. Indeed, all the stories of it as a joke, a hoax, and a fraud are based on the idea that no effort was required to compose it. But for Cage in 1952, compositional silence was critical: he had to have a way to compose that came not from his personal desires, feelings, or thoughts, but was instead grounded in a discipline that created emptiness. In 1951 he had committed himself to using chance operations in his composition, and so 4′ 33″, even made of silence as it is, must have been composed using some kind of process involving chance, most likely the I ching, the Chinese oracle book.

In 1988, in a question-and-answer session during Cage’s lectures at Harvard, he gave one description of how he composed 4′ 33″:

In the case of 4′ 33″ I actually used the same method of working [as Music of changes], and I built up the silence of each movement, and the three movements add up to 4′ 33″. I built each movement up by means of short silences put together. It seems idiotic, but that’s what I did. I didn’t have to bother with the pitch tables or the amplitude tables, all I had to do was work with the durations. … It took several days to write and it took me several years to come to the decision to make it.

What Cage remembered, then, was that he used the same system as Music of changes, this time for silences only. If we take him at his word, this would mean that the piece started with a duration structure. This structure was presumably in three parts, since the piece consists of three movements. Each of these large parts would be subdivided into a number of phrases, the exact number and lengths of phrases for each movement determined by the structure proportions. If he followed the model of Music of changes, these phrases would consist of measures of 4/4 meter. For each phrase, he would use the I ching to select from a chart of metronome markings to select a tempo. The tempo of the piece would thus continuously speed up and slow down from one phrase to the next. Then he would use the I ching to select from a chart of durations to determine the precise rhythm of rests for each phrase. He would repeat that process until the entire phrase structure of the piece was complete. The final duration of the piece—four minutes and thirty-three seconds—would only be known after the process had determined the tempi for the different phrases.

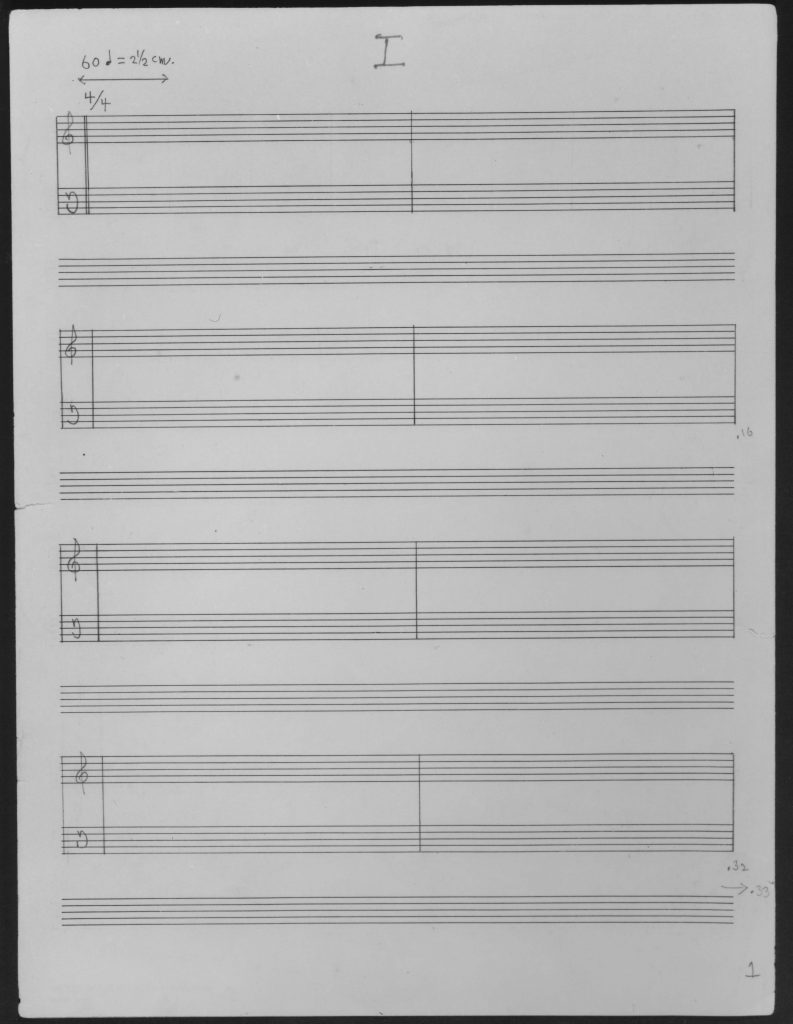

This speculation about the piece lines up with David Tudor’s account. According to Tudor, in 1952 he was given a traditionally-notated score of the piece. This score does not survive, but Tudor made a replica of it from memory in 1989, shown in the photo above. Tudor’s recreated original score consists of blank measures of 4/4 meter at a tempo of 60 = quarter-note (i.e., one second per beat). Except for the constant tempo, this is exactly like the score for Music of changes. We have neither the original score to confirm Tudor’s account (and on another occasion he recreated the score slightly differently, without the 4/4 meter), nor any notes or sketches to confirm Cage’s. However, the result of a compositional process suggested by Cage’s comments at Harvard would look very close to Tudor’s recreation.

A short while after the Harvard lecture, Cage described the composition of 4′ 33″ somewhat differently in an interview with William Fetterman. Here, he said that he used a deck of cards to keep track of the durations:

I wrote it note by note, just like the Music of Changes. That’s how I knew how long it was, when I added all the notes up.

It was done just like a piece of music, except there were no sounds—but there were durations. It was dealing these cards—shuffling them, on which there were durations, and then dealing them—and using the Tarot to know how to use them. The card-spread was a complicated one, something big.

[Question: Why did you use the Tarot rather than the I Ching?]

Probably to balance the East with the West. I didn’t use the [actual] Tarot cards, I was just using those ideas; and I was using the Tarot because it was western, it was the most well-known chance thing known in the West of that oracular nature.

This description suggests that there was no rhythmic structure to 4′ 33″, but instead Cage used some means (perhaps the I ching) to determine how many silent durations would be in each movement. He then selected the specific durations by shuffling and dealing the cards.

At first encounter, this seems improbable: it is so unlike Cage’s other working methods. But there are aspects of Cage’s compositional techniques in 1952 that connect to this story. Cage did use a deck of cards in the creation of at least one composition: Williams mix, also composed in 1952. This work for magnetic tape involved charts of sounds, just like Music of changes, but with many more charts and hence many more sounds to manage as they moved into and out of the charts. Cage put each sound on a card and used a deck of these to select which sounds would be added to the charts. Cage’s notes describe a somewhat elaborate system for controlling the content of the deck, but no mention of the Tarot or any particular way of dealing the cards.

Then there is the matter of the structure of the piece, which the Tarot-dealing method suggests would be simplified from Cage’s other compositions of the time. Again, there is a precedent for this in Cage’s work of the early 1950s, when he experimented with simplifications of the structure. Imaginary landscape No. 5 and Waiting both use a different way of relating proportions at the small and large scales. Water music applies the proportions directly to clock time rather than metrical time. In all three cases, there are no tempo changes.

So a method for creating 4′ 33″ that involved cards and a simplified structure is certainly possible: Cage was trying out different methods of composition at this time. Without discovering some kind of original score and working notes, though, we will never have a definitive answer to the question of how Cage actually composed 4′ 33″. However it was done, what we know is that it was composed as a piece in three sections, it was performed by David Tudor in Woodstock in August 1952, and it then triggered a reaction that has echoed throughout the years since then. It may have been difficult for Cage to finally write his silent piece, but responding to the way it was received may have been even more challenging. Cage’s own attitudes towards 4′ 33″ will be the subject of the next installment of this story.

Next in this series: Did John Cage regret writing 4′ 33″?

Home page for the entire series: John Cage’s silent piece(s)

Notes & asides

I have tried here to push the usual explanations just a step or two further, to imagine exactly what steps Cage took in composing 4′ 33″. I had hoped to find a single answer that would make sense, but, sadly, there are many possibilities here. For a long time I dismissed the Tarot card story, but while working on this series I found that the more I dug into it, the more possible it seemed. Until we find a paper trail of some kind, we will just never know. There are many pages of I ching hexagram numbers and calculations that Cage made when composing pieces in the 1950s. It is tantalizing to think that among these may be the working notes for 4′ 33″, yet unrecognized.

Pingback: John Cage's silent piece(s): The origin of 4' 33" - James Pritchett